Kia ora, we’re heading into Whiringa-a-Rangi (November) and weekly roundup’s back with a weekend’s worth of stories for you.

Header image: the world’s longest train, via Twitter.

The week in Greater Auckland

Monday’s post was a guest post by Aaron Schiff about changes in Auckland’s young(ish) adult population over time.

On Tuesday, Matt wrote about AT’s plan to reduce services in order to make bus timetables more reliable.

On Wednesday, we had a guest post by Simon Lyall which explored what a minimum, low-cost light rail project could look like.

Yesterday, Jolisa celebrated the dozens of kids and parents who turned up for Kidical Mass last weekend, and generally had a blast cycling into and through the city together.

Wheels of change around Tāmaki Makaurau

A few weeks in to Wayne Brown’s tenure and many of us are on tenterhooks waiting to find out what the new mayor, council and local boards mean for transport in the city. We hear that work’s still happening on the New North Road Connected Communities design, even though planned community engagement events were postponed last week.

Reaching out to the mayor

Auckland Central MP Chlöe Swarbrick met with the mayor a week or so ago, and since then her glorious green poster campaign has appeared on the City Centre’s streets.

The posters cover five themes, greater environmental protection for the Hauraki Gulf, pedestrianise Queen Street, “fix” nightlife by investing in audience-attracting culture, improve housing affordability by building inside the existing urban area and a call to invest in public transport, walking and cycling.

“The key thing is to get on with the (council’s) City Centre Master plan which would have a massive benefit to the 45,000 residents living there,” said Swarbrick.

Women in Urbanism issued a powerful open letter to the Mayor this week, urging him to keep going with the Great North Road, Pt Chevelier, Grey Lynn and Westmere improvements and cycling projects.

These projects have been six years in the making. In that time, repeated consultations on all three projects have confirmed strong and growing support across the board. Two thirds of submitters support the Grey Lynn design, with calls to get on with it. The most supported features in the Pt Chevalier consultations were cycling improvements (outstripping opposition by 10:1), pedestrian safety and bus lanes. For Great North Road, people who drive were the largest group of commenters, and still the most popular design elements were continuous safe cycleways, pedestrian safety, and bus lanes.

A slight diversion

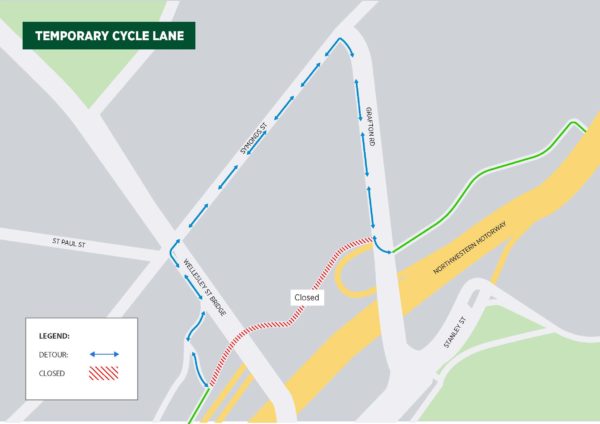

A section of the Grafton Gully shared path between Grafton Rd and Wellesley St will be closed for the next few months while Vector works on a second power connection for the hospital.

In response, a section of Symonds St has been turned into a temporary cycle lane – and we think AT has done a good job with this one. Let’s make it permanent (and turn the traffic lane into a bus-only lane!)

Barriers and cones are going down for the temporary cycleway on Symonds St while works are undertaken on Grafton Gully cycleway. pic.twitter.com/VJDYOhKtbd

— Shaun Baker (@sbaker1428) November 1, 2022

A whole lot of love for rail

If you’re signed up to Auckland Light Rail’s newsletter you will have seen the results of a trip to Dublin to chat to passengers of the Luas, Dublin’s surface light rail system. (NB we don’t know if ALR people actually went to Dublin, or if the video was produced by people on the ground there.)

The Luas has fast become the backbone of Dublin’s public transport network. Check out the video to hear from a couple who got rid of a car after getting a Luas stop in their neighbourhood, a teacher who loves how quiet the surface-level trains are, and a young woman in a wheelchair who gets to go places with her friends thanks to the Luas.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q78AGUUl2kw

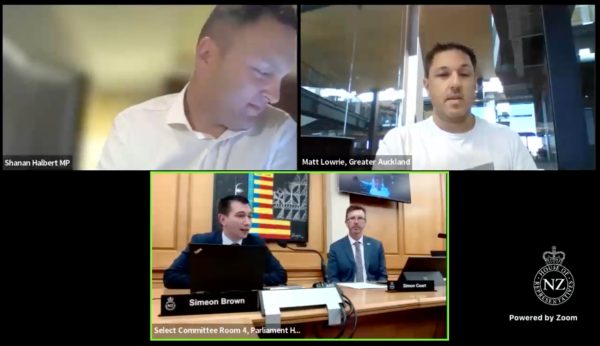

Greater Auckland’s say on the future of inter-regional rail

Matt got a chance to represent Greater Auckland’s views on inter-regional rail at the committee’s hearings last week. You can watch a video of the hearings on the Transport and Infrastructure Committee facebook page. Matt’s presentation was last, so skip along to 3:00:00 if you’d like to go straight there.

And as a final aside – we keep seeing interesting and encouraging stories about outcomes of Germany’s summertime 9 euro transport ticket. This latest study found that the cheap ticket helped low-income families feel more connected to their communities.

For many respondents, the ticket enables access to mobility offers that they were previously unable to use or only to a very limited extent. The survey confirmed that the majority of those surveyed traveled more frequently while they were in possession of the ticket.

(Quote translated from German.)

A study has shown that Germany's €9 ticket massively increased low income households' social participation, thereby boasting their overall quality of life and alleviating feelings of loneliness https://t.co/Iq6qp8NWg6

— Jessica Bateman (@jessicabateman) October 25, 2022

Checking in on George St

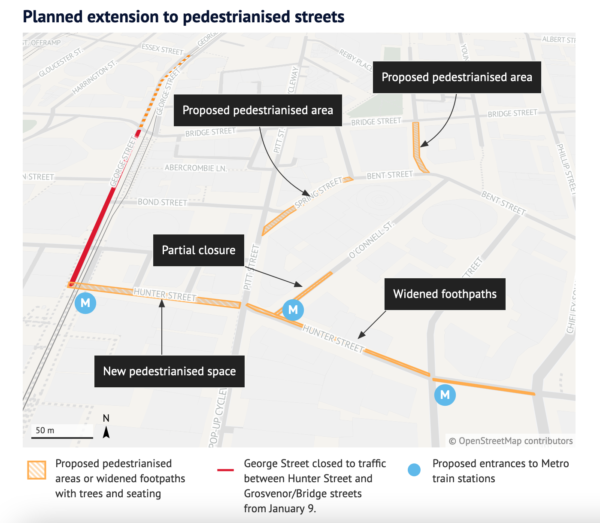

George St, in Sydney, has turned up on Weekly Roundup in the past. It was Sydney’s original high street, and is still a busy shopping street in the city centre. Over the last half decade, several blocks of the street have been turned into a light-rail transit street. This section has been pedestrianised (apart from the trams), and improved with new paving and landscaping.

People love it, and the street is even busier now.

https://twitter.com/trashyhonky/status/1587695249156997121?s=46&t=AyjumaIgn26sZgTIwnfAbg

So what’s next for George Street? Looks like the street has become a trendsetter in Sydney’s downtown: building off its success, and a future metro station, the City of Sydney is planning to pedestrianise several other streets in the area. What this looks like is a growing network of spaces where pedestrians are genuinely prioritised.

The proposed pedestrianised areas include the northern portion of George Street, which you can see in the top-left corner of that map. The success of the current project has enabled conversations about reclaiming much more street space for people.

“George Street’s transformation from a traffic clogged arterial route to a destination in its own right is nothing short of remarkable,” the Lord Mayor said.

“We know our community wants the outstanding public spaces that projects like this achieve and I am incredibly proud to be overseeing this transformation, which, once finished, will have reclaimed more than 20,000 square metres of former roadway between Central and Circular Quay.

Tangentially related, in that it mentions projects like the metro station underneath some of those future pedestrianisations, is this critique of New South Wales’ ‘over-designed mega projects’ by Australia’s infrastructure minister Rob Stokes. Stokes argues that ‘compliance culture’ is leading to projects being over engineered, thus requiring unnecessary amounts of concrete and steel, hindering the Australian construction industry’s efforts to reach net zero.

“There is an irony here. Because we’ve got very conservative design standards we’re actually putting more concrete and steel into roads and bridges and railways than anyone else in the world.”

Stokes pointed to the recent construction of the multibillion-dollar Metro rail lines as an example of a project that could have used less material without impacting design integrity.

Taking over the world, one bicycle at a time

While we’re wary of contributing to discourse that suggests there’s a culture war between people who ride bikes and people who drive cars, there’s no denying that cyclists and associated infrastructure are targets for some pretty intense reactions. Writing on Streetsblog NYC, PhD candidate Nadia Williams writes about her research into bikelash, and why it happens.

Cyclists, by existing, want to exercise a right to the same space we all tend to see as drivers’ rightful property. When sharing a lane, they are seen as “in the way,” robbing drivers of priority. When cycle lanes are installed, cyclists are seen to take away some of drivers’ goods.

One way to get rid of bikelash is to simply legislate it away. Bruges is the latest European city making changes to city streets so they’re easier to get around by bike. A an area of the city that includes 90 different streets has been turned into a cycling zone, which has two key rules: all streets have a 30km/hr speed limit, and cars are not allowed to overtake cyclists. It’s a quick, cheap and easy way to make streets safer for people on bikes.

This way of making bike-friendly streets has been gaining traction in Europe for some time now, with many countries opting for the model as a quick and easy alternative to making dedicated cycling lanes. In Bruges, the only thing local authorities needed to do is change signage and road markings.

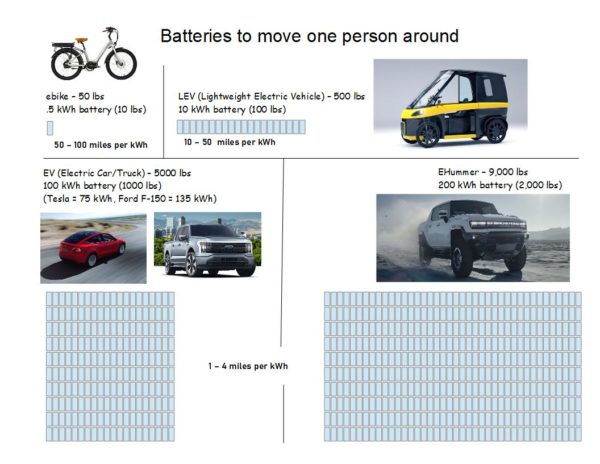

What does a bike look like, in batteries? It looks a heck of a lot smarter than an EHummer.

Bike libraries are a wonderful, community-based version of bikeshare programmes that provide access to an ebike free of charge. These initiatives are popping up across the USA. It’s a brilliant way of breaking down a whole lot of normal barriers: all you need to rent a bike is your library card.

Instead of requiring the use of a credit card or a smartphone to unlock an electric-assist bike from one of the city’s more than 50 docking stations, Community Pass users check out an access fob from the library instead. The fob passes can be checked out for up to a week at a time. Each of the city’s nine public libraries have two passes available. So far this season, from March 15 until the end of last month, the city’s libraries have seen 279 fob check outs.

Private businesses can have a huge impact on their employees travel choices, and more companies are using transport carrots and sticks to encourage sustainable modes.

In many cases, these changes aren’t being foisted on an unwilling workforce. According to a Deloitte report, two-thirds of organizations feel pressured by their employees to implement more policies that counteract climate change. An IBM survey revealed that 69 percent of the 14,000 workers polled were more likely to accept a job with an organization they consider to be environmentally sustainable — and to stay there.

What do Aucklanders who ride want? More bike lanes!

A quick unbiased vox pops with regular everyday Aucklanders on their way to work this morning. cc @BikeAKL @CriticalMassAKL pic.twitter.com/FCiFJabxMc

— Ben Gracewood (@aotearoa_ben) October 24, 2022

Streets and their unrealised potential

This is a fascinating article from a few months back, over at The Guardian. What’s the best way to reduce traffic in urban areas? Based on a review of over 800 studies, and 10 years worth of data from European cities, the authors rank the 12 most effective strategies.

In the top three? They’re all about limiting cars’ access to streets: congestion charging, parking restrictions, and limited traffic zones.

And ultimately, it’s a suite of policies working together that has the strongest impact.

Narrow policies do not seem to be effective – there is no “silver bullet” solution. The most successful cities typically combine a few different policy instruments, including both carrots that encourage more sustainable travel choices, and sticks that charge for, or restrict, driving and parking.

Putting parking to better use

Reclaiming car parking is one of the best opportunities we have for taking space back from cars (and it’s number 2 on the list above.) The trend of abolishing minimum car parking requirements is moving steadily across the USA, following in the footsteps of Aotearoa.

✅Cambridge, Massachusetts

✅Lexington, Kentucky

✅Culver City, CaliforniaAbolished minimum parking requirements THIS WEEK. pic.twitter.com/rjaUwQTxHe

— Jonathan Berk (@berkie1) October 28, 2022

The benefits of repurposing on-street car parking for more people friendly functions is being revealed as more places dive into the economic outcomes of their COVID-19 pandemic street projects. In Canada, where over a dozen cities have removed minimum parking requirements, a study of Toronto’s pandemic parklets and street dining found that the pop-up spaces earned nearly fifty times more than they did as parking spaces.

Researchers for an association of local business improvement areas estimated that customers spent $181-million in the repurposed parking spaces in the summer of 2021. The same spaces would have generated $3.7-million in parking revenue, according to the local parking authority, and even that modest figure assumed prepandemic levels of demand.

Another study, by the New York City Department of Transportation, found that NYC’s open streets program had profound benefits for businesses.

“The Open Streets program has been an important tool to create more space for people on our streets and encourage activity in our communities,” said Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine. “As we work towards a full and strong economic recovery, we must continue to creatively activate our streetscapes in ways that support thriving, diverse neighborhoods.”

Wellington’s parklets are going strong, too. We hope we’ll see a few more of these appear in time for summer.

Picking up my locked & docked bike post gym and I thought WHY NOT enjoy a Swimsuit coffee in the sun and send my first few emails of the day from this ex-car park. Yes I’ll keep tweeting Dixon St appreciation @WgtnCC pic.twitter.com/PDtU4M3hyE

— Miriam Moore (@miriammooretoo) October 25, 2022

Odds and (b)ends

Walking is climate action! (Always has been.)

"You are helping by walking short distances." This was true in this historic New Zealand wartime poster. This is true in EVERY city, in EVERY nation, ALL the time. Great @victoriawalks find & share. #walkablecities pic.twitter.com/kAQby27It0

— Brent Toderian (@BrentToderian) October 25, 2022

Did you catch this world record attempt last week? How many engines do you think they needed to shunt it along?

https://twitter.com/flywheelmedia1/status/1586347505402322944

Wishing you long trains and even longer bike rides this weekend. Hei te Rāhina!

Processing...

Processing...

Germany has just agreed to re-instate the monthly ticket, this time for 49 Euros, but imagine being able to travel through the entire country (apart from fast intercity services) for NZD2.50/day

Just on batteries; a Penn State project has managed to enable long-life rapid charging of batteries from to 70% in around ten minutes using a physical component at the cell level.

https://www.greencarcongress.com/2022/11/20221103-psu.html

You can get away with much, much smaller batteries if you can recharge them quickly without fear of ruining them. Plug in, take a whizz, stretch your legs, come back to a decently charged vehicle. No 500 mile battery required.

Would need a pretty thick cable

Thicker than a fuel hose?

Yes these are quite thick and stiff cables. These cables carry hundreds of amperes so they need a very large conductor.

And those cables are already undersized for the amount of current they carry, and they have water cooling in them so they don’t get too hot due to the current.

Not much thicker than we already have on chargers that can give 300kw already, I’m guessing. You’d just be able to do it more often without buggering a smaller battery.

Smaller battery, smaller cars. Smaller cars = safer cars. And frankly, smaller, lighter cars = more fun cars. It’s win-win-win.

The ALR video of the Luas is super! Well done.

Note, it’s a line on the surface. And that’s a big part of why it works – why it’s so accessible, why the shots from within the vehicles showed people enjoying the view, why it has improved the streets.

And why it’s something they could afford.

+1000

Something like the Luas would fit quite nicely down Dominion Road… Just saying….

As evangelical pro-cycle and -pedestrian etc infrastrucurists, how do we know that our evangelism is the “right” one that will be proven to be correct in the long run? The car revolution post-WW2 promised to be the way of the future and obviously turned out to be terrible a few decades later. How do we know that pedestrianising CBDs for example will be good in the long run? I feel like it’s obvious that it just will be, but sometimes I fear that I am getting as caught up in ideology as the pro-car people were/are without considering unintended consequences down the line.

I think the easiest way to think about it is “How far has the pendulum swung?” and the answer to that is “It hasn’t really swung far – in fact, in some senses it’s still stuck”.

We are so far away from a “cycle and pedestrian-centric” transport environment in NZ, it feels a bit like worrying about how millionaires are going to be able to afford breakfast when their workers want a 2 dollar an hour raise.

More seriously, look at the facts of history. Walking – and to a historically shorter window – cycling, never had any real DOWNSIDES. There’ wasn’t ever a time a single city got “destroyed” or “made unliveable” or “made unpleasant” because it’s people walked and cycled. The “risks” of “going too far” are simply pretty much not there. Walking and cycling – and prioritising them – have their LIMITATIONS. But they certainly have pretty much no real societal risks. This is not a new technology / social movement like car-centric cities were in the 20th century. This is going back to something that worked well for humans for… uh, pretty much all recorded history.

“There’ wasn’t ever a time a single city got “destroyed” or “made unliveable” or “made unpleasant” because its people walked and cycled”

AGREE x 1,000

For the opposite scenario, see Houston in the late1970s. https://miro.medium.com/max/736/0*NL4kXJLGCu_Agaz1.

Cities were pedestrian-centred for almost all of humanity. Car-centricism emerged in the 1950s in an environment of nuclear families, cheap land, plentiful energy and few concerns about pollution. It was a very specific time but, due to path dependency we are still living with it.

It cannot last forever. In the future history of urban planning, car centricism will just be a blip.

Pedestrianisation tends to work best when there is a large inner city population. Some cities in the United States have reversed pedestrianisation because of high car dependency. Admittedly many businesses overestimate he proportion of their customers who arrive by car, but having a large constituency who support repurposing space is important.

Eh, you can pedestrianize smaller suburb centres, too. Takapuna, Birkenhead, Mt Eden, Onehunga, Ponsonby, … Good transport to central points in these suburbs, maybe even include some garages on the centre’s fringe, and pedestrianize the rest. Also more bike lanes so that children (and teachers!) can cycle to school…

But yes, building more sprawl and separate houses completely from shops rely fs walkability up.

Northcote has had a pedestrianized main street since 1959.

Yes, so it can be done in smaller centres than the CBD.

I would think that if you took away most of the parking in Onehunga (or other suburban centres), then most people would either walk/cycle/scoot/skate or take the bus to get there… those that don’t will go somewhere else, like they probably already do now

You could even pedestrianised centres out south such as Papakura, Manurewa and Papatoetoe. There is plenty of parking on the fringes of the main streets. Might revitalize some of these run down centres.

Interesting point and I have had the same thought; I am very much for active modes (including across the Waitematā harbour) and light rail.

But looking back at history and trying to learn from it; people ripping up tram lines, knocking down inner city ‘slums’ and building motorways. Or the grand visions building modern state of the art state housing in many countries that ended up with slums, where they have had to now knock down buildings and restart.

I am sure many of the project planners of the 50s,60s and 70s were well meaning and thought they were doing the right thing. They may have been hard on the environment, but glad right now that my grandparents did build out all that hydroelectric generation rather than build coal plants

The last couple of years have help prove that we really can’t predict the future well. Who knows how much impact the move to online buying (with in person shopping becoming a more recreational experience) and hybrid/flexible/WFH roles has on the job market. Things like EVs, self-driving vehicles or the ongoing impact of electric scooters & ebikes.

I think my frustration comes about in that infrastructure and transport is still stuck with long planning & build time frames. So for instance, light rail if they had just started by building some sections, even if not perfect or we decide later it should have been fully automated, we would have some light rail and a team of people who know what they are doing.

We don’t know the future, but I know we tend to overestimate change in the short term and underestimate long term change. All we can do it build what we think is best for the environment and society, and change as/when required.

My biggest issue is conservative viewpoints and ‘nobody wants X as everybody wants to drive as they do now’; Imagine Auckland in 50 years and noisy dangerous flying cars are all the rage and reshaping the city so that people migrate to what islands remain above water. Who know what that city looks, works like, but right now we have to provide options

I suppose, when weighing this up, you need to decide how much weight you put on a city that is pleasant and healthy to live in, where our children aren’t injured or stunted in their development, and on a planet that is liveable.

Clearly, it might be worth getting the scales out to weigh different scenarios against each other if those things are considered unimportant.

About time Sydney did something, I always found their city centre disappointing. They are an Auckland and Melbourne is a Wellington. Sydney and Auckland know they could be more like Melbourne and Wellington (with much better weather), but for some reason choose not to.

Probably because Wellington is an awful place.

We only tell people from Auckland that it is awful, to keep them away. Its actually pretty fantastic – but we don’t want all you lot to think that, or you might move down here and bugger it up.

Both Welly and Melbourne are great places to visit but I’d never want to live there. Terrible weather and no good beaches.

I disagree with you on that. I think Wellington urban beaches are actually better than Auckland, especially the South coast

Auckland has an urban beach for everyone. If you like a creative arrangement of privately operated and public parking lots, Takapuna is the place to go. If you are more fan of for awkwardly placed on-street parking, Mission Bay is unbeatable. If you want to feel like you’ve earned that parking spot after a long and exhausting drive, go to Long Bay.

Wellington used to be like Melbourne, but its living off a reputation.

I last lived there in 1999 and I am a fairly regular visitor. With a few exceptions (e.g. waterfront) its done little in the time since. Put kindly, its stood still, which in reality probably means it has gone backwards.

You can’t escape seeing the Auckland in Sydney and vice versa. Their George Street is like Auckland’s Queen Street, and the Viaduct Harbour feels like Sydney’s Darling Harbour. They also suffer the same problem that if you want to go from suburb A to B without involving the city it’s a tough job taking public transport.

George St: what Queen St should be, even if with just bus and cycle lanes and no LRT.

Its just mind-boggling the opportunity to transform it over Covid has been missed. Presumably those in power are just waiting for the days the cars come back to cruise through (but not stop), giving the illusion of it being optimal.

Some brilliant news with a HOP card vending machine!

https://at.govt.nz/bus-train-ferry/at-hop-card/where-to-buy-and-top-up/auckland-airport-hop-card-machine

Now just to install them all over Auckland!

Will be done by the time HOP is discontinued.

Interesting post and links thanks.