Like both housing and heritage advocates, Auckland Council is rushing to put out a response to the recently announced Medium Density Residential Standards (MDRS) which are currently going through select committee. Last week, they had their monthly public planning committee meeting, much of which revolved around their submission.

There seemed to be a broad consensus between both councillors and their officials that somehow the changes would both produce little-to-no additional development, and yet would be ruinous for the “special character” and urban design outcomes for the city. Planner-in-chief John Duguid proclaimed that allowing enabling more housing than the Unitary Plan would be like “a farmer placing additional fertiliser on crops when we’ve already fertilised the crops, and it’s getting to the point where we’re damaging the very thing we’re trying to grow and nurture”.

No evidence nor explanation was given to explain how enabling more housing during a crippling housing shortage could possibly harm the city. Instead, the changes were just dismissed it as ineffectual – the real issue is apparently (a lack of) infrastructure while the Unitary Plan has already enabled “enough” capacity.

The cost of provisioning infrastructure is a common refrain from those in and around local government – with the typical policy recommendation being that it should be stumped up for by central government. While there are some infrastructure funding and provision issues to be worked through, this is mainly driven by councillors who want to deliver goodies to their electorate without raising rates to pay for them. More importantly, it’s not “upzoning or infrastructure”, it’s “upzoning and infrastructure”. And this upgrade is way overdue. Our streetscapes and transport systems are causing ill health, injury and death. Council and AT need to roll out a safe cycling network, a new programme of street trees and better footpaths, and an efficient, prioritised bus network over the entire city. But this isn’t something that needs to happen just where new development is happening, or just because development is happening. These networks are required now, to transform the whole city.

Likewise, zoned capacity is a distraction. A city-wide number misses the context of each site – what is the demand to live there and what is the infrastructure capacity to enable people to do so? Just zoning capacity to “meet demand” means that sites with more permissive rules will be more valuable to developers, so will continue to carry a land value premium which will be passed on to first home buyers and renters. Enabling everywhere will eliminate that premium, and is the pathway to proper housing affordability and choice.

A council more serious about the converging climate, housing, and congestion crises would not be so dismissive, but would rather be attempting to mould the new rules to correct past mistakes and ensure quality on the pathway to housing abundance.

Past Mistakes

Council’s appeals to urban design ring hollow given that there’s little evidence that they’ve cared for design up until this point. Auckland’s relationship to suburban intensification, both recently and historically, has been primarily driven by two primary typologies: infill and the sausage flat.

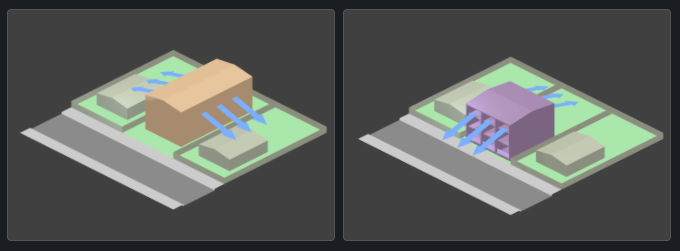

Developers trying to build multi-unit housing within typical suburban planning rules – which limit the ability to build to the property boundary at each edge to avoid imposing upon neighbours – has created housing oriented along the depth of New Zealand’s typically deep sites, with shared walls like width-wise cuts of a sausage.

With the walls parallel to the street front, this necessitates windows primarily overlooking neighbouring properties. In this way, planning rules which attempt to mitigate the issues with new developments, have the unintended consequence of actually exacerbating them.

The placement of the building within the site also serves its residents poorly: a sausage flat leaves thin strips of outdoor space adjacent to each boundary, too small to be useful for anything. If an entire neighbourhood were to be built out as this typology under the proposed MDRS rules, they’re likely to leave each other in semi-permanent shade.

‘Infill’ is a variant of the sausage flat, where you built several detached buildings within the same envelope. This can provide more outside space (although still compromised as a series of thin strips between buildings), but often with windows facing in all directions, exacerbating privacy issues.

These issues have led to a common notion in NZ that multi-family housing inherently has issues with privacy, lighting, and lack of space. This is completely unnecessary.

The planning envelope proposed by the government’s new MDRS rules weaken, but don’t eliminate, the planning rules which historically created these perverse urban design outcomes. This will ultimately reduce the amount of additional dwellings enabled by MDRS, as the risk of having your view and/or sun built-out makes medium density living less appealing, especially to families looking to put down long-term roots in a community.

What would an earnest attempt at shaping this mandate, and correcting these historic planning mistakes look like?

Future Opportunities

Enable Perimeter Block Housing

By bringing development right up to the front and side boundaries of the property, windows can become oriented towards the street and back, and all the open space gets unified as a single, large backyard.

This typology can be enabled simply by waiving all setback and recession plane requirements in the front 20 meters of the plot, and adding a shallow (for instance, 45 degrees above 3m) back recession plane, or deep back setback to disincentivise subdividing for rear infill.

This is common across Europe, and is sometimes called the “Traditional Eurobloc”. Named for when an entire block is built to this form, it creates a boundary of dwellings surrounding an internal greenspace or courtyard, which can either be a common space, or split into a number of private backyards.

With visibility towards the street and backyard, there’s no risk of peering into others’ living rooms. The outlook towards the street in fact brings a benefit: a phenomenon identified by Jane Jacobs as “eyes on the street”, which is thought to make neighbourhoods safer and build stronger community ties.

Unlike the sausage flat typology, the Perimeter Block Housing typology can readily be built side-by-side without imposing any issues upon each other. There is never any risk of being built-out as both outlooks (the street and backyard) are inherently protected. A direct neighbour building taller will have negibile effect on access to sunlight or views.

This means the typology can be incrementally built, creating a fine-grained streetscape, and can be responsive to demand: as an area becomes more desirable, stories can be added to existing buildings. You don’t have to destroy a building of one typology and build a denser typology in its place.

Corner Site Wildcards

Corners sites are generally the most preferable to redevelop, as they have the fewest neighbours to disturb. They’re also most accessible in the neighbourhood to other blocks, and can readily support multiple entrances. It would make sense to treat corner sites as a “wild card”, having no restrictions on the planning envelope (except the 3 story height limit) as well as allowing ground floor commercial (shops, cafes, retail, etc). The more permissive envelope would encourage those sites to be developed before others on the block, allowing shops to open and start providing amenity before future residents move in. This is particularly important as a significant proportion of New Zealand’s transport emissions come from short trips, which could easily be replaced by more local shops in walkable neighbourhoods.

New Zealand is also chronically lacking ‘third places’. Most people have two primary social environments – the first, home. The second, the workplace. Third places are “where you relax in public, where you encounter familiar faces and make new acquaintances”. These facilitate the spontaneous urban interactions that Jane Jacobs argued build the social capital which is a foundation for building communities.

Urban planning in New Zealand has been largely reduced to mitigating the negative effects of change, which planners have figured out is easiest when you just stop change in the first place. But true planning needs to look ahead, and see the needs that change will bring. Intensification can’t just be stacking people in houses, it has be building communities.

Increase dwelling threshold for consenting

One of the parts of the proposed legislation which made the most waves — allowing 3 homes by right in every major city — is also the least radical. Auckland’s Multi-Housing Suburban (MHS) Zone and above already allow 3 units per site as a permitted activity. This covers the vast majority of residential areas in Auckland. The primary change in the legislation is a more permissive envelope, allowing more floorspace per site. Allowing more floorspace per site without allowing more dwellings per site is likely just going to mean bigger (and consequently more expensive) homes.

As I’ve outlined previously, high quality townhouses can often be at a density of 5 or 6 per site. It’s not clear what value the dwelling limit provides, particularly if it’s limiting these. Raising or eliminating the dwelling threshold for resource consents would help create much more liveable housing.

We are likely to get greater urban design outcomes by putting our faith in architects rather than urban planners. But no matter who is in charge, any mass building program will be plagued by at least some decision makers with poor taste. Fortunately, there is no house ugly enough that they cannot just be hidden behind a couple of street trees.

Keep and expand these rules to rural areas

While the discourse has focussed primarily on intensification within urban centres, the proposal is not just “Auckland rules”. Eliminating minimum subdivisions sizes and weakening setbacks will enable a wide range of diverse “tiny house” typologies:

These typologies enable densities greater than the typical suburbia that characterises our small towns, without imposing large structures to those who are looking to escape a more urban form. Auckland Council have labelled small townships that fall within its border like Beachlands getting “Auckland rules” as a perverse outcome. They are mistaken. In fact, Parliament should consider extending these rules to Tier 2 cities – places like Queenstown, Dunedin, Nelson, and Napier/Hastings would all benefit from these rules.

Conclusion

If you – like me – are worried about parliamentarians only hearing bad-faith fear-mongering by those who just oppose, please submit before the 16th in favour of housing and suggest changes like these to improve urban design outcomes.

Council’s whinging response to the MDRS proves the government was right to do it. With the NPS-UD, Three Waters, & MDRS, the government’s appetite for taking power from local governments is only growing with time. Unless Council change tack, they will have progressively less and less power. After last week’s performances, Ministers could be seriously questioning whether to retain any local government control of zoning powers under the new RMA.

Processing...

Processing...

“the Unitary Plan had already enabled enough capacity”: maybe yes on the outskirts, but not in the central areas such as Mt Eden, Epsom, etc. Its probably more like a farmer using his best soil to grow corn and his worst to grow tomatoes.

Once you have Goff and councillors describing 3 level plans as ‘future slums or soviet style’ you know its no longer a balanced arguement and is just pure NIMBYism. Must be getting a lot of heat from rich owners of inner suburbs who probably haven’t clocked on that it will probably increase the value of their land.

I do like the idea of perimeter housing,but we will always come up against our old nemesis (the car),what do we do with it. Let’s face it ,almost every free standing house plan you see,allocates an extraordinary amount of the floor space to garaging,to the detriment of the overall design. Putting garages in bottom floors of multi storey is also downright ugly.

We do see some innovative solutions being offered,shared car,e bikes,etc,we need to unshackle these ideas,which are not new,the perimeter/terraced house has been around for hundreds of years.

Most perimeter housing in Europe sees the car parked at the back of the property, often at the expense of that green space envisioned in this pics.

That does happen. Also, the reverse happens, in which squares and courtyards covered in parked cars get a makeover, with the removal of the cars, and the planting of trees.

Changing regulations in order to create the city we want means we should think through what is needed to avoid the problems. Some rules about the maximum proportion of a site that can be paved, or used for car infrastructure seems reasonably straightforward for dealing with that one. Plus a requirement to reduce vehicle crossings. A targeted rate per m of vehicle crossing and another one per car space on the property would probably deal to it quickly.

It probably doesn’t help people get over old political biases when we use examples from the former Eastern Bloc.

Check out the Georgian & Regency mews and crescents in Brighton for an example of mass private housing projects with a certain conservative style. Regency Square, New Steine, Brunswick Town, Park Crescent.

For something a bit more organic, there’s the Laine and North Laine areas, also in Brighton. Mixed use, small form, live/work, partly pedsestrianized and no setbacks. Between Trafalgar Street and North Road.

Plenty of examples in Dunedin of terrace housing with no set back as well. Maybe sell perimeter housing as recreating those ‘heritage’ areas they so desperately want to freeze in time.

There are a few townhouse developments like that around central auckland, which have recreated multi-story “heritage villas” around the perimeter – Summerfield Villas in West Lynn, Domain Terraces in Newmarket. Big difference is that they were developed as a single large site.

Developing an entire block is high stakes. If you screw up you ruin the entire block. If many individuals develop independently it is much less likely that everyone screws up.

I endorse this comment as I currently live in Brighton (well… Hove, actually) and I used to live in one of those beautiful Victorian terrace in Kemp Street on the North Laine.

Outside the mass private housing projects (such as Brunswick Square and Sussex Square), the organic nature of the medium to high density development in Brighton and Hove leaves a more hodge podge aesthetic – which has its own charm and character.

I lived on Brunswick Road in Brighton (Hove, actually) and it was bloody brilliant. Super walkable and bikeable, real community feel, all those urbanist dreams come to life. Not perfect! But so different to NZ.

Moving back to Auckland was a big flip in perspective.

Thanks Scott. Great Post. The meeting was truly unbelievable. But when I expressed my depression about it, most people thought these were the last dying gasps of the adherents to the destructive zoning approach. Fingers crossed we’ll be over it all soon and can start to regenerate this city.

One councillor’s behaviour should have led to a resignation.

One officer’s presentation was appalling and steeped in misinformation.

Please submit. When the councillors are so poorly informed by their officials like this, it will take the public to put things right.

I can guarantee the councillors and staff will use the various exemptions (heritage etc) to the max to water down the density requirements in the ‘sensitive’ areas. Maybe a few more viewshafts.

We would never do perimeter housing blocks in Auckland. If someone did intensive housing around the edge then the second stage would be intensive housing in the middle to get the other half of the profit.

Perimeter housing was fine for Georgian gentlemen who could afford a share of a private park, but who would be the market here? If you could afford to rent or buy that then you could afford your own small private park. People who couldn’t afford it might prefer a small apartment built in the middle.

I think it would appeal to a lot of people who like the idea of looking out on a garden but either aren’t interested in gardening or would prioritise gardening below study/work/childcare commitments.

My central Auckland apartment block has a communal outdoor landscaped area that is in almost constant use for play by the various young families that live here. Much more social than if everyone lived in their own standalone house. A shame this sort of thing is illegal to build further out.

I have a lot of friends in Christchurch and Wellington who bought standalone houses not because they wanted a standalone house and a garden but because it was the only housing typology available. A shame they didn’t get a choice.

Yes I can see the internal area would make all the difference with kids. Mrs mfwic and I lived in Gilling Court in Belsize Park, London NW3 for 18 months. We only walked through the shared garden on the day we inspected the flat. Almost nobody used it except the few parents with preschoolers. But that was because the Heath was nearby and Regents Park a bike ride.

But the problem with perimeter blocks is that if land is worth building to that intensity on the street frontage then it is probably worth building on in the centre too, and most people wouldn’t have the money to afford to buy a share of land at that price to keep it empty.

Except you’re only allowed to build on 40% of the land anyway (for mixed suburban, at least). I’m not sure what the new regulations will allow, but there will still be max site coverages. If we’re going to require some of the land to not be built on, it would be better in one nice internal chunk that serves a purpose instead of some useless strips around the edges.

Then again, I’d be ok with them developing the inside as well, as long as they provide a decent streetscape between the buildings and make it public. Either way, it’s useful.

So, a sausage flat occupying 50% of the site is affordable, but a perimeter block occupying 50% of the site isn’t. Is this the lesson of the day on Miffy’s Mischievous Mathematics?

Where is the proof of your claim that a sausage flat on 50% of a site is affordable? More advocacy dressed up as evidence is it?

The perimeter housing obsession here is somewhat bizarre, and totally unrealistic.

It’s a lovely typology, though.

In the past, as I’ve blogged, these same Council officers have argued that some percentage of development needs to happen in greenfields locations because the feasible development within the city isn’t high enough.

The transport officials have then determined that sprawl roads and widened motorways are required to “support that growth”.

Now all of a sudden there’s “plenty of capacity” and no more is required.

Which is it, Council’s Planning Manager? It appears you’re wanting both:

Sprawl because there’s not enough capacity in the brownfields locations, and

No intensification because there’s enough capacity in the brownfields locations.

I call bullshit.

When do we stop wasting our money on sprawl roads and infrastructure entirely?

When do we get the upgrades to our city streets that we all need?

Heidi these are the same Council officers who have spent the last few years trying to ‘protect’ the city from its own Unitary Plan.

miffy, what gets me is this. The MDRS will shift the development capacity:

– away from the outskirts, where it imposes enormous transport and environmental impacts on the city

– inwards, to areas where people will benefit from the increase in amenities and services, bringing a better, more connected lifestyle to many people and vastly reducing the city’s emissions.

Some of the councillors already knew that planning officers were denying the emissions reductions potential of urban form; they knew what behind the scenes bullshit had been worked upon the ACP, and that there was actually a real gap in climate knowledge.

Why did they not push back on this disinformation at the workshops and prevent these officers from bringing it to the meeting?

Yes. I support the idea as it will give people more choice. Nobody has to intensify if they don’t want to. But it is promoted by people who don’t understand how a Council actually works. The simple fact the Government has put it forward has already changed the way Council planners are thinking. In their minds if someone will be allowed 3 houses on one site then they believe they should make sites three times larger. If their density rules are threatened then they will look for some other reason to limit intensity. Look out for new permeability rules, or retention rules or some other way of wasting space to defeat the Govts. intention.

Do you *really* think lots of small, ad hoc medium density developments scattered through wide swathes of suburbia is a good thing in terms of supporting PT and reducing car use????????????????

Because it’s not.

Based on what, Zen Man? Larger developments will also be good, including government built ones.

Building more homes is an excellent way to increase residential support for local businesses, services and public transport, to increase the rates base to fund local improvements and to enable people to live near their family and friends. In plenty of Auckland suburbs, shops are sitting empty; more residents will allow the empty shops to be filled with new businesses. More density in these places increases the number of activities that people can do locally.

This is why for some places, “infill” is considered the action with the biggest potential for reducing emissions, eg Sacramento:

https://coolclimate.berkeley.edu/ca-scenarios/index.html

Do they directly disagree with the PWC report?

The MDRS report directly states that this policy will enable more housing and prevent massive transfers of wealth. Do they not think so? Have they stated where they think that the report is wrong? Do they have a better solution that will achieve the same results? or is just privileged voices realizing their free ride is stopping.

I think its becoming more and more transparent what the issue is here. Council planning rules are being primarily used as a tool to create and entrench ‘lazy’ suburbs that do not pull their weight, and entrench wealth and transport inequality.

Transparently using government tools like this is absolutely not on.

My goodness I hope they open some of these meetings up to public speeches. I’ll be there, and they should be forewarned, I won my year 5 speech competition.

Also @admin one of the pictures is broken.

Thanks, fixed.

An informative article on the issue Scott. On the point of making submission to the Bill, what are the key things that we should highlight in a submission in order to specifically ensure these positive urban outcomes aren’t watered down by council voices? I want to make sure colleagues and similar-minded friends can submit and be heard, but I am unsure which elements of the bill to specifically address as well as recommendations to be made.

Multi-family housing has a risk which for me is even more averting: these blocks often need to be fixed and it takes years to do. For example the 20 Charlotte Street at Eden Terrace is about to undergo recladding which will take almost a year to finish and all residents should vacate the building for this period. This is really gross, that you have a risk to go out to the cold and to keep paying mortgage because some part of a building is not quite up to. Of course with current prices there’s simply no choice for first Auckland home buyers other than buying an apartment, so this doesn’t really worth a discussion.

People often have to move out of houses for renovation and recladding issues too.

This is not a valid argument.

With your own house you have a choice of just placing a bucket under the leak, or using Seoul-style fix with peace of plastic – nobody can kick you out. Also it usually takes a lot less time with a smaller dwelling and you can plan remediation dates. The bigger the building the less control over situation.

So you agree with Scott’s suggestion that each site should be developed individually instead of as part of a bigger development? Which requires being able to build to the side and front edges. This would limit the number of homes within each actual building.

Yes, Derek, absolutely.

What you are saying is only true of buildings subjected to body corporates, or held as unit titles. Owners of attached houses on freehold titles cannot be forced to repair unless the condition is actually unsafe, just like standalone houses on freehold titles.

There is also the problem of being financially tied together with other households. Maybe some of the occupants can’t afford a permanent fix right now.

Live in your own house while it’s being renovated or rot for eternity in hell – pretty much a coin toss really. I tried the former and next time will opt for the latter.

Personally I think this article offers a much more accurate perspective on the MDRS.

https://www.1of200.nz/articles/housing-at-any-cost

There is no shortage of land for housing in Auckland. There is a lot of landbanking, which gets scant attention.

As there is no shortage of land for development under existing rules, changing the rules will not deliver a great surge in housing.

But I do give full marks for the spin: “enable more housing”. What this actually means

* deregulate so that developers can be indifferent to the effects of anyone but themselves

* remove people’s democratic rights so that they have no say over decisions that affect them

A couple of weeks ago this blog ran a post supporting participatory processes. Here it is advocating the removal of democratic rights. This seems to me to be a major flaw with Greater Auckland’s advocacy position.

Landbanking is only a viable strategy when there’s a shortage of land with zoning that enables redevelopment. If there was no shortage then there would be no expectation of capital gains.

So is landbanking rife or is there a shortage of appropriately zoned land? You can’t have it both ways.

Ummm – no. Land – ie geographical area – is both an abstraction, and (cute concepts like reclamation aside) a fixed quantity In that sense, the supply of land is fixed.

What I refer to is that there is a large number of sites that are available to be developed for housing etc under present planning rules at present but are not being developed. The reasons for this “banked land” are at the moment unknown, but informal conversations with developers suggest it has very little to do with planning rules.

Landbanking as a concept refers to a strategy adopted by people who expect the value of land they own and development on it to be higher in the future than the present. This long predates planning as a concept.

“Informal conversations with developers” show that not only do the planning regulations make a whole lot of difference, but the Council planners skewed application of them make even more.

Fair enough – so you would be prepared to say that the large amount of land used for parking in the central area is that way largely because of planning regulations?

I’m under the impression that both this post and the post you linked are arguing that the current proposal is too blunt and that we should have a more form based code.

Also the last persons to comment on this should be architects. People universally loathe modern architecture. That is one of the main reasons why NIMBYism is going so strong.

Using the term NIMBY is just a way of othering people to avoid recognising them as people or listening to their views. It’s an (admittedly mild) form of hate speech.

Objectively speaking citizens have almost no input into decisions around development at present and the technocratic centralism of the current government is likely to remove even the possibility of input.

NIMBY is a term used to tell someone that you have listened to their views and realised that their views are hateful.

I believe you are making my point. NIMBY is now used to mean anyone who disagrees with the supply side lobby. If you genuinely believe empathy and compassion, and support for collaborative problem solving, can legitimately be considered hateful then I wish you most well.

“support for collaborative problem solving” is hateful when you think that changing neighbourhoods is a bigger problem than people living in cars.

What is hateful is cynically co-opting the sufferring of others to push a neoliberal agenda that will do nothing to help those in need The key to addressing homelessness is increased public investment not deregulation. Please read the Rebecca McFie article I posted further down.

And yes – I think that the current proposals are far too blunt and will cause immense harm that future generations will have to deal with. I would advocate for a focus on underutilised land coupled with participatory development of community level plans to accomodate increased housing in ways that build on the strengths of communities and enable them to welcome newcomers.

“People universally loathe modern architecture. That is one of the main reasons why NIMBYism is going so strong.” Absolute rubbish. All sorts of people like all sorts of architecture. Many people like bland pathetic architecture with no taste at all – take Tauranga as a prime example. But good architecture – aaah, there’s the thing. Everyone can recognise good architecture, whether modern or not. Quality lasts….

“Enabling councils to determine which areas were to be developed when, in line with infrastructure planning, would also enable more cohesive neighbourhoods of similar density to grow up, before the next area is tackled. Councils need to be able to identify key locations suitable for rapid intensification (for example Great North Road as it rises from New Lynn to Kelston, or the central area of Glen Eden around the library, playhouse, shopping area and train station) and masterplan these for location, orientation, and typology, to achieve the desired density while enhancing the urban form. This would enable a focus on infrastructure upgrades and construction suitable to the planned end result.”

How convenient, not in any wealthy peoples back yards.

Keeps land prices higher by giving people / developers no choice about where to build.

Consolidates building to maximally impact one community instead of having lazy suburbs not bearing their fair share the load.

Puts development further out of the city than it will otherwise be under the MDRS.

The classic anti developer sentiment is what gets us into this position all the time. “they wont build any car parks” so parking minimums are required with bumps up everyone’s house prices.

“they build in less desirable places way out of the city”, because its illegal to build closer.

“they build really small homes on small plots”, so local government makes it illegal to have a small home. What if I was a damn small home on a small plot.

All the anti developer sentiment achieves is putting up prices and taking away peoples choice.

Also:

In areas like Ponsonby and Grey Lynn, where the planning maps get finer grained

What in the world do they mean by finer grained in Ponsonby. They mean overwhelmingly a stifling, no build zone, open air museum, in the most convenient transport land in the city?

https://imgur.com/zUJyGGR

smh

Hmm – where do you think that sentiment comes from? Experience maybe 🙂

Hmmm where do you think the anti NIMBY sentiment comes from? experience maybe? 🙂

Have you thought about a participatory approach with developers, have they ever been asked how they could make other members of the community think someone’s new home looks nice?

Participatory approaches ought to involve everyone. That is fundamental. The group I see refusing to engage are the supply side advocates. In my experience to date, supply side advocates refuse to participate in panel discussions unless they can ensure only like-minded people are on the panel. In generals supply side advocates rely on abuse and dismissal rather than evidence. In general supply side advocates resort to false dichotomies to polarise people and win support for extreme views. So yes I agree there is problem with people being shouted down but probably not in the way you mean.

Property development is a business. Like all businesses some people are ethical and some are not. I am very keen to see creative discussions about how we deliver great housing and great liveability and the role of property developers in that conversation is critical.

But what I think underlies your statement is a belief developers own property and should have all the rights and any intrusion on their ability to make money to be by agreement.

At heart what I hear you saying is that private profit and unrestrained property rights are the highest good and will deliver the greatest benefit. To me that approach is what has brought us to the edge of climate catastrophe and created massive social inequality.

That approach is also what has created our housing crisis, not a relatively liberal planning regime that means people have to consider the impact of development on others to a limited extent. In crude terms, we have more houses per person in this country than ever before and yet we have massive homelessness and a major affordability crisis. We are building homes faster than we have in decades and yet most are being bought by investors.

To me these are not problems with the planning regime, Rather it is an easy scapegoat for people who want to take young professional’s attention away from the accumulation of property wealth in a small number of hands 🙂

If you are actually interested in how participatory processes can work, I’d love to have a proper conversation.

In crude terms, we have more houses per person in this country than ever before

Based on some numbers, dwellings vs population, I pulled from Stats NZ this is false. Don’t know where you’re getting this from in that case?

If you are actually interested in how participatory processes can work, I’d love to have a proper conversation.

I am genuinely interested in how you would plan on giving ‘imaginary people’ as a wellington councilor so lovingly recently put it, aka people who are not yet part of the community, people that would move in but are currently being excluded, children who would be born if there was more housing in the area etc etc, a fair say in these things.

I think giving existing community members, people that are privileged enough to already be included, any advantage over current outsiders in the outcomes is clearly bad and is what leads to bad outcomes.

According to Stats NZ – dwellings per person rounded to 2 decimal places.

1986 0.30

2013 0.35

2021(estimate) 0.37

This aligns with work cited by Rebecca McFie in the article cited elsewhere.

I’d be the first to argue there are a huge number of factors are in play, and analysis needs to be granular. But people love talking about supply of houses in aggregate so I thought its useful to look at the data in aggregate. If you read the Rebecca McFie piece you’ll see there is no homelessness in the early 1980s. Just sayin’…

One of the great tricks used by neoliberals and right-wing tyrants alike is to claim they are acting on the interests of a voiceless group as a reason to take away democratic rights.

The implicit assumption you are making is that democratic processes are captured by people who are purely selfish and that technocrats and markets will do a much better job of looking after the interests of the voiceless.

I find it fascinating you think

(ii) a group of people can’t recognise that there are interests not represented, that no-one can advocate for those interests, and that

(ii) a bunch of technocrats and property developers will do a much better job of looking after those interests.

That has worked really well with biodiversity, climate change and most other ecological crises right? Grass roots indigenous solutions to ecological crises just get captured by NIMBYs all the time 🙂

The arguments you are making are directly borrowed from the neoliberal argument against employment laws and unions. They say that these create privileged insiders and leave an unrepresented group of poor people who can’t compete for jobs. If we took away these privileges (union rights) then the system will be much fairer. Nothing new under the sun when it comes to neoliberal arguments 🙂

Deflect, dodge, deny these problems exist. You’d make a good politician hey?

you think a group of people can’t recognise that there are interests not represented, that no-one can advocate for those interests

This is a really silly argument. could be summed up to be: “trust us to represent interests of voices that aren’t here mate”. I never said that people don’t try to do that, but its like holding back the tide with your hands. The outcomes will always be skewed to primarily represent the voices and ideas of the people that are part of the group represented.

So yes I think trusting the technocrats of the much more representative, very stable, governmental level that is designed to take into account the voices of a much wider area / larger group, that includes me, is a better idea than trusting a much smaller group that doesn’t include me.

You also seem to really love trying to collect ideas into groups. “The arguments you are making are directly borrowed from the neoliberal argument against….”

So what? Who cares what you think these arguments look like in different arbitrary contexts?

Our poor urban form and transport system have been created by an unhealthy democracy; one in which landlords get extra votes, youth are excluded, CEO and Board appointments are made using skewed and undemocratic values, (as a result) commitments agreed to by councillors are ignored by the CEO, the expected quality of technical information from transport and land use planners is missing so councillors vote in a misinformed way, councillors therefore don’t even realise they need to follow up with the CEO when commitments are ignored, people who want to live in an area don’t get to vote for a councillor who would enable that, public sentiment is gauged using reckons, the inequity created by the political economy of car dependence leads to a loss of democracy, and so on. And on. And on.

Scott is not advocating for the removal of democratic rights. Your idea of democracy is overly simplistic.

Heidi – I agree there are problems with the current system, but I beg to differ that taking away people’s right to have a say in how development affects them is an improvement. Would you apply that generally – eg lets abolish local government because turnout is low and instead have experts appointed by central government making decisions? What happens when voter turnout drops at general elections?

Scott is advocating for a deregulated system where technocrats set rules and local people have no say in the consequences. As I have said many times, and this blog has advocated for in other situations, a broad participatory process is important.

My observation is that in general pursuing deregulation implicitly assume they will be the winners in a technocratic system and really haven’t considered what it is like to have no say to what is done to a place where you feel a sense of belonging.

Loss of agency is one the major causes of community trauma and is a major issue for lower-income communities generally, Seeing loss of agency as a victory seems to be going precisely in the wrong direction. But y’know good luck 🙂

The problem is that if everyone has absolute agency in their local area, they still get to externalize costs onto other areas. A race to the bottom, unless a larger agency comes in stops is.

Ponsonby saying “no development” isn’t some win for local democracy, it just means that some other area bears more of the load. They should be compelled in some way to not make others lives worse through their actions.

really haven’t considered what it is like to have no say to what is done to a place where you feel a sense of belonging

There is also level of privilege here, that assumes that all that many people have a sense of belonging in their communities at all, especially young people. They are very unlikely to be able to own a home and put down roots. Perpetually shuffling around between neighborhoods.

Why should they care about community agency, when the first past the post, unrepresentative local government, consistently tries to create systems that contribute to them not being able to be a part of the community?

If group x is actively making rules that make group y’s lives worse, then why should group y be expected to support group x keeping its exclusionary, externalizing tools?

It’s 3 level housing, are people forgetting this. Hardly a housing revolution for a City of over 1.6 million people. If you live in a central suburb in a global City and the biggest City and economic powerhouse of your country and are worried about the changing on your streescape a little or some shading maybe it time you know, didn’t live in a City. There is your democracy, you can vote with your feet and take your massive capital gains you’ve locked in for so long.

People saying they are worried about future generations when future generations are on track to never afford a house is a bit rich.

One way to do this democratically would be to greatly increase localism. Those owning a section would be able to develop it more intensely providing those who agreed to buy or rent houses on the property voted in favour of the development. In addition, those working or studying in an area should have a say over zoning laws, especially if they would like to live closer to work or a tertiary institution.

Allowing higher density housing also democratises consumption. In addition, governments have promised to make housing more affordable and to protect the environment, and this involves more inner city housing.

You seem to assume that I think participatory decision-making ONLY applies to Ponsonby. I am suggesting that it can be used everywhere. You are the one who rejects out of hand the idea that we can ask communities “how can you welcome more people” and get a sensible answer. Ponsonby has never been asked this question and nor has anyone else. Nor has the state done anything to create affordable housing in those areas.

Build-to-rent can fit in to dealing with single building management. Of course, some realistic quality control and management can help, recognising the materials and labour pressure that threatens quality.

Two thoughts:

1) vehicle access and storage: what makes sausages so horrible is the space taken up by shared driveway and garage/carport/hardstand (i.e. every sq. m not dwelling). A similar threat to good perimeter build is every “living room” being a garage instead. Some kerbside parking and access to whatever parking is necessary at the centre or end of the block is better, with one or two vehicle accesses per street block. How to achieve that becomes the issue to solve.

2) Incremental development: to avoid sausages or vehicle crossings dominating narrow dwelling frontages, the steps toward desirable perimeter blocks needs to be worked out. Local Framework Plans may be necessary, to co-ordinate development over time and perhaps to share equitably cost and value. It’s not just overshadowing, it is about how to move from one type of housing to another step by step, including the issues of land value.

I think unless you can get away with providing less than 2 car parks per house you are SOL. Either you have the parking on ground floors, or it fills up the entire courtyard. Or maybe have a row of diagonal on-street parking and no driveways.

The other possibility is private parking garages, which is how we do it in the city centre.

As far as I can tell, there is no way of doing higher density that is both nice and has 1.5 to 2 car parks per house. The only way out is building in places where it makes sense to not have that many cars. Which are mostly the places currently covered in heritage overlays.

“As far as I can tell, there is no way of doing higher density that is both nice and has 1.5 to 2 car parks per house. The only way out is building in places where it makes sense to not have that many cars. Which are mostly the places currently covered in heritage overlays.”

Another perspective is that anywhere which has good local services easily accessible by walking and cycling and great public transport is a location where one can build without parking. The key to rapid emissions reductions is in fact focussing on creating focussed increases in density, amenity and transport choices in low density areas. This relocalisation or retrofitting of surburbia is the key way by which intensification can reduce emissions. Building more housing in areas that are already relatively dense and have low emissions does nothing to reduce existing emissions.

Given scarce resources and a social choice between the two, the urgency of the climate crisis suggests that we ought to be focussed on relocalisation.

“The key to rapid emissions reductions is in fact focussing on creating focussed increases in density, amenity and transport choices in low density areas.”

Yes, in fact this is true in any area with density lower than what its natural density would be, given its location.

On relocalisation, is that something you have experience of? My experience of community attempts at relocalisation has shown me that it requires the same things that will enable densification: a focus on liveability and green infrastructure, streetscape and traffic circulation changes, urban form that mixes amenities with residences, an increase in the ratio of people to cars. This is true in the inner areas of Auckland’s isthmus as well as in the outer lower density areas of Auckland.

Yeah it makes sense around all those smaller centres too. But these areas are already less heavily restricted than those central suburbs.

I am not sure I buy into the idea of “natural density” anymore than I do the “natural rate of unemployment”. Settlements are human constructs and so are the decision-making processes which shape them. The conceit that democracy impairs some “natural” market outcomes is rabbit hole which, I offer, leads to very dark places 🙂 My preference is to address issues through participatory democracy rather than abolish democracy.

Leaving that aside though, New Zealand hasn’t really attempted relocalisation but I am familiar with experience in North America and some other jurisdictions. I am absolutely agree the factors you mention are critical. If we add in a climate lens though then its clear that creating a network of urban villages / 15 minute communities ought to be the priority.

Participatory democracy is useless if people who stand to benefit can’t participate. Deliberative democracy in which youth and would-be residents get to make the decisions about areas and environments where they will be living in future – hopefully – would be far more useful than giving the decisions to those who have benefited sufficiently in the current systems to already be living somewhere.

Heidi – so to be clear, if one of these young people buys a house they then cease to have any right to a voice? Because your version seems all about conflict and a static us and them, and “win-win” solutions can’t get a look in?

I remain curious why you see people who own vast amounts of property and sit on their hands as find and dandy and instead focus your opprobrium on older people who may own a single house. They were young people without a home too at some point. They are future you. Housing looked just as unaffordable at age 25 in the mid-80s or the early 2000s.

At some point in the future, and even now, you may feel a sense of connection a place. I just wonder whether your future self will thank you for making sure you have little or no say in how it evolves. You yourself have advocated for participatory solutions to other issues so I am curious why you think it can’t work here.

There are constructive solutions to provide homes, protect quality, and ensure all people have agency. This blog and other supply siders seem to prefer polarisation and conflict around an ideology that is impervious to evidence. I will continue to advocate for empathy and compassion informed by good evidence.

“Housing looked just as unaffordable at age 25 in the mid-80s or the early 2000s.”

Please try to keep up.

Feel free to check the RBNZ statistics, Core Logic or any other reputable data source if you disagree. Biting my tongue otherwise.

Mid year 2001, Auckland median house price was 4.2 times the Auckland median household income.

Mid year 2021, Auckland median house price was 11.2 times the Auckland median household income.

A fairly basic index yes, but it does show the simple fact that the on average houses are three times more unaffordable than they were twenty years ago.

https://www.interest.co.nz/property/house-price-income-multiples

The Median Multiple seems to be widely used as measure of affordability even though it is seriously deficient and has long been critiqued on that basis.

The largest and most obvious flaw for present purposes is that it takes no account of financing costs. This implies that house prices have no relationship to interest rates and so reinforces an extreme supply side view. That is unsurprising given its origins as a measure designed to undermine arguments in favour of denser urban areas 🙂

In a world where there is some convergence in interest rates across nations at any point in time, one might argue the median multiple has some value as an indicator in cross-sectional terms. As a time series measure it is worse than useless, and provides a wildly inaccurate indicator of affordability of house purchase in relation to income.

Core Logic uses the cost of financing and a separate measure looking at deposits. These give a more accurate picture compared with the median multiple figures. The gold standard is a composite indicator measuring cost of finance and deposit in relation to median income.

Looking beyond simply the cost of purchase, household domestic energy and transport costs are also important. Median multiple, and the Demographia survey, are highly poilitical exercises. They were originally developed to support an argument that sprawl led to cheaper housing, and critiques focussed on the neglect of transport costs. More recently it has been used in some countries to argue the extreme supply sider position and has been criticised for neglect of finance costs.

If you want to say there is significant risk associated with borrowing long term at lower than historical average interest rates then I would agree. But the statement that housing has become less affordable over time solely on the basis of the ratio of purchase price to income is a deeply flawed claim.

It does however help feed the climate of fear and anxiety which reduces critical thinking and means people are more susceptible to, and less likely to scrutinize, radical neoliberal ideas 🙂 The unpleasant maxim that if you want to tell a lie, tell a big one and repeat it often applies here. This tactic worked in New Zealand in the 80s and 90s and appears 1- 2 generations later to be working again.

What a disgracefully disingenuous post from you Roland. The multiples show how high the barriers to entry in the housing markets are. You need to borrow triple as much money as you would have 20/30 years earlier, that’s before taking into account stricter lending standards. No 100% mortgages, no 10% deposits. People are having to save for a decade before being able to buy, as the massive decline in the under-40s home ownerships rate makes abundantly clear. But god forbid someone tries to build anything other than a 4 bedroom villa on your street eh

Mōrena Kurt

The key is not the amount borrowed but the cost of that borrowing. That has always been the case. That is how banks stress test borrowers. As I say I agree there is a lot of risk in borrowing large at low interest rates and I am keen to see a lot more affordable housing. What I am challenging is an indicator of affordability and the winner-takes all deregulatory approach which to me is a house of cards.

I agree deposits are onerous but I haven’t heard anyone here asking that they be lower for first home buyers. Nor have I seen anyone address the issue of the collapse in public housing, investment, the reasons for large areas of under-utilised land, the fact that the rise in house prices has largely been driven by investor demand, or the fact that the building industry is running white hot, and rents are actually falling in many parts of Auckland at the moment.

Implicit in your comment is the view that anyone who disagrees with the supply sider / deregulation model is against providing housing. The claim that anyone who disagrees with a particular solution doesn’t care about the problem is at best a cute rhetorical device. Put another way, I do not believe that I am the one being disingenuous 🙂

Also, I was around when Demographia was started and I know very well the reasons and motivations because people like Owen McShane were very clear about them. I am reporting first hand conversations in my earlier comment.

Go most well.

Mōrena Kraut

The key is not the amount borrowed but the cost of that borrowing. That has always been the case. That is how banks stress test borrowers. As I say I agree there is a lot of risk in borrowing large at low interest rates and I am keen to see a lot more affordable housing. What I am challenging is the value of median multiple as an indicator of affordability and the winner-takes all deregulatory approach which to me is a house of cards.

I agree deposits are onerous but I haven’t heard anyone here asking that they be lower for first home buyers via regulation. Nor have I seen anyone address the issue of the collapse in public housing, investment, the reasons for large areas of under-utilised land, the fact that the rise in house prices has largely been driven by investor demand, or the fact that the building industry is running white hot, and rents are actually falling in many parts of Auckland at the moment.

Implicit in your comment is the view that anyone who disagrees with the supply sider / deregulation model is against providing housing. The claim that anyone who disagrees with a particular solution doesn’t care about the problem is at best a cute rhetorical device. Put another way, I do not believe that I am the one being disingenuous 🙂

Also, I was around when Demographia was started and I know very well the reasons and motivations because people like Owen McShane were very clear about them. I am reporting first hand conversations in my earlier comment.

Go most well.

You can keep writing ‘Go most well’ as much as you like Rolan but the relaity is, you clearly have absolutely no idea what it is like to be a 25 year old trying to buy a house. Absolutely zero! You can read artciles and be as academical as you like but literally go speak to anyone trying to get together a deposit through their own saving followed by a large enough mortgage to even fund a house at an ‘affordable’ level. Impossible and if it wasn’t we wouldn’t have literally millions of people between 20-40 saying so.

So write all you like, but you have zero clue. I’m can only asusme you spend all day on the internet and haven’t had a proper converstion with your ‘average Joe’ trying to buy a house.

Go most well.

Yeah, I have zero clue, I’ve never rented, been on the DPB, been turned down for a mortgage, wondered how I would every pay the power bill, been evicted by capricious landlords or anything else 🙂

The system we have now is rubbish. The reforms supported by this blog will be worse – for young people, old people and everyone else. That’s my core point. There are better solutions and they are being ignored.

“The largest and most obvious flaw for present purposes is that it takes no account of financing costs”

So…what are the financing costs for, say, a $500k 25 year mortgage, Roland? To keep it simple just use a mean figure for each of the next 25 years.

Cheers.

MFD – for some reason the reply I posted to you appeared at the bottom of the blog. My apologies – I am not sure why that happenned… all I did was hit reply and post. Please see below re affordability and finance costs.

The biggest factor in the cost of borrowing is the cost of the bloody house!

My first little studio I bought in the early 00s cost $125k: $25k deposit and a hundred grand mortgage at 6%. Affordable, ish, for a single guy fresh out of uni with a couple years savings.

The same place recently sold for $550k. That’s a $110k deposit and a $440,000 mortgage. Sure the mortgage rate is only 3.5% but the deposit is still four times the size and the repayments triple.

Yes, private parking garages make a lot of sense for a number of reasons: the costs get properly contained and assigned, the vehicle crossings are properly consolidated, etc.

And building “in places where it makes sense to not have that many cars” would be extended to almost everywhere with proper Council direction of AT’s programme of work. Our deficient transport system is only there because of resistance to change. We could overhaul it quickly if we had a leader.

To be honest this article is arguing for exactly the same thing as many submitting on the plan including many – albeit not all – in council. Yes, we need more density. Please can we do it well because those with few options will have to take what they can get. It would be nice if housing for those less well-off is thoughtful, with light, and safe access for kids and seniors to get to the pavement and some green space rather than designed simply to ensure a good yield. Perimeter blocks and form based codes would be brilliant. They are not in the proposal at the moment. Please push for them. The proposal doesn’t promise cheaper houses prices just slower house rises. Is this good enough? If not, submit on that. Why shouldn’t we push for lowering the price of houses across the board? This feels analagous to making a chocolate bar cheaper by reducing the size of the chocolate bar. Houses are far more expensive than they should be – just compare them to those in London or Tokyo. Ponsonby and Grey Lynn are often raised as areas of high protection and there are protected bits but there is also lots of intensification happening right now on the West Side, down Jervois Road, Great North Road, Ponsonby Road, Richmond Road, around Karangahape Road and in the City Centre and Parnell and Newmarket. A lot of it is 6-8 storeys. Some of the “luxury” flats don’t have bedrooms in the windows. So, what does that mean for the affordable stuff? there is a huge amount of contempt of council as a monolothic beast that is always anti everything but look at Wynyard? It’s great. Can’t we have more of that sort of thing rather than more low density sprawl which is what is currently being proposed?

“This feels analagous to making a chocolate bar cheaper by reducing the size of the chocolate bar”

Which is perfectly acceptable, I don’t want the old legal minimum, king sized mega chocolate bar. I want a secure warm dry little chocolate bar that me and my girlfriend live together with no flatmates, so we can focus on other things.

Smaller chocolate bars maybe a good idea, but you expect them to cost less. new apartments, unless studios, or old ones in the central city, are almost as expensive as the villas they replace but there is no room for flat mates.

Yes but is that due to real underlying cost issues or simply a reflection of the crazy property market where even the meanest shack is supposedly worth $1 million +.

Actually Alex, I have an elderly family member (you may have met?) who thought she couldn’t afford to move back to Auckland after 30 years away. But she has done so this year, because she found a truly affordable apartment. Leasehold, yes, but because it’s small, the bodycorp, ground rent, and rates combined are really low.

Compared to the rates for a house on a full section and the maintenance on a whole house, it’s like black and white.

+1, such an odd comparison when most people buy a snack size chocolate bar, not a king size family block….

It’s actually quite surprising that council is fighting this…. You’d think that they could get the benefits of it while blaming the (few) downsides on government so as to not lose votes in local elections.

And yet – despite the lack of restrictions – it’s not happenning. Perhaps that is because the planning system isn’t the key issue?

Of course it’s not the key issue. This is another case of de-regulating in the name of ‘doing something’. Whether it’s a so-called centre-left party (actually centre / slightly right of centre in reality) or not, they all believe in the same neo-liberal nonsense.

Rather than the government actually taking some responsibility and doing the only meaningful thing that can be done – building much more social and affordable housing. Which BTW doesn’t need any of this nonsense, the government owns huge tracts of land, plus has the Urban Development Act if it wants to rezone.

This is a blatantly disingenuous government. Heck, look at their propaganda (images) around what could be enabled under the Housing Supply Bill – they just happen to show three storey development with a site coverage of circa 25% (rather than 50%).

Absolutely unbelievable.

Yes – I agree with your comments about neo-liberalism, and about public housing. I’ve posted below a couple of articles on this general topic.

Max Harris has an excellent evidence base around the fact that it is a lack of public investment and growing inequality rather than planning that explains our present housing. He bravely continues to make this point on Twitter in the face of the usual rhetoric 🙂

In japan, most residential area allow first floor to be used as light business activity without consent.

For example you will see home business sell noodles on the first floor and lives upstairs.

The light business includes small retail (convivence store, hair salon, butcher, fish shop, childcare, little co-op stores, artist workshop), and light food (breakfast, bakery, takeaways)

This makes the area more walkable and convenience without needing to drive to a town center.

“Futile Councillors Fight An Affordable Future”

Top marks for alliteration!

Politicians pining for property precincts of the past.

The Council is right. Zoning for density everywhere is ridiculous, ineffectual, counter productive and full of unintended consequence.

Some of the naivety on display on this website is quite staggering.

Do people not think that the desirable outcome of much more dense mixed use development in and near centres and train stations will not be eroded by this nonsense?

Because it will.

Why bother with costly and risky apartment development near train stations and centres when you can do dense terrace housing in the middle of wide swathes of suburbia instead?

And btw, this Housing Supply Bill will do jack-all in terms of housing affordability.

That’s not to say the Unitary Plan couldn’t be better. But the NPS-UD was going to do enough anyway, in terms of zoning for MUCH MORE more density near centres and train stations.

Sigh….

Land owners and developers will be laughing all the way to the bank however….

Economic transfers arising from the policy are driven by the slowing down of housing price increases over time. When the price of housing in a city rises faster than real wages in that city, the housing market slowly transfers wealth from non-homeowners to the owners of real estate over time. For most non-homeowning households, this means reducing disposable income over time, leading to greater inequality of income and of quality of life in urban society. This has been the case in Tier1 urban areas on average for the last 20 years.

The housing supply increase enabled by the MDRS [alone] reduces this transfer of wealth over time by narrowing the gap between the rate of real wage growth and the rate of housing price growth. We refer to this policy effect as a ‘transfer’ or ‘distributional impact’, though it is more accurately described as a reduction in the ongoing transfer of wealth from non-owners to owners described

above. The total cumulative value of this transfer, estimated as of 2043, is about $198 billion, or about $161,000 per household present in the five cities at the time of policy enactment in 2022—enough

for a deposit on a home. This $198 billion is the value of the forecast price impact multiplied by the total expected households in the without-policy case, in each urban area. This corresponds to the peach-shaded area

A reduction in wealth transfer, is a really funny way of putting laughing all the way to the bank.

https://www.hud.govt.nz/assets/News-and-Resources/Proactive-Releases/Cost-benefit-analysis_proposed-MDRS.pdf

I started work at the Ministry for the Environment the day after National was elected in 1990. I saw the birth of the RMA first hand, and also spent years working as an environmental economist dealing with the standard neoliberal rhetoric. I am very familiar with this type of cost-benefit analysis which is straight out of the 80s/90s playbook.

Essentially the conclusion is embedded in the design of the analysis. In fact, the proposed deregulation and externalisation of costs onto communities in the RM Bill will lead to an increase in the value of land – this will benefit existing land owners and increase rather than reduce inequality. It may also likely to lead to an increased rate of demolitions and vacant sites.

The problem with the CBA you cite is that it embeds the idea that the planning system is a significant constraint on housing whereas it is at worst a minor issue. At the same time, it ignores the issue of vacant and under-developed land.

Land – as in hectares – is in fixed supply and the relationship between planning and expected future value is very complex. The current acceleration in house prices is largely driven by wealthy investors whose purchases are enabled by banks who see these borrowers as a safe bet.

If you are genuinely interested in the causes and solutions to our housing crisis I have posted some articles lower in the comment section.

You say land is in fixed supply, now sure.

But actually that’s not what we need to build housing. We need opportunities to build housing, which are extremely expensive at the moment, and can easily be manufactured by regulatory change. You can claim its an inelastic market till you’re blue in the face but that isn’t the case as proven by the AUP. And we can see the direct comparison to Wellington which is the even more extreme “no build area”, with rents blasting past Auckland.

Now no one is claiming this is the silver bullet. Of course more social housing, tax changes etc.

The primary effect of the MDRS is expanding the up zoned areas to include NIMBY neighborhoods near city cores, forming a more equitable set of zoning laws. Your defense of the current laws or further restrictions to minimize impacts to the wealthy areas of the city is pretty much the definition of champagne socialism, I guess the natural career conclusion for green party members.

If you’re genuinely care a drop about sustainable transport and housing, you need to accept that Te Aro, Ponsonby etc, need to open up to development and have some places that serve only to make housing and transport worse, be shown the wrecking ball.

Opportunities for housing are not in short supply. What is in short supply is investment in the opportunities that exist.

You need to explain the vast areas of vacant and under developed land in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch before your argument has any teeth. In Wellington, Te Aro is already upzoned to 7-9 stories and has been for close on 20 years. The same holds for Adelaide Rd, Johnsoville Mall etc etc. You need to explain the lack of housing construction in that situation. How does the planning system cause this?

Also, factually, Wellington’s planning rules are less restrictive than Auckland’s. A smaller proportion of land is covered by demolition controls, and multi-unit development is more straightforward. This is a factual conversation so please if you want to debate this point, I’d be happy to compare documents.

Housing construction is rising under the AUP because prices have been consistently high and developers spot an opportunity. Wellington by contrast had a house price fall in nominal terms of around 15% between 2008 and 2009, and in the mid 2010s apartments were selling below cost. House prices four years ago were static in Wellington and only took off when investors began looking outside of Auckland. It has taken a long while for developers to have confidence in a solid return on investment again.

Data can be so inconvenient sometimes 🙂

And seeing you suggested what I might care about, let me respond. If you really cared about sustainable transport, the climate and equity you would recognise that intensification needs to focus on creating urban villages rather than reinforcing the wealth of those who own central city property.

We will get more housing faster if we focus on

* development incentives and public investment on land that is vacant or underutilised

* participatory planning processes to free-up capacity over the medium term

That is how most of the European cities we love to admire create housing.

By the way – my observation is also that supply side advocates prefer blog posts quoting other blogs and shy away from fora where real time debate can occur. I’d love to see some of the arguments that are run on this blog actually debated in a civil forum.

Talking about European cities, usually a few km from the city centre they look a lot like that image from Prague.

In comparison Grey Lynn looks quite “underutilised”.

Feel free to overlap a map of Copenhagen, Prague, Amsterdam or Brussels (to pick a few) on Auckland and come back to me if you still feel confident about that statement 🙂 Barcelona might fit your bill though.

Again, I ask though, why focus on demolishing buildings when there is plenty of available land, and you don’t make four people homeless to create space for eight!

OK, map reading time. This is Auckland, 2.5km from the town hall.

https://www.google.com/maps/@-36.8665594,174.7459234,368a,35y,345.84h,47.48t/data=!3m1!1e3

This is Brussels, 2.5km from the town hall.

https://www.google.com/maps/@50.8569415,4.3721554,285a,35y,330.96h,50.38t/data=!3m1!1e3

You can look up a few other cities if you want. It will all be the same. Maybe one more, what about Amsterdam:

https://www.google.com/maps/@52.3639192,4.8586335,156a,35y,327.29h,65.6t/data=!3m1!1e3

And of course you can check the image of Prague in the original post.

The general layout in Grey Lynn is already quite similar to that in the examples from Europe, the difference is that you still have 1 to 2 storeys instead of 3 to 6.

As for demolishing houses, that is up to the owners of those houses. Do you expect mass demolitions all of a sudden if the council lifts the height limit? I would expect many people will still keep living in their current house, and it will take a few decades for it to built out at the higher density.

We don’t even need to go for cities that big. These cities aren’t radically different sizes to Auckland (and some are smaller. Auckland (and New Zealand in general is developed far more sparsely than European cities because we have made a political choice to regulate higher density out of existence.

Le Havre https://goo.gl/maps/VWrjvWnydy9ymWCb7

Nantes https://goo.gl/maps/PxykteGzuMFeXmb19

Bilbao https://goo.gl/maps/PxykteGzuMFeXmb19

Turin https://goo.gl/maps/Cvd3gwhiLZ2axY9K7

Geneva https://goo.gl/maps/A2x6vTVCon9e5wSe6

Cologne https://goo.gl/maps/GMHzFppqS3ftgEKQ7

Stockholm https://goo.gl/maps/qminuzEPFnCrJ7tQ6

Roeland – thanks for sharing those links – I really appreciate you going to the trouble of doing so. I’ll have a nosy around and get back to you. But thank you.

“I’d love to see some of the arguments that are run on this blog actually debated in a civil forum”

1) This disadvantages peoples voices who have things to do with their days or nights. Or who’s lives are less predictable, flexible, or stable.

2) https://youtu.be/WdlXTJIL7Oc?t=78

This kind of forum disproportionately gives voices to loud members of society and actively tries to exclude less confident people.

Completely undesirable and unequal.

What on earth is your view of debate on a marae?

I have no idea what you’re talking about, nor see the relevance.

I don’t think saying forums enabling jeering at a group that is VERY clearly underrepresented in this meeting, is undesirable, is remotely controversial.

Interestingly, in my experience, the ones doing the jeering and abuse are the supply-side advocates. Twitter in particular is toxic in that area. The one session in Wellington which involved a live panel with different views was far more respectful and open.

If you have had different experiences then I am very sorry to hear that – civil discussions are possible, and I have helped create them many times on many different topics.

Solid rant zen man.

I agree actually.

Also, I’ve never been a fan of the RUB but, because I live outside it, I think it needs to be reinforced. Cause I don’t want this shit encroaching on me.

You’ve bought the Bullshit ‘hook, line and sinker’.

Zen Man (25+ years experience in urban planning and development)

(But I won’t waste any more time here with people who think they ‘know it all’, you can believe what you want :))

25+ years? Judging by your constant miserbale rants on this blog usually without evidence, maybe its time to retire and get some sunshine in your life?

Perimeter block housing is a great, and proven, urban typology. However, I don’t think it’s possible to get perimeter block housing by increments in the existing suburbs, it has to be master planned on a city block level. If a brownfield (or greenfield) site was developed with zero side setback rules, minimum front setback and generous back setbacks, and each block had to negotiate a party wall with its neighbour, then it could be really successful. The same with terraced housing. Not sure how much you have to worry about this in Auckland, but in Wellington we have to consider lateral movement in an earthquake, and you’re not supposed to shake over your side boundary. Some apartment buildings could potentially deflect by a metre or more, so the side setbacks will always be required if buildings are developed on a plot by plot basis.

I have returned to NZ after some time working in London, and there are a lot of rules governing access to sunlight and daylight, privacy and amenity. 18-20 metres is required between the back windows of facing apartments (12m for apartments facing each other across a street). A lot of councils also have rules against single aspect north facing (south facing if in NZ) apartments, or against single aspect apartments all together. All new housing has to meet minimum area requirements, which are far more generous than many NZ apartments I’ve seen advertised. There are also minimum shared outdoor amenity and play space requirements. And absolutely no internal bedrooms! I want to see NZ build at higher densities and for our cities to transform, but it’s so critical that good standards underpin this development.

Some further points – the proposed rules will also enable people to build giant houses or extensions that could negatively affect neighbours – the setback and height rules should only apply if you are creating multiple dwellings. Subdivision consents will still be required, so a lot of the new dwellings will target the rental market rather than would-be home owners. Hopefully existing rental stock will then be opened up for sale, particularly coupled with the rental income tax changes. I also think the three dwellings max is rather arbitrary. If site coverage allows, then the number of dwellings should be able to be increased.

Form based codes could be a good way to safeguard urban form outcomes while speeding up the consenting process. I don’t think getting rid of resource consents is the right way to go, but there does need to be a way of assessing development suitability and quality in timely and predicable way. I fully support increasing density across our cities, but I want to see good urban form with defined streetscapes, rather than sausage flats everywhere.

Overall, I think it will be difficult to successfully intensify existing suburbs in the ad-hoc way this legislation would enable, and I would rather see targeted development of brownfield sites to really unlock the best design and urban outcomes.

Rose, perimeter block housing developed in other cities without having to be master planned. Indeed it may be better if it is not. Roeland has linked this article before, which is worth reading: http://urbankchoze.blogspot.com/2015/05/traditional-euro-bloc-what-it-is-how-it.html