The Auckland city centre street network is, at last, about to undergo some proper change. As with any change it will face resistance. A fair bit of that resistance will come from people who are simply used to how it is now.

So I think it could be a useful exercise to examine how it got to be like it is.

And interestingly, unlike the fairly varied and layered nature of the city’s architectural condition, the design of our city streets is not the result of some natural accretion of styles. But rather it is the outcome of sustained and coordinated planning, investment, and intervention over many decades.

From the 1950s engineers and planners took the city’s fairly organic Victorian street network, that filtered lazily out into the surrounding Isthmus, ripped out the Edwardian electric tramway, and imposed the extremely severe city containment of the motorway ring we know so well today. They then reordered almost every city street to serve the traffic that these motorways delivered. This is the city we now have.

It’s striking how disorienting it is looking at a pre-motorway map of Auckland, like this one from 1959, the year the Harbour Bridge was completed; the pre-motorway city. To our eyes now the southern edge of the city has no, well, edge, it just isn’t there:

This process that led to this is well documented and can be followed via these major steps:

1965 De Leuw Cather Report Highways

1965 De Leuw Cather Report Rapid Transit (unbuilt)

1971 Central Area Proposals (Section 1, Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6, Section 7, Section 8, Section 9)

1972 Auckland Rapid Transit (unbuilt)

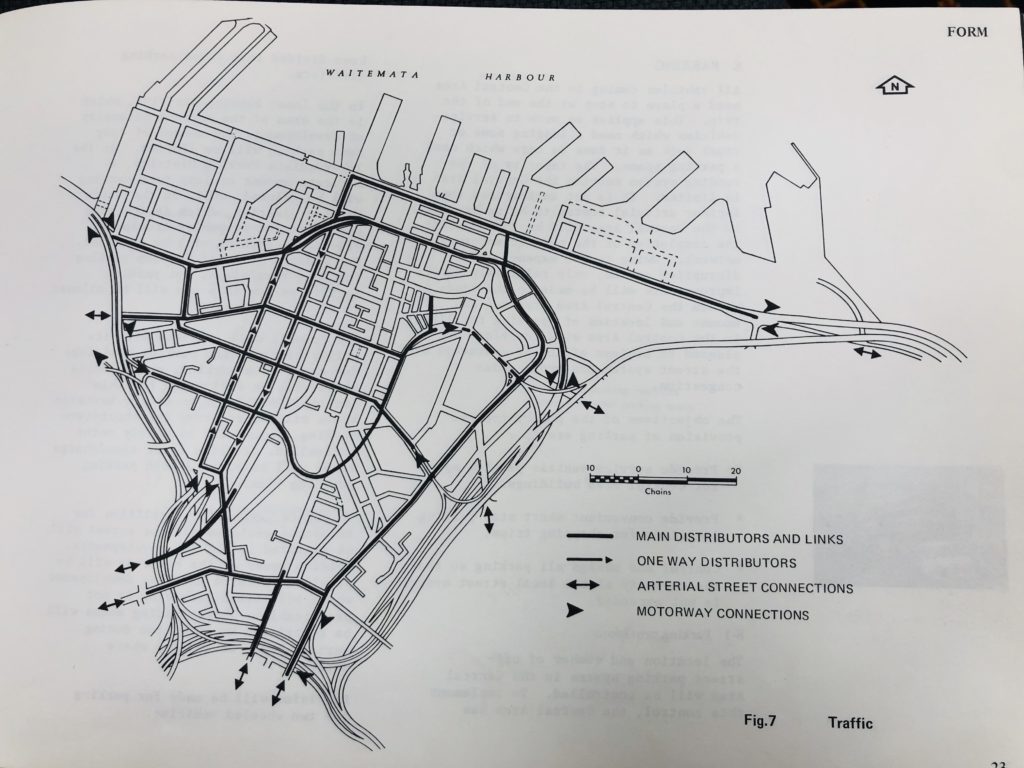

The 1955 Master Plan began the whole motorway programme, it was refined by De Leuw Cather a decade later, and the 1971 CAP report describes the consequential response in the city centre streets. The failure to fund and build either of the two rapid transit plans or anything like them, had a huge bearing on the pressure to fit buses into city centre streets, but it’s important to be clear that they still planned this car dominated city centre regardless. Here is the 1971 CAP street priority plan, which was still anticipating underground rapid transit to follow:

It’s clear to see how the tight noose of the motorway ring contains a city centre so small, and so constricted, that the off ramps from one side turn into the on-ramps on the other, without filtering down to city scaled lanes between. There’s barely any space for ‘city’ at all. This is city as off-ramp, rather than city served by off-ramps. All the streets shown in black above were considered primarily as conduits for the motorway system and not local access urban streets in their own right. Especially the direct on/off-ramps, but this ‘motorway serving’ condition is also continued through the very centre of the city on every major street too.

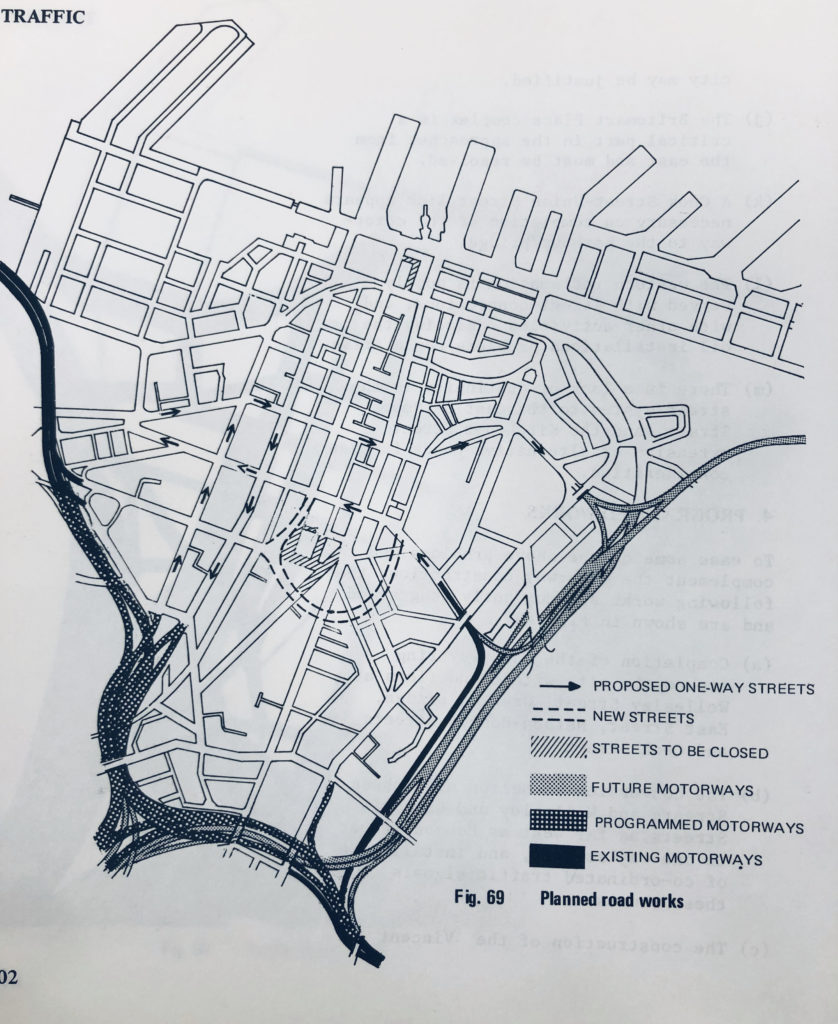

Additionally two big one-way couplets were planned: the north/south Hobson/Nelson one which we have long had, but also an east/west Wellesley/Victoria one including Kitchener/Bowen/Waterloo Quadrant. Of which only Kitchener was made one-way. The plan was to tunnel Waterloo Quadrant to Bowen to make an underground on-ramp for the Grafton Gully Motorway to match the Symonds St off-ramp underpass we all know at Wellesley St East. Thankfully the full circuit never happened. That truly would have made for a crazy car-go-round.

Though in late 1980s in an act of supreme Council mandated vandalism the lovely ‘Parisian’ lanes east of High St were demolished in order to straighten out Fields Lane to create the meaningless little stub clearly visible on the map above, designed to feed this drive-only plan. Mayoral Drive was forced through those city blocks to create the ‘distributor’ to link west to east so there was no point in the Queen St valley that a motorist couldn’t drive across.

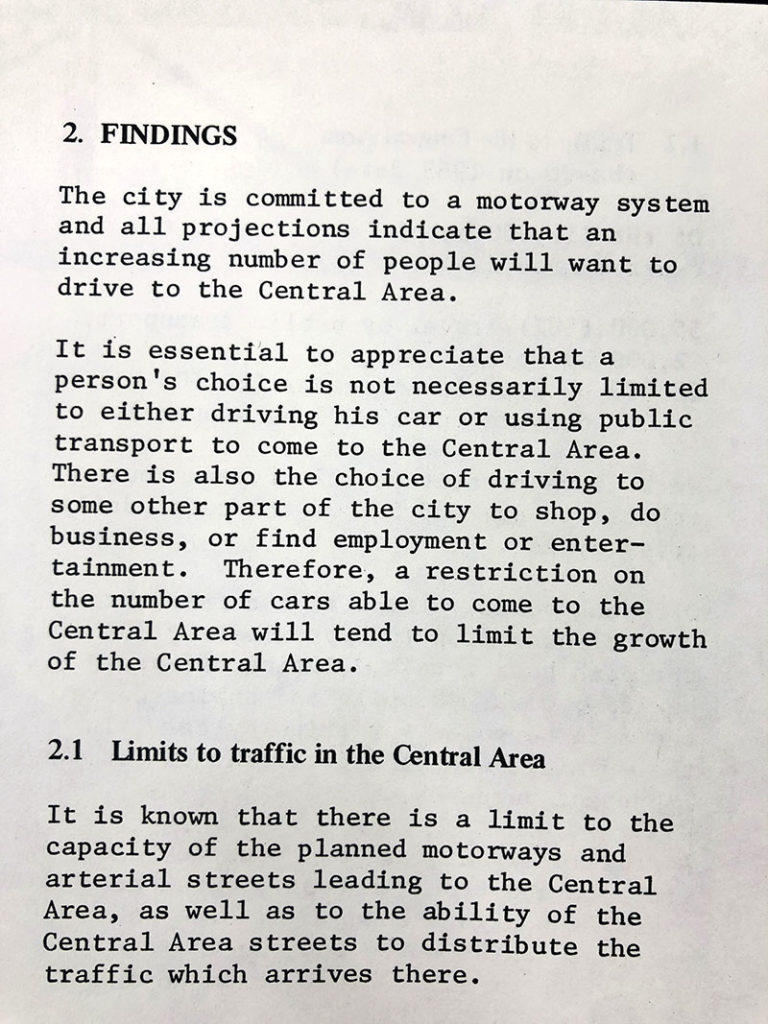

This is what was done to the city centre directly as a result of that multi decade commitment a one mode transport policy. The motorways were directed and funded by the National Roads Board (the precursor to NZTA) and Auckland City Council and the other Councils had to just deal with the consequences of this policy, the building destruction, the severance, and, especially the flood of cars (and the loss of rateable property and therefore city income). But then, as this passage from the 1971 Central Area Proposals makes clear, it is not a case of the planners disagreeing with the engineers, everyone pretty much agreed that:

- The car flood was coming, and

- Without it the city would die, cos

- No one wants to use PT (which we aren’t building).

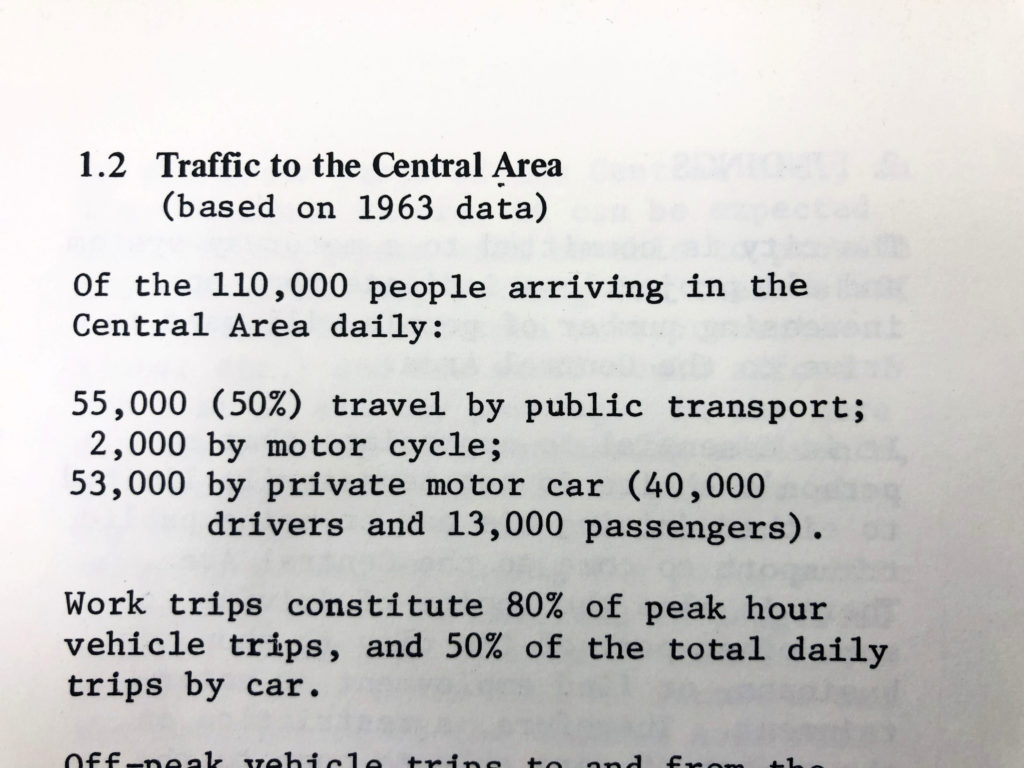

Yet they knew that the city already relied on public transit to function, they had the data:

Essentially they set out to dismantle this city and replace it with a car only one, accepting that it would wither, extraordinarily, in the name of dispersal. And wither it did. Public Transport ridership reached a nadir in 1994, with only 20% of people arriving in the am peak using the sorry PT services that survived the privatisation of the bus system, the decline of rail services and of course the removal of the trams. They also knew the costs:

The costs were on pedestrians, of course, which is to say the quality of the city streets for people, and precisely at the places where there is the ‘greatest numbers’ of them. But this was an anti-urban age, so the impulse here was to move the university out of town, and otherwise disperse economic activity, and get people off the streets. It’s all kind of mad; for of course without people there is no city. This period seemed to suffer from a collective amnesia about the purpose and form of cities throughout time. A kind if ‘this time it’s different’ all because of the private car.

These costs are however what transport economists like to call ‘externalities’, something external to the project, that is when they bother to count them at all. I would call them direct outcomes, and consider it entirely fraudulent to not count them against the value of the transport plan.

And we are only just now getting to grips with fixing this, much is currently being made of the fact that PT and Active journeys to the city centre in the am peak have now overtaken car journeys. Basically we have got back to 1963 (see above). We are still yet to undo the damage done to the city centre in the postwar era.

It is extraordinary what they were prepared to do in the name of progress after the war, literally moving whole hillsides and cemeteries, filling harbour bays, and flattening city blocks, as if there was nothing there before. Or rather they afforded themselves this; demanded the right to smash and grab pretty much anything, in order to get to a blank slate; the great desiderata of modernist planning; the bomb flattened city. The fresh start, the tabula rasa.

Such a radical and violent shift to impose on a city. Parts of the city, like Newton and Grafton Gullies faced erasure on the scale more like that of a natural disaster or carpet bombing. And others, like Karanghape Rd, then the city’s premier shopping district, had their entire economic basis pulled out from under them, condemning them to a near terminal decline. This was an extraordinarily bold change, imposed top down by public engineers and planners, with rather predictable outcomes. British engineer and planner Colin Buchanan said in 1966 the traffic in Auckland already made the central city ‘unpleasant, almost to the point of being uncivilised’, but on it marched.

So the great news is we now have the opportunity to fix much of this, and it doesn’t require destroying whole places, ruining the ecology of urban gullies, or severing communities from the city. This revolution is way gentler. Access For Everyone seeks to work with the radical change carried out in the modernist era, not upend it. Ameliorate its hard edges, its fixable failures; the city will still be served by motorway off ramps, but no longer be so dominated by them. It’s small but significant move is to return city streets, particularly in the core Queen St valley, to being more about people and place and not merely vehicle rat-runs. Vehicles that remain will be because they have direct business there, not because they are on the way to somewhere else, over the other side.

Drivers will be be able to get into town, but not across it. Instead more people will take advantage of better public transport services, new more spatially efficient micro and electric vehicle technologies, and we will have way better streets for that most powerful of urban modes: walking, to enable the city to flourish on the power of the timeless urban resource of; he tangata, he tangata, he tangata.

People.

Processing...

Processing...

Let’s hope there’s enough resolve to actually implement this in face of the opposition that’s going to mount against it. We should remember that High St is still car-centric, after all those attempts to make it better, that Hobson is still a gigantic (5 lanes!) car park of unidirectional traffic each afternoon.

I hope so too, it all hinges on whether Auckland Transport can escape from its current malaise and firstly actually starts implementing all the plans that it keeps delaying and re-reviewing, especially the many cycleways of which most were planned to be completed by now, and becomes more bold in scaling down the roads/intersections around the city that currently act to make walking difficult and unpleasant.

Even back in the early 1970s there were people in the Ministry of Works and Wellington who were envisaging a ‘leap forward’ to a more people oriented Wellington rather than the car oriented city which was evolving. But they had difficulty overcoming the status quo bias amongst the public and politicians… So NZ didn’t learn from overseas car oriented mistakes that even back then was apparent. NZ wasted 50 years of what could have been positive incremental city-building development.

Check out the video about Wellington from 1971 in this article.

https://talkwellington.org.nz/2019/can-an-eco-city-solve-wellingtons-housing-crisis-part-one/

Question; Under the proposed “Access for Everyone” scheme how would traffic in the Wynyard Quarter access the southern motorway without using Hobson St?

Union and Pitt?

Nelson Street will be the main connector. The use of Union Street at the moment for rat running is inappropriate.

I’ve not seen anything to suggest that Hobson Street would not be available. It appears that it will just be scaled back to an appropriate width for the location.

When I read ‘The Auckland city centre street network is, at last, about to undergo some proper change. ‘

A4E was announced in November and it is now April, we were told there would be tests for this throughout the year, nut I haven’t seen anything. Hard not to start getting disheartened when literally anything ‘good’ for the City seems to be lacking any tangible progress.

It’s not like we even need to construct anything for this so you’d expect quicker timeframes…

I think a subtext of the post is that while A4E is a subtle and cheap change, especially compared to the ‘heroic’ scale of the one it tries to ameliorate, it still is an massive shift in strategy, so will be contested by all the forces of the status quo… so will take time and effort.

Proposals supposed to go out now-ish with planning committee I thought, and 6 months of consultation to follow.

AT strategy doesn’t see it happening until a massive increase in PT capacity is provided (for which they have no plans beyond CRL and Light rail circa 2030), so don’t count on this happening without a fight.

I am way more optimistic about the speed of change.

https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2019/03/14/486488/city-air-pollution-still-too-high

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12155503

These are just a couple of the articles written about Lower Queen St – or the money end of the city.

Can you imagine that the developers of Auckland’s Commercial Bay will tolerate shoppers being discouraged by potentially poor health outcomes from shopping there?

Even more, can you imagine the Mayor, who didn’t want bits of light rail track spoiling pre publicity shoots for the America’s Cup seeing instead photos of shoppers, or cruise ship passengers wearing face masks as they quickly traverse the area?

This shows why it will take a real effort to get from where we are to A4E. The motorway occupies the space required for a real “ring road” (which should be U-shaped, from waterfront round to waterfront), providing access from north south east and west to each destination cell. For example Wynyard Quarter: go to Onewa Road, and come over the Harbour Bridge….

Please discuss.

Nelson and Mayoral drive will be the main inner connectors on the west and south side to compensate for the stupid arrangements with the motorway onramps and offramps

Patrick have you seen the ‘Report on the Buchanan Report’ by the city engineer in July 1966, it’s upstairs at the city centre library. https://discover.elgar.govt.nz/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1484773

Reading it after the Buchanan report just shows their lack of imagination/intention to deal with the concerns raised, concluding There Is No Alternative, and obviously they did not retain his services to expand analysis/solution past that excellent initial assessment.

Thanks, will chase. Sadly we still get a great deal of TINA from the unimaginative…

You can’t assume they could have made any choice and it would have worked. The politicians running the old Auckland City Council faced competing threats from other cities and boroughs, not just Manukau and Takapuna but also places like Newmarket Borough (who eventually won on retail). They were trying to give the CBD a future at a time when people wanted to drive. So the plan was to have the motorways close to the CBD and build a ton of parking. If they hadn’t then where ever the motorways had gone would have been a better place to put offices and the CBD would have had thirty years of decay. On the plus side we would have a cool little heritage centre now and we would have avoided development during a particularly shitty period in architecture.

I agree, that’s what I say; was the zeitgeist. Not arguing we try to change history, but rather we have no use for this ugly and dysfunctional model today.

Funny though. The parking retail model didn’t really work either did it? Count how many department stores AKL had, and note all, every single one, Farmers, George Courts, Milne and Choice, all the others, got multi-storey carparking buildings built for them by council….

Except one, only one didn’t. And guess what. That’s the only one we still have today: Smith and Caugheys.

I don’t think not having a carpark built for them is what kept Smith and Caugheys but I take your point that it didn’t save the others in the CBD. Destination retail in the centre was always going to be challenged by malls. Maybe Smith and Caughey customers don’t like mixing with the rest of us.

Regardless the old Auckland City Council did a great job of keeping the CBD as a major office area and they gave the rapid rail thing a good go despite nobody else wanting it or being prepared to pay for it.

The question is without the motorway ring, and without motorways, and without the sprawl that allowed, how big would Tauranga be now, and would we have enjoyed living there?

Correlation, darling, correlation. Point is the competitive advantage city centre retailers have is not driving access… no point in trying to compete on this with dreary suburban tarmac oriented malls. To try is to lose. This attempt was a bust. Watch CHCH city centre loose trying it now, they are, it seems, having their 1960s now…. so it goes.

Yes, like the correlation between CPR and death, both are caused by something else.

I’m not sure it’s accurate to say that this was a period in which people “wanted to drive”. They basically had any other choice systematically taken away from them.

Yep. That’s what I show above. Not only were driving and city dispersal prioritised; they got almost every public penny to force their uptake. And alternatives, especially public transport, but also something as simple as walking on a city street were systematically obstructed. And for decades, by both central and local govt. a sort of institutional psychosis…

A few vanishingly tiny moments of relief from this, like the pedestrianisation of Vulcan Lane, or the botched blocking of Lower Queen St, complete with carparking…

“we would have a cool little heritage centre…”

The implication that this would be a good thing tells a lot about modern architecture, none of it good.

Let’s see if we can find a pattern. SkyCity complex. Blank wall on 2 sides. Cop station. Blank wall. Your average apartment building. Blank wall. Aotea Square. Blank wall left. Blank wall right.

In a few years that new SkyCity block is finished, and we’ll see if we escaped that particularly shitty time.

I don’t think blank walls are a symptom of modern architecture, rather a symptom of our planning rules and Volcanic Viewshafts etc etc.

There’s a flaw in your interpretation of history.

Before the city was reorientated around the car, PT usage was higher, not lower, than today. Yet the city was low-rise.

After the car became king, the city grew to what you see today.

It’s time now to reorientate again into a combination of the two. The high-rise city that the car enabled, but with the more convenient PT links to outer suburbs that until now only the car has provided.

It’s also worth mentioning that car growth really took off from the 1980s, well after the decline of PT usage got underway. That’s because NZ removed all car tariffs and flooded the market with near-new cheap japanese car imports. Something that continues unabated in 2019, leaving us with one of the cheapest car buying markets on the planet. Cars that cost $20,000 in Australia or the US cost $9,000 here.

It’s almost like not having a dying industry sucking up taxpayer dollars for jobs they’re going to lay off anyway means you don’t need massive import tariffs on vehicles…

The CBD was lower rise than it is today, however the residential suburbs were more dense than they are now, which is a key to successful PT. Providing lower density sprawling housing requires with PT requires a higher subsidy, which based on previous comments is something you are against.

The suburbs were also not so far away then. This is a huge and never ending cost burden of sprawl; the massive increase in distance between everything. And cost for cities who then try to fix the many problems of sprawl by retro fitting transit service to serve them as driving coagulates…

‘Before the city was reorientated around the car, PT usage was higher, not lower, than today.’

Did you actually read the post, Geoff? Yes that’s what I say.

‘Yet the city was low-rise.’ Building occupancy was much much higher then, so city density was higher despite built density being lower. Places like Ponsonby had building occupancy levels that we still see today in places like Mangere.

The city was not low rise, it was mid rise. Very dense, more dense that many high rise areas.

High rise is, in part, a reaction to using the land for roads, motorways and parking. If you use up a big chunk of your area for non-productive uses, your productive buildings need to be taller to get the same amount of people in the same area.

Conversely, if you don’t waste so much land on roads and parking, you can have a more compact and dense city without having to go tall.

Personally, I like cities that have in the main, buildings under a max of seven stories. They seem to provide good density and still allow reasonable sunshine to penetrate to the streets. Excessively tall buildings without a reasonable distance from their neighbour produce shadowed canyons and are thus unpleasant places in which to spend much time.

I fear Auckland is allowing too many very high buildings. And furthermore I am not sure of the wisdom of 4 or 5 stories of parking from ground level before the commencement of office or apartment occupancy.

Fully agree; give me Barcelona over Beijing any day. But as Nick points out above it is a direct function of both our widespread low height limits and spatially inefficient autodependency, that we end up instead with a small area of 50 storey buildings instead of a bigger area of 5 storey ones….

“It’s also worth mentioning that car growth really took off from the 1980s, well after the decline of PT usage got underway.”

I think that’s when many households started to have 2 cars. Do you know something to help tie together the two parts of that first graph in the following post? It looks to me like car ownership took off about 1051.

https://www.greaterauckland.org.nz/2013/11/27/more-details-on-vehicle-ownership-over-time/

Ha! *1951*

Yes, because of course no city where the vast majority of people access the city by public transport hve high rises. Well except New York. And Paris. And London. And Sydney.

But otherwise…

I support the cell proposal – I hope it proceeds

1) removes through traffic

2) reduces delays and emissions

3) more active mode friendly

4) needs a parking building in each cell

5) needs a two way high frequency shuttle between cells

6) Could allow fully protected movements (incl ped/cycle) at CBD traffic signals with the reduced traffic demands.

Australian budget – $500m for park-and-ride, $100m for “threatened species and cleaning up waterways and waste”. o world.

Someone needs to tie this post to Matt’s post today.

This whole A4E plan hinges on Queen Street.

Queen Street can’t have a settled future until light rail is settled.

Light currently contests between NZTA and NZSuperfund, and there’s no clear decision out of the papers going up.

Light rail is on life support right now. There’s almost no-one in the team. There’s no confirmed route. AT and AC are shut out. The government has not stepped in to support NZTA with its decision despite NZSuper actively undermining it with their own proposal.

The government are about to further upend NZTA with a raft of reports and structural changes anyway. Because light rail as an operating system is now over a decade away, there’s no settled future for Queen Street.

The spatial successes to be had are those underway well before A4E started to become the new de Leuw Cather report.

The successes are Wynyard block, CRL corridor, and Quay Street.

Queen Street is, as ever, a decade away.

I don’t see the problem. We could close Queen Street to traffic tomorrow, just run buses or maybe nothing at all.

That’s doesn’t preclude, or require, light rail or anything else. In fact it probably makes it a little easier.

I’m just guessing you don’t use a car or a bus that uses Queen Street …

…or a taxi or any emergency service that uses Queen Street …

or are involved in any business within or connected to Queen Street.

Queen Street is ruled from Willis Street.

– I’m just guessing you don’t use a car or a bus that uses Queen Street

He already stated continue buses down Queen Street.

– …or a taxi or any emergency service that uses Queen Street …

No need for Taxis on Queen Streey, they like other cars would have access to other streets. Of course Emergency would be allowed.

-or are involved in any business within or connected to Queen Street.

Because there is ample parking on Queen St? Because the majority of shoppers park on Queen St? Where are you getting your info from?

Great post. We sure need to keep undoing the mistakes of the the motor car dominated city degeneration. Oh sorry, “generation”.