Note: this 6-part series is now complete; here are parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. I suggest reading on a desktop, as the screenshots of the pages should be large enough to read (hopefully).

In 2013 or thereabouts, I bought a book from a second hand bookstore in Tirau. Published in 1985, it takes a look at what cities will look like in the distant future: the year 2000. Tune in over the next few weeks, and I’ll take you through it.

As you’ll probably guess from the cover, it’s a children’s book, so 15 years into the future would have seemed pretty far away. Kids’ books obviously use simpler language, and might get a little distracted looking at cool machines, but on the other hand children are more inquisitive and open to new ideas. In 1985, this book was probably read by some pretty smart kids.

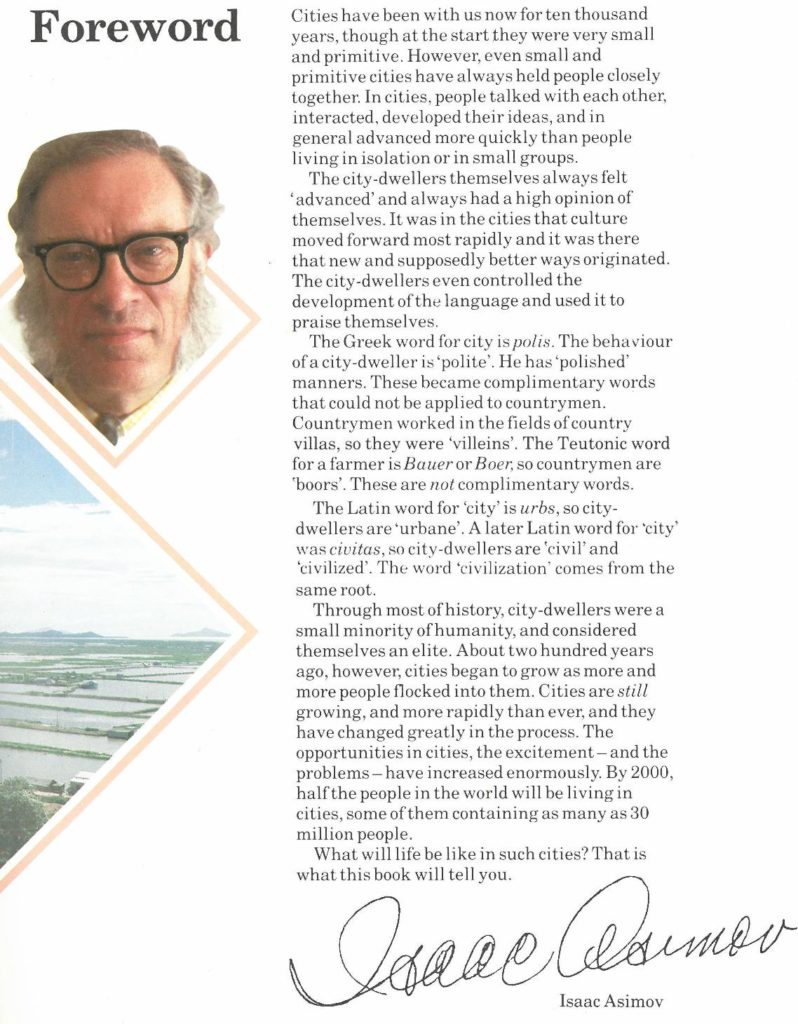

The book, simply called “Cities”, is part of a series called “Your World 2000”, edited by one of the greats of 20th century science fiction, Isaac Asimov. So what does this lauded author and thinker have to say about cities?

Not much, apparently; Asimov seems to have only written the foreword. But the book achieves a certain gravitas by association with him, and his impressive sideburns.

The listed author is Robert Royston, who I can’t seem to find anything about, and the consultant was David Satterthwaite, who has been at the International Institute for Environment and Development since 1974 and is still there today – a bloody good innings. David’s expertise on cities has only increased since this 1985 book; he’s researched urban poverty and environmental issues, and contributed to the last three Assessment reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

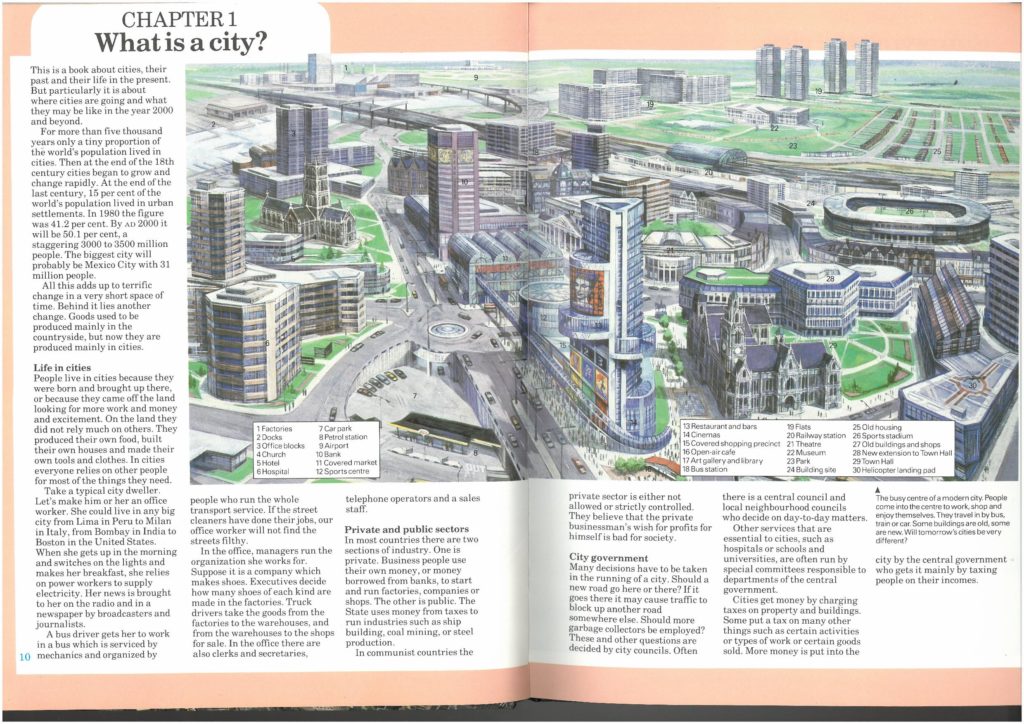

CHAPTER 1 – WHAT IS A CITY?

“For more than five thousand years only a tiny proportion of the world’s population lived in cities. Then at the end of the 18th century cities began to grow and change rapidly. At the end of the [19th] century, 15 per cent of the world’s population lived in urban settlements. In 1980 the figure was 41.2 per cent. By AD 2000 it will be 50.1 per cent”.

The world’s urban population, and the percentage of people living in cities, has continued to increase. According to the UN, it actually took until 2007 for that percentage to tip over 50%, and it has now reached 54%.

The definition of a city varies between countries, so these numbers should probably be taken with a grain of salt – and it’s arguable whether these global figures are meaningful, given the many different types of city (not to mention the many different types of ‘rural area’). In New Zealand, we’ve long been an urban nation; 85% of Kiwis live in an “urban area”, a town or city with a population of at least 1,000. More than 70% of us live in a “major urban area”.

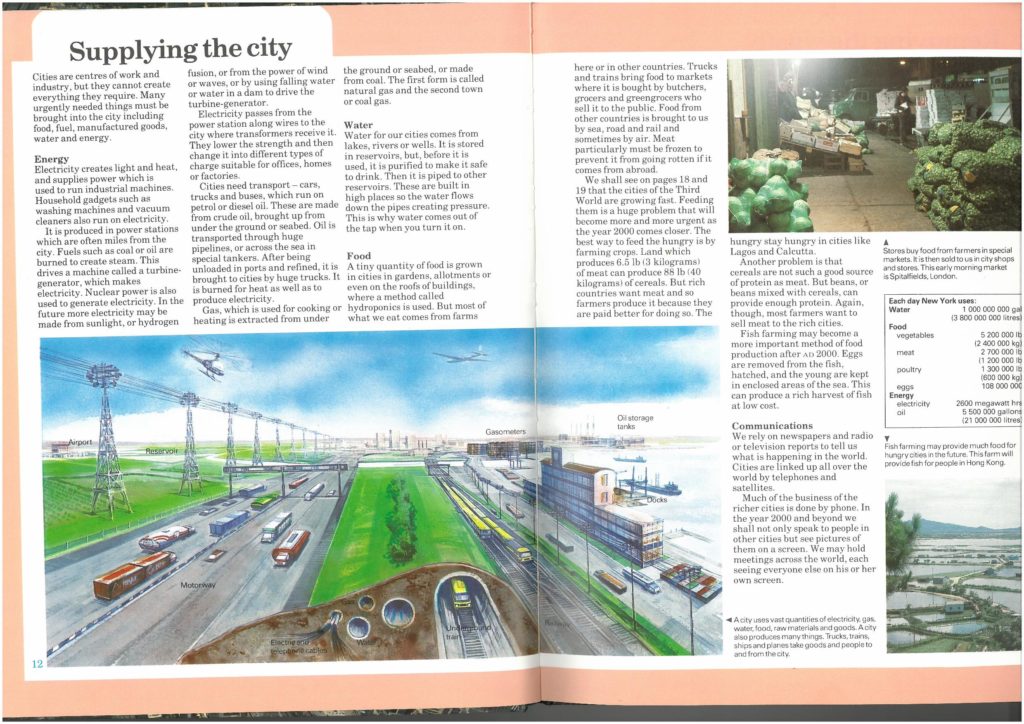

This page makes the point that cities rely on trade with other areas for things like energy, water, food and communications.

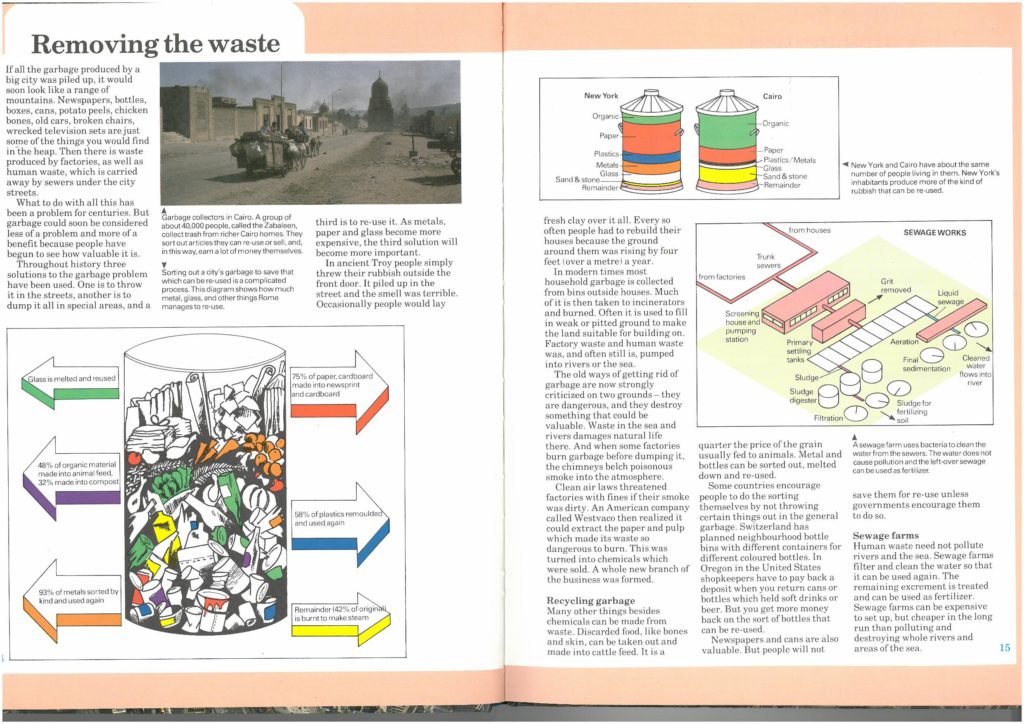

These pages give a good quick history of urban waste, which remains an important issue today. It’s not something I know much about, but I’ve enjoyed learning more in recent media coverage – despite our mental image of ourselves as clean and green, New Zealand has been left behind in terms of how we deal with waste; Aucklanders discard a lot of stuff that could be composted or recycled; and we rely on other countries to recycle our paper and plastics for us. “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” seems as relevant as ever, and maybe “Compost” is important enough on its own to be a fourth word there.

Processing...

Processing...

i dont really consider less than 100k in an urban area as a city, more a large town.

Jermaine Clement has aged a bit..

What about Jemaine Clement? How’s he doing?

I thought that he looks like the father of Clive Matthew Wilson, of Dog and Lemon fame.

“In ancient Troy people simply threw their rubbish outside their front door. It piled up in the street and the smell was terrible. Occasionally people would throw fresh clay over it. Every so often people had to rebuild their houses because the ground around them was rising by four feet (over a metre) a year.”

I wouldn’t have thought they’d have produced that much waste. It’s quite a lot of soil building. Maybe we should learn from them, in order to sequester some carbon. And have tiny houses that move around from spot to spot, forever climbing higher.

Interesting read, thanks John.

I like that example in the artist’s impression of a shallow-cut+roof-over+landscape rail tunnel. This would be extremely cheap to do, compared with the cost of mined-tunnels or full-depth cut-and-cover. We could be doing a lot more of this where conditions permit (such as along Wellington’s waterfront).

Cut and cover tunneling will not happen in Wellington unless somebody has an open cheque book with endless money supply. The reason is the city centre is to compact and will cause massive disruption to the city and its infrastructure. Just look at what is happening in Auckland with CRL where ‘cut n cover’ tunneling is being used in regards to infrastructural, foot and road disruptions.

Kris, from your repeated sniping at this idea I wonder if you actively *don’t want it to happen* (Wellington heavy rail extension), rather than just believing that it won’t. I am not proposing “cut and cover tunnelling” along the waterfront, but a much cheaper variant I call “lower and box-over”, where even the “lowering” part is optional. To happen on the waterfront would mean re-purposing this away from being a main traffic artery, but doing this has been in various aspirational plans for some time now anyway. The disruption during construcution is not a reason to shy away from a project if it is worthwhile (like the CRL). It needs to be managed just as it has to be for major urban road construction (e.g. when the Arras Tunnel was built).

If you have a personal objection to extension of heavy rail rather than simply doubting the achievability of it, I would be interested to what your objection is.