This is part 4 of a 6-part series covering “Cities in the Year 2000”, a kids’ book on cities published in 1985. Here are parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. I suggest reading on a desktop, as the screenshots of the pages should be large enough to read (hopefully).

The first page talks about skyscrapers: their origins in mid-20th-century New York, and how they are built. “At first, [Americans] did not like living one on top of the other in these new apartments. New Yorkers finally accepted life in apartments when they realized they were not very different from hotels”. Probably some oversimplification there, I’m sure Patrick could tell us more!

Overseas (and to a small extent in New Zealand), high-rise apartments have been built as social housing, and they haven’t always lived up to expectation:

The skyscrapers would be a good distance from each other and would be set in gardens for people to look down on or stroll in… [but] tenants felt cut off from the world outside… the sense of living in a community of neighbours was destroyed.

This led to crime, greater social isolation, and damage to buildings. Many of them have now been demolished and redeveloped, using the learnings from the first time around.

“The lowrise housing estate… has been much more successful. Apartments are in buildings a few storeys high at most. These are arranged around an open space… [where] parents can keep an eye on children playing”. Importantly, “the surroundings are more friendly and personal. This solution fits the same number of people into the same area as the old highrise did”.

It’s not mentioned here, but it’s also considered better to mix social housing in with private/ market housing: “pepper potting” to give better social integration. John Key wasn’t a big fan of it, calling the idea of social housing in Hobsonville Point “economic vandalism”, but it’s widely established elsewhere.

As for other low-rise buildings, houses and the like, the book notes that they can look very different depending on where in the world you are. In New Zealand, our houses are usually good ol’ wood, but elsewhere you’d be talking brick, stone, or mud in poorer countries.

Much of what is shown here is equally applicable today. The key point is that “existing houses can be made more efficient and new houses can be specially designed to hold heat in and re-use it time and again”.

Interventions include: insulating hot water tanks; insulating roofs, ceilings and floors; double or triple glazing windows; heat pumps; solar panels or hot water pipes; and so on.

Another sobering fact is that New Zealand homes, even the new ones, tend to have much worse energy efficiency than those overseas. Really, we’re building yesterday’s homes, and many other countries, especially European ones, have already moved on.

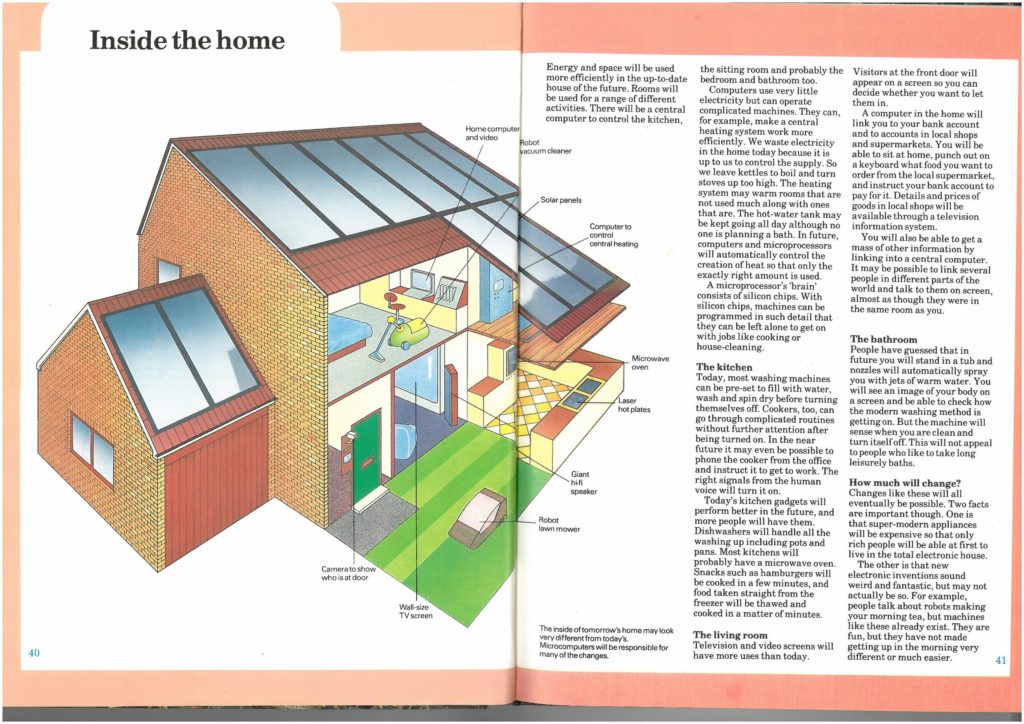

This one’s for the kids. A bit of imagining around what robots, smart tech etc could be inside homes. We have indeed developed robot vacuum cleaners, often ridden by cats in shark costumes, although I’m not sure how much use they really are in two-storey homes (they can’t really do stairs). Most of the other things in this picture are either available or on the horizon, and of course we now have new fantasies about what the home of the future will look like.

Processing...

Processing...

The Inside The Home page is amazingly accurate (although I’m not sure I want a computer regulating my shower duration).

We have a valve that just turns off the hot water. Generally reduces the shower time but does need active management. 🙂

“The machine will sense when you are clean and turn itself off…” well well well. A long android finger dipping itself in the luke-warm bath water and prodding you to see if you still have residual non-organic substances coating your outer skin…. Mmmm, nice….

I would disagree high rise apartment is a failure and we should go to low raise.

The issue is not about high raise or low raise, it is about a high concentration of poor, criminal, and anti social people.

The same issue allow happen on low raise – like a run down slump in Brazil.

In fact, the same issue would not happen on apartments that house rich people. For example the high raise luxury apartments with sea views (like in gold coast) would be very desirable to live in and has none of the social issues.

Rich suburbs have the same level of criminals, Kelvin. They’re just corporate criminals and environmental criminals instead of petty criminals. People are good and bad everywhere.

But at least we personally feel safe as they won’t rob us on the street, or graffiti our walls.

I’ve been in an upmarket hotel/apartment high-rise development where the permanent tenants were quite fearful for my visiting children. The children wanted to get out of the apartment, but the tenants didn’t want them to play in the corridor – not because of noise for other tenants but because the sound insulation was so good that we wouldn’t be able to hear them ‘if they disappeared, where would you start looking? Which apartment could they have been pulled into?”

Safety comes from community, it’s not something fundamental to the highrise form.

Bollocks Heidi. Yes there are some criminals as you mention but in general the rates of crime are much lower – especially violent crime.

There are a variety of social and economic reasons for the differences.

🙂 Was I stirring? Truth is we don’t know how much white collar crime is happening around us. This article’s reasonably interesting: http://criminology.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264079-e-267

“It is estimated that approximately 36% of businesses (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016) and approximately 25% of households (NW3C, 2010) have been victims of white-collar crimes in recent years, compared to an 8% and 1.1% prevalence rate of traditional property and violent crime, respectively (Truman & Langton, 2015).”

Perceptions of comfort and safety are different for everyone. I guess most people are afraid of the boogie man. But those who have been victims of white collar crime may feel most uncomfortable in white collar areas?

And then there’s the statistics about where traffic violence is happening most, which is probably what we should be most wary of… Am I stirring again? 🙂

The Tomorrow’s Houses page gets quite a lot right, but it also shows what technology we’ve had available and haven’t used, eg heat transfer from warm air (or water) leaving the house to the cool air (or water) entering it. And it correctly mentions the need for good ventilation if the house is designed to trap heat. I’m seeing way too much use of heat pump cooling systems instead of passive ventilation – another example of Jevon’s paradox, I suppose. The problem is most marked in apartments but not limited to them.

The Low-rise, high-density section describes this form only in terms of its best example – perimeter block housing. Unfortunately, this isn’t a form that our unitary plan establishes; a problem that needs to be corrected before the plan creates more driveway-heavy sausage developments.

The pages do get to the kernel of the advantages of low-rise over high-rise: in high-rise “skyscrapers… tenants felt cut off from the world outside” whereas in low-rise: “looking out of the window, parents can keep an eye on children playing” and “windows on the other side of the estate look out onto the street”.

This is explored further in the Pattern Language “Four Story Limit”, which I urge people to read if they haven’t already. It starts “There is abundant evidence to show that high buildings make people crazy”… and cites the research, “Fanning shows a direct correlation between incidence of mental disorder and the height of people’s apartments.” Surprise, surprise, there is a gender difference, research which anyone promoting high-rise development should use to temper their enthusiasm: “the correlation was strongest for women… and it was weakest for men”.

The research about children is convincing: “The percentage of young children playing out of doors on their own decreases with the height of their homes… Young children in the high blocks have fewer contacts with playmates than those in the low blocks.”

Some of the reasons are explored: “At three of four stories you can still walk comfortably down to the street, and from a window you can still feel part of the street scene… Above four stories these connections break down. The visual detail is lost; people speak of the scene below as if it were a game, from which they are completely detached.”

Interesting that thanks Heidi.