This is a guest post by Brendon Harre. It’s the third part of a post about Christchurch, it’s history, and what needs to change to fix it’s transport woes and this part has been published on Brendon’s medium.

You can read part one here and part two here.

Transition era where modernisation of Christchurch’s multi-modal transport system stopped — the 1930s

To achieve a low-carbon future in New Zealand, some people have argued we should look to the past. The country once had thriving towns and cities with multi-modal transport systems, yet we have largely turned our back on this history. This is especially true for Christchurch, where there appears to be little institutional memory of its multi-modal transport past.

In his groundbreaking study Lost City: Forgotten Plans for an Alternative Auckland, urban historian Chris Harris dates the turning point to 1950. Both major political parties now agree it was a historic, generational mistake not building ‘Robbie’s Rail’ in the 1970s. A consensus has emerged that Auckland is now paying the price for underinvesting in multi-modal transport systems post-WW2.

Business journalist Bernard Hickey dates the turning point to 1989 for provincial New Zealand in his article The answer to NZ’s transport future lies down a long tunnel in Whanganui. Until they were wrecked in the early 1990s, provincial cities had thriving public transport systems, Hickey contends. Car ownership was less than 300 per 1000 people until the 1970s (it is now over 900 in Canterbury). The Public Finance Act and the Reserve Bank Act changed this, Hickey argues. The driving forces behind this reforming period were to reduce government debt, cut taxes and make users pay for as many public services as possible, including public transport.

As a side note the ideology of users pay thinking was that passengers should pay for the full cost of public transport services. ‘Users’ did not include all beneficiaries from transport spending. For instance, it did not consider land-use effects as a part of the ‘users pay’ framework.

This report makes the case for the 1930s being the point when progressive improvement of Christchurch’s multi-modal transport system stopped.

The history of Christchurch compared to Wellington illustrates why this earlier date might be more accurate.

The two cities are a similar size (it was only in recent decades that Greater Christchurch pulled ahead). Despite their similar populations, they have very different spatial planning histories. This is important because urban development has a hysteresis aspect to it (hysteresis means the state of a system depends on its history). In other words, the past and pathway dependency are important parts of transport planning.

It was in the 1930s that the transport paths of Christchurch and Wellington began to deviate. The former took the spatial planning road to car dependency while the latter managed to keep multimodal pathways going — just.

Parliament made two key transport-related decisions that changed the future transport system make-up of Wellington compared to Christchurch.

First, there was the 13.5 km electrified and double-tracked Tawa Flat deviation, involving two tunnels of 1.2 km and 4.2 km in length. This project was approved by the Railways Authorisation Act in 1924, which meant it was paid for by central government. When it opened for passenger trains in 1937, the deviation reduced the travel time from Wellington to Porirua by 15 minutes. This has been further reduced to the current travel time of 21 minutes.

World-wide evidence shows being able to travel to a destination in under 30 minutes is valued by commuters; the improvements to the Wellington-Porirua line underpinned the success of rail in the capital.

Second, the Hutt Valley Lands Settlement Act of 1925 provided the legislative framework for the Petone-Waterloo line to be paid for by the betterment of the land it served (i.e. another land value capture mechanism). The Act set in motion the process that culminated in a double-tracked, electrified commuter railway through the Hutt Valley.

For Wellington, those Acts from the 1920s created a V-shaped linear spatial plan that extended Greater Wellington to Porirua and the Kapiti Coast in one direction and up the Hutt Valley in another. Without these spatial planning interventions, Greater Wellington would not have its current built form.

These V-shaped multi-modal transport corridors have had many flow-on effects, particularly the Wellington region’s much lower transport related greenhouse gas emission profile. It also included the First Labour Government’s successful house building programme in the Hutt Valley and Porirua where earlier government house building programmes in Petone had failed.

In the decade to 1947, New Zealand built social housing at a rate of 1.55 per thousand people. Today, that would equate to a state build rate of 7,750 homes per year — three times Kainga Ora’s output in the 2020’s.

However, the central government of the time didn’t replicate the successes of these Wellington multi-modal transport corridors in either Auckland or Christchurch.

In Australasia, the first electrified suburban rail service started in Melbourne in 1919. It was an immediate success, with patronage soaring because of quieter less smoky services, quicker travel times and more frequent, cheaper services. Sydney followed shortly after.

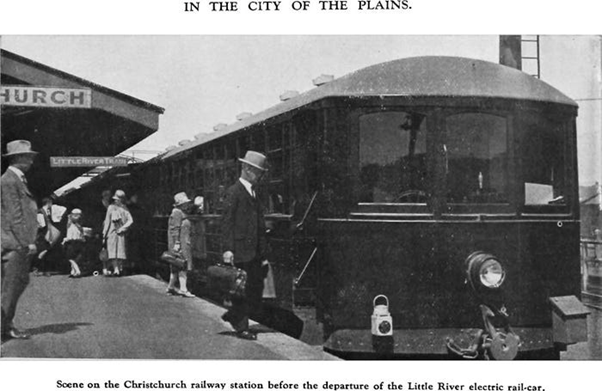

New Zealand’s first electrified suburban rail line was built in Christchurch in 1929 between Lyttelton and the city; its primary purpose was to better manage tunnel operations.

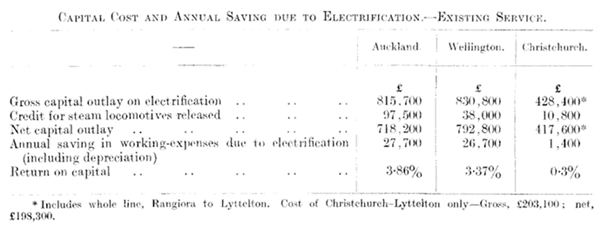

Parliament decided against electrifying the rest of Christchurch’s suburban rail network based on the recommendation of the 1925 Merz & McLellan report. While the cost to electrify Christchurch’s rail system was less than Auckland or Wellington, the estimated cost savings based on savings from coal usage were considered too small to justify the capital investment. Improving the network effect from better local transport infrastructure and the land-use effects of orientating urban development along rail corridors were not considered.

Greater Christchurch had one last shot at modernising its multi-modal transport system with electric battery trains.

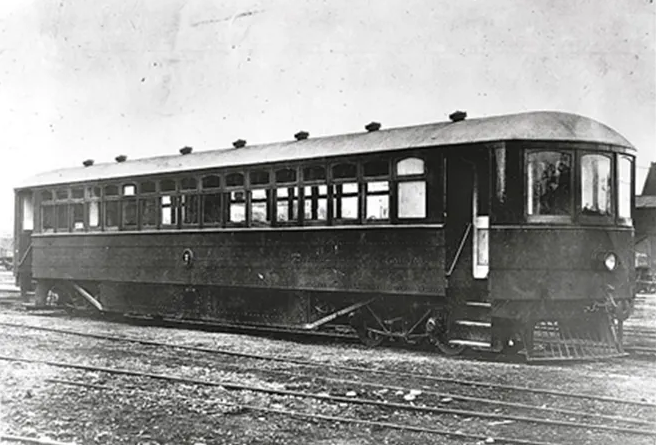

In the 1920s, NZ Railways experimented with several different railcars. The most successful was the Edison battery electric railcar, which ran between Christchurch and Little River via Lincoln for eight years through to 1934. The service, which had a travel time to Lincoln of about 25 minutes, received rave reviews and write-ups. Germany successfully used more powerful electric battery trains after WW2 and new electric battery trains are being produced today, proving the concept was viable.

Electric battery trains could have been a good option for Christchurch as a transition towards a fully electrified suburban rail service.

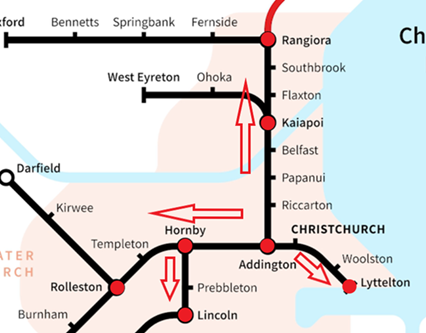

A modern commuter rail network bounded by Lincoln in the south, Rolleston in the south-west, Lyttelton in the south-east and Rangiora in the north was clearly possible.

Unfortunately, when the electric battery railcar was destroyed in a 1934 fire it was not replaced. This marked the final milestone of the rail era. From this point onwards, improvements stopped and as each piece of rail infrastructure reached the end of its economic life the service was closed.

The Lincoln line reverted back to steam engines after the 1934 fire. During the 1951 waterfront dispute, the resulting coal shortages meant that train services were stopped. They never started again.

The official reason for not replacing the battery electric train was the financial situation of the Great Depression, but Parliament had no problem funding the far more expensive Tawa deviation. Land value capture techniques could have been used to assist with funding. For whatever reason, Wellington was prioritised over Christchurch. Perhaps the capital needed more help, or maybe the politicians of the time thought Christchurch was a provincial town that should focus on freight exports. It’s hard to know. What’s more certain is the spatial planning consequences that followed these decisions. Christchurch with the partial exception of cycling had put all its transport eggs in the car dependency basket.

State Highway era — 1920s to Present

In Canterbury there was only a short overlap in the 1920s and 30s between the multi-modal transport era ending and the state highway era beginning.

In the 1920s, New Zealand’s central government took more control over the national road network. The Main Highways Act of 1924 created the Main Highways Board, which was given control of roughly 10,000 km of roads designated as main highways.

Central government initially contributed about 50% towards the Highway Board’s costs via funding mechanisms including petrol taxes, car registrations and mileage taxes (now called ‘road user charges’). Local authorities funded the remaining 50% from rates and driver licence fees, which they collected at the time. In 1936, central government began covering all the costs of main highways, which were renamed state highways.

At some point last century, the government further centralised control over the national road network by contributing 50% of the funding for local roads, too. The Main Highways Board has been renamed several times, it is now NZTA – Waka Kotahi.

This centralisation created a significant problem. Funding transport projects from road user charges and having this allocated by a central authority contributed to the disconnect between transport funding, project prioritisation, and local land use effects.

Christchurch in the second half of the 20th century is a clear example of this.

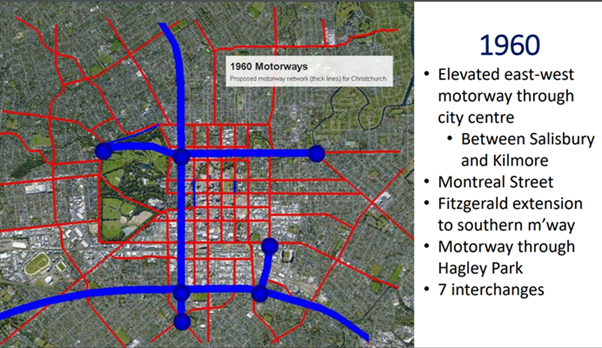

Central government proposed a regional spatial plan for the city including a series of motorways (in blue) connecting the north, south and port areas via the central city.

The motorway plan could have looked something like the Welsh example depicted in the image below.

Local Christchurch politicians campaigned against the intrusive plan because they believed the motorways would be a blight on the city, not a benefit.

Numerous motorway proposals were put forward, and eventually the northern and southern motorways were built — but well away from the city centre, unlike Auckland and Wellington.

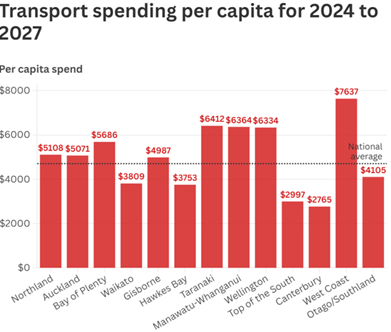

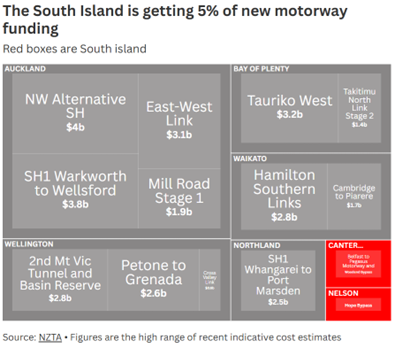

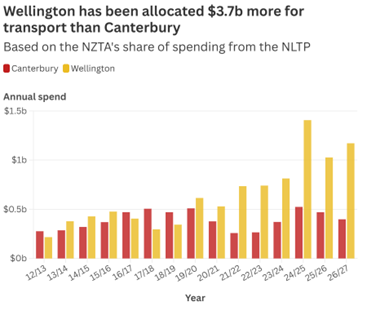

Maybe this opposition to the motorways explains the fact that, Canterbury receives about half the funding for transport projects compared to the amount it pays in vehicle taxes.

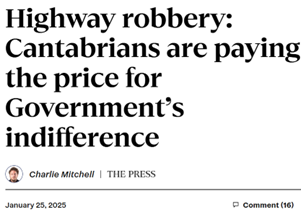

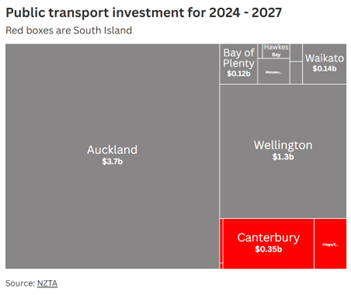

However we got here, it is undeniable that Canterbury’s transport needs are being ignored by central government agencies. An article by journalist Charlie Mitchell in a series of charts explains the situation.

Note the top of the South Island and Canterbury also received the least funding in the 2021 to 2024 period, too.

Canterbury’s transport history shows the state highway era, and its associated funding model hasn’t been good for Christchurch.

Charlie Mitchel notes in his Highway Robbery article that “If funding had matched its population share since 2021, Canterbury would have an additional $2.6b — enough for several motorways, a decade of local road maintenance, or most of a mass rapid transport (MRT) system.”

Charlie is not wrong to call Canterbury’s and the South Island transport funding “highway robbery”. In effect governments of both persuasions every year have taken about $2000 from me and every other Cantabrian to give to another island which we may never visit (I have no plans on visiting the North Island in the coming years). $2000 a year is more than I pay for electricity, so this is not an insignificant figure.

If the Canterbury and South Island fuel taxes and road user charges had been spent on Canterbury and the South Island, then I might receive some benefit. For example, my commute to work might be cheaper, faster, and more convenient. Also freight and business work, such as tradies going about their work, might travel more freely, meaning the costs of goods and services that I buy could be lower. This ‘highway robbery’ is one of the reasons I have such little respect for Wellington politicians – they legalise theft and then shrug their shoulders when challenged about it. At best I judge them to be unserious in what they do.

As much as I hate theft from me personally, there is a collective problem as well. The lack of transport investment in Greater Christchurch raises the issue of how sustainable population growth is for the city. If transport infrastructure spending doesn’t keep up with population growth, then that growth will at some point hit a wall. Christchurch will no longer be a success story. Congestion and slower roads will not stop growth this year or next but eventually it will. That is the lesson from Auckland, which under invested in its city building infrastructure in the post war decades causing its current infrastructure deficit, a housing crisis, and contributed to the productivity crisis. Repeating the same mistake in Christchurch would be folly.

Stay tuned for the fourth, and final, part of Brendon’s guest posts where he examines Christchurch’s mass transit future.

This post, like all our work, is brought to you by the Greater Auckland crew and made possible by generous donations from our readers and fans. If you’d like to support our work, you can join our circle of supporters here, or support us on Substack!

Processing...

Processing...

It’s not often mentioned but it is one of the things that Christchurch really has going for it is that the motorways never made it into the city centre.

Means there is still scope to have a CBD primarily served by rapid transit and cycling at some point in the future.

Good point Jezza. Foreign friends of mine when they visit Christchurch often comment on the potential of the city. It has good bones. But somehow this potential never gets realised. Which I attribute to the infrastructure institutional arrangements we have in NZ. I write about how we could improve this (not just for Christchurch but for all of our large towns and cities) in the final part of this series.

The motorway could have gone into the city by Hagley Park from Memorial Avenue, This was the early sixties. The opposition peaked when engineeting students took their survey tools etc into North Hagley making sure the radio station knew about it. And that was that.

I was a regular biker in Christchurch from the early 60’s when my parents brought me a bike which I used to bike down Main South Road and Riccarton Road to intermediate school. I don’t suppose they thought it was unsafe however I was knocked off my bike once but I think that was quite a bit later. There was certainly a lot less cars around. I was also a regular bus passenger and travelled on the electric train to Lyttleton from time to time. Battery railcars is an idea which could come again. I imagine that they were very low powered compared to what would be considered acceptable today. Still they could do the job.

Still I think the battery railcar only had a top speed of 30 mph. And thinking back about it the electric train to Lyttleton wasn’t much faster. Contrast it with the Southern line train with its 4 minute wait at Papakura. Although one day after it left late they ran it down the third main with passengers for Puhinui and Papatoetoe being told to get off at Middlemore and go back on the other line. However the trip between Otahuhu and Sylvia Park never seems to get above 30 mph. Don’t know why.

The 1920s electric battery train had a top speed of about 60kmh from memory, which is a little underpowered. It did though have very good acceleration, much better than steam or diesel trains.

It was also quiet, produced no coal smoke, no sparks (fire risk), and no diesel fumes.

So, we import ever single vehicle into our motu.

We subsidise motorists with state highways and other car dependency downstream realities.

We had fully electric trains capable of moving heavy loads more than one hundred years ago.

So we are not looking further enough into the past.

We need to go pre WW2 and WW1. With that vision, we might avoid the end times promised by the warmongering nations that surround us.

Peace and electric train travel, sounds like my idea of paradise on earth: but this century we live in apartments, NOT HOUSES!!!

bah humbug

Good insight Matiu.

I have thought to quantify the amount of car and oil imports we have in NZ as a result of our car dependency institutions.

I think it would be a considerable sum.

Frustrating no protection for a future rail corridor in the CBD was even mentioned post the earthquakes when the rebuild surely offered a blank canvass.

Yes that is a common criticism. A massive missed opportunity driven again by Wellington based politicians and institutions. Christchurch City Council and Mayor Bob Parker had a light rail proposal for the post earthquake redevelopment of Christchurch but the Rebuild Minister Gerry Brownlee did not even protect a corridor for transit in the city plan.

I have made a mistake with the regional funding figures. They are based on the three year period of 2024 to 2027. So Canterbury regional per capita transport underfunding is $2000 over three years not annually as I stated in the article.

This is still a significant amount and doesn’t affect the underlying point that if Canterbury receieved this funding it could afford a new MRT system.

Thanks, Brendon. Great roundup of the history and I’m really looking forward to part four.

Your welcome MrPlod

Yes thanks Brendon this is a really great and succinct summary of how we got to this suboptimal situation. You’ve really sharpened your knife – is not easy to get this story down so clearly, crisply and accurately. Bravo.

Just an observation as far as Christchurch is concerned…that the transition from trams to road vehicles was not as straightforward as it might seem although the case for road transport was becoming more of a fait accompli:

As reported by The New Zealand Herald on 28 December 1931, the comments of the General Manager of the Christchurch Tramway Board, Mr F. Thompson, did not auger well for the future of the country’s tramways:

“Wherever I have gone I have found tramway organisations in financial difficulties, said Mr F. Thompson, general manager of the Christchurch Tramways Board, who returned to New Zealand…after a tour of Great Britain, Canada and the United States.”

“All kinds of factors are operating against tramways, but the most serious, in my opinion, is the private motor-car…This is so equally in England and America. Car-owners not only prefer to use their own vehicles, but in a spirit of hospitality they take further patronage from the trams by filling their cars with friends. All I have seen confirms me in the belief that the Christchurch Tramways Board has done wisely in running trolley buses, as trackless trams are called, said Mr Thompson.”

“Mr Thompson said that trackless trolleys found favour especially in cases where the tram tracks had reached the stage when expensive renewals were called for. Although they did not possess quite the mobility of petrol buses, they were a very attractive proposition in a country like New Zealand, where petrol cost practically twice as much as in England.”

Not all lack of funding is bad. I’m certainly glad that Christchurch did not get expensive urban motorways. By not doing something that destructive, Christchurch has remained a more attractive city. Some spending can hurt more than it helps.