This is a guest post by Brendon Harre. It’s the second part of a post about Christchurch, it’s history, and what needs to change to fix it’s transport woes and and this part has been published on Brendon’s medium.

You can read part one here.

The water-era — From Pre-European times to 1867

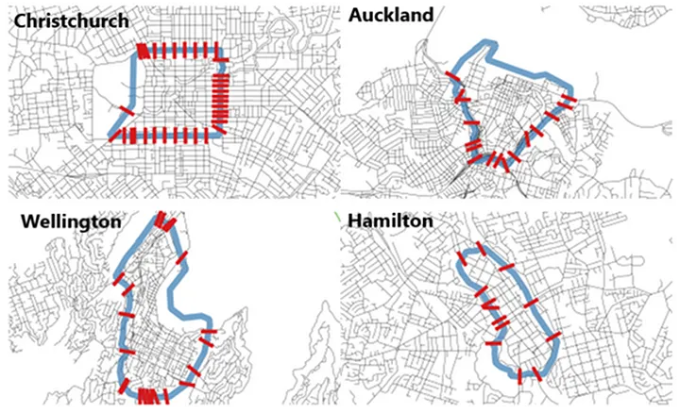

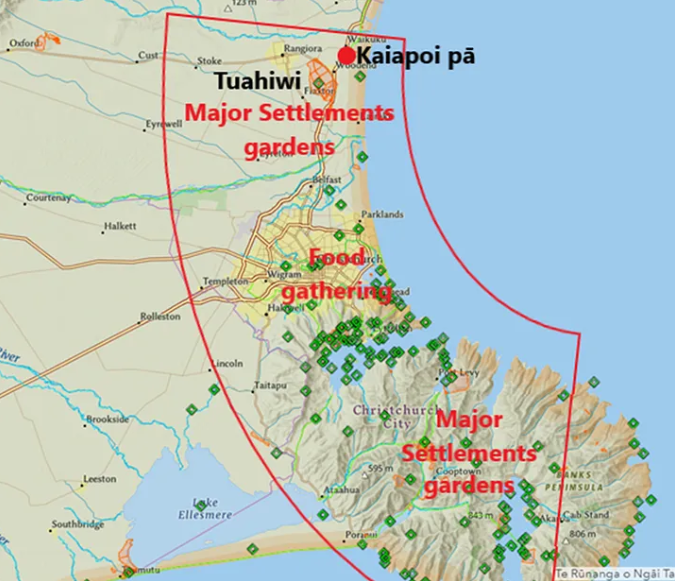

Ngāi Tahu’s cultural mapping project, Kā Huru Manu, shows the interplay between early habitation patterns and the natural environment.

Source: Ngāi Tahu Atlas

With its swamps, rivers and estuary, modern day Christchurch was back then an area primarily used for food gathering. The major Māori settlements were to the north and the south.

There are many lessons to be learned from the cultural mapping project. One intriguing story concerns the fall of Kaiapoi Pā in the early 1830s. After that happened, people shifted west to Tuahiwi. The name Tuahiwi means ‘the back ridge’, taking its name from the ridge that runs from Kaiapoi township to Rangiora.

Retreating inland to more solid land is what many Christchurch residents did after the earthquakes, too. Given the Ngāi Tahu shift to Tuahiwi, there may be merit in considering how the settlement can better fit into Greater Christchurch’s transport network.

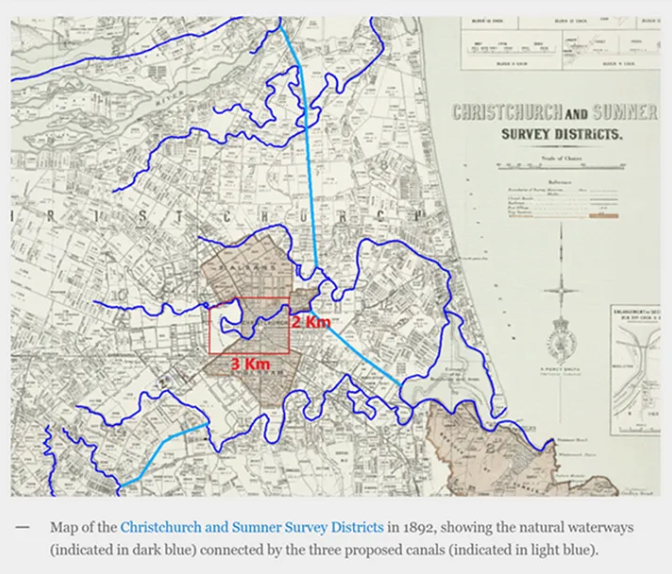

Christchurch city centre marked in red

Locating Christchurch on the Canterbury Plains instead of Lyttelton Harbour was the first major spatial milestone of the colonial era.

Captain Joseph Thomas, who oversaw the surveying of the new settlement, originally planned to connect the city and the port using water-based transport (this is well described in the article Canals through the Swamp). The plan involved coastal shipping from Lyttelton to the estuary and a canal linking the estuary to the city.

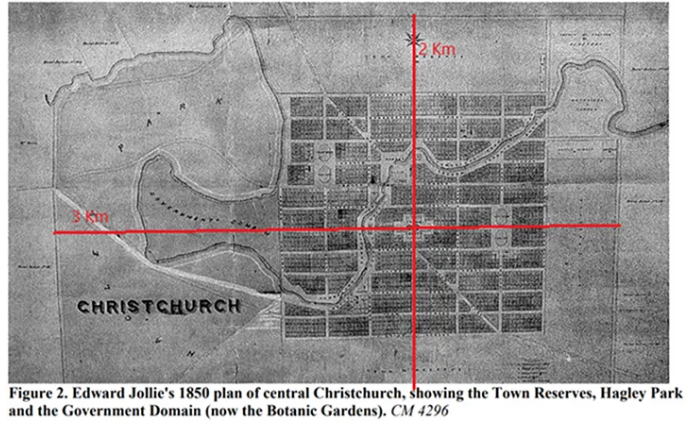

The 1850 city plan included a walkable city centre made of a grid of streets and a major green space (Hagley Park and the Botanic Gardens) on the western side. The total area was about 3km by 2km in size, measured from the surrounding boulevard streets (Bealey, Fitzgerald, Moorhouse, Deans and Harper Avenues). The town reserves on the northern, eastern and southern sides were set aside for future urban expansion.

The 1850 city plan included a walkable city centre made of a grid of streets and a major green space (Hagley Park and the Botanic Gardens) on the western side. The total area was about 3km by 2km in size, measured from the surrounding boulevard streets (Bealey, Fitzgerald, Moorhouse, Deans and Harper Avenues). The town reserves on the northern, eastern and southern sides were set aside for future urban expansion.

Being located on a plain, central Christchurch had 360-degree expansion potential. However, unlike Chicago the city did not set aside a wider network of arterial grid corridors, meaning it developed an ad hoc radial, or dendrite, arterial road system.

Linwood Ave cycle lane. The cycleway and green corridor 170 years ago was intended to be a canal

Linwood Ave cycle lane. The cycleway and green corridor 170 years ago was intended to be a canal

The proposed canals were never built. The space set aside for the city connecting canal is now a cycleway set in a green, boulevard road corridor.

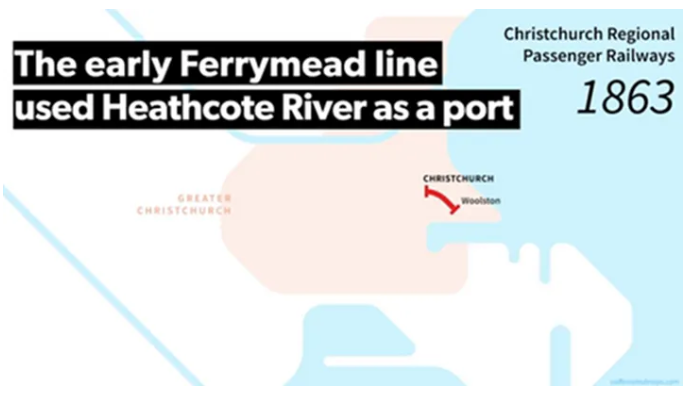

The only rail line of the water era was the connection from the estuary to the city.

The only rail line of the water era was the connection from the estuary to the city.

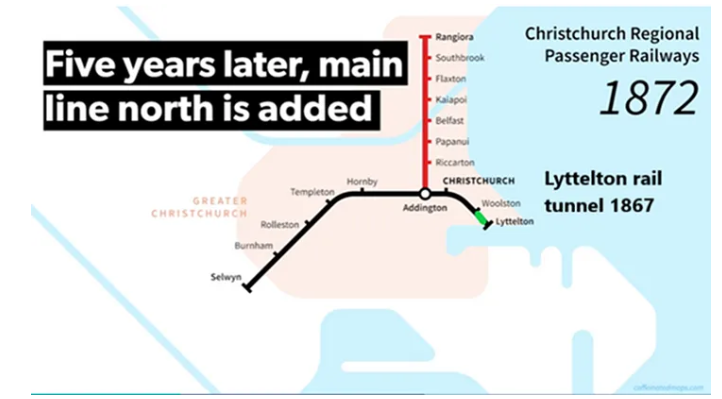

Passenger rail-era 1867 to 1934

In 1857, the Canterbury province decided to construct the 2.6 km Lyttelton rail tunnel, a major evolution of the region’s spatial plan. The Superintendent election that year had the rail tunnel as its focus, with the pro-rail candidate William Moorhouse winning the election. The tunnel was opened in 1867 and cost £200,000, which was financed by a provincial government loan. Canterbury had only 12,000 people in 1857, so land sales emerged as the best revenue source to repay the debt.

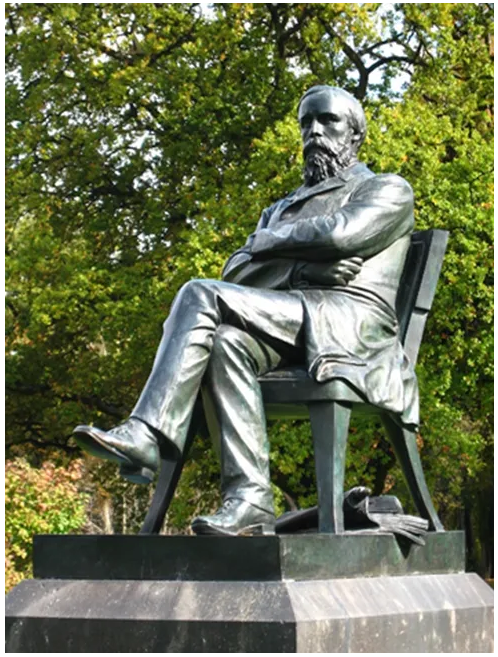

Canterbury provincial government Superintendent statue. The inscription on the stone plinth reads: William Sefton Moorhouse to whose energy and perseverance Canterbury owes the tunnel between port and plains.

Canterbury provincial government Superintendent statue. The inscription on the stone plinth reads: William Sefton Moorhouse to whose energy and perseverance Canterbury owes the tunnel between port and plains.

This was a practical application of Wakefield’s sufficient land price theory: the concept that adding infrastructure and amenity to land can raise its commercial value above a sufficient selling price. Land sales can then repay the incurred costs. In essence, this is a land value capture mechanism.

In effect, Canterbury had created an infrastructure provision model involving democratic governance, evolution of a spatial plan and an infrastructure-funding mechanism.

It’s likely that Canterbury’s success with rail in the 1860s was a leading factor contributing to Vogelism in the 1870s (massive expansion of the railways as a nation-building exercise).

Premier Julias Vogel’s greater centralisation of transport provision had undoubted benefits, including standardisation of the rail gauge. However, the scheme wasn’t as successful as it could have been.

Vogel wanted over 2 million hectares of ‘waste’ land around his proposed rail corridors as a Crown endowment. This would have allowed the Crown to own land close to the newly constructed rail corridors which it could then sell at high prices to fund the infrastructure costs. In 1873, Parliament voted against the measure. Vogel’s scheme couldn’t capture the value it created, meaning infrastructure expenditure had to be financed by central government debt repaid from general taxation.

As it eventuated, Vogelism created a disconnect between infrastructure provision and local land use effects, because the local households, farms, firms and workers didn’t contribute towards the direct benefits they received (higher incomes, higher land values, lower transport costs, etc). The wider New Zealand public purse essentially subsidised large increases in private gain. This is part of a long-term pattern of New Zealand being addicted to land speculation which is a fundamental weakness to its economy and society.

The disconnect between central government infrastructure provision and its land use effects may seem like an obscure historic fact, but it’s an issue the government has yet to resolve more than 150 years later.

The cost-benefit tools that government transport agencies use to prioritise new transport projects do not consider land use effects despite repeated recommendations by experts that they should.

What transport projects New Zealand selects is largely a political choice. More formal tools like funding being based on revenue obtained from tolls, congestion charges, car parking fees, capturing rising land values, or capturing some of productivity income gain have been ignored. Transport spending has been politicised meaning techniques to provide a more consistent pipeline of work and to contain costs have been ignored. Also, sensible mechanisms to constrain infrastructure cost escalation, such as spatial planning and acquiring land corridors for right of ways before land prices increase have been ignored. In many areas New Zealand has significantly higher build costs than other developed countries — the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission identified cost premiums for four types of complex, large-scale projects: urban and rural motorways, road tunnels, and underground rail projects.

As Colonial Treasurer (1870 to 73) and as Premier (1873 to 76), Vogel championed the building of over 2000 km of rail by 1880. It was financed by public debt, which doubled from £7.8 million in 1870, to £18.6 million in 1876. Repaying the debt in the following decades probably exacerbated the 1880s Long Depression. Given New Zealand’s current government spending deficit, and the increasing burden of funding higher superannuation and higher elderly healthcare costs it doesn’t seem wise or even doable for New Zealand to address its infrastructure deficit from central government debt that needs to be repaid by the general taxpayer. New Zealand risks being trapped in another long depression where it cannot afford productivity sustaining infrastructure because of tight fiscal budgets due to increase expenditure on the elderly.

Back in the 19th century Canterbury did get infrastructure upgrades, the wider rail network quickly followed on from the decision to build the Lyttelton tunnel. The southern line was established before the tunnel was opened in 1867; the northern line was added five years later by 1872.

The provincial government system was abolished in 1876. By that time the Canterbury province was in good financial health as land sales had repaid the tunnel debt.

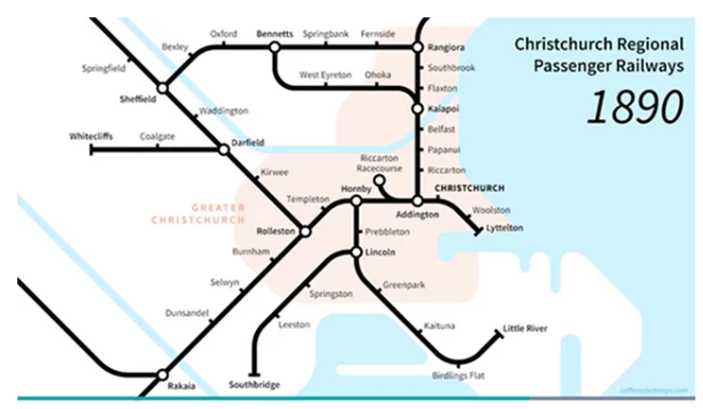

Despite the political restructure, the rail network continued to expand.

However, the railways included some major spatial planning flaws which were never remedied. The off-centre location of the central train station has long been considered suboptimal. In 1868, The Press newspaper wrote a whole editorial on the topic, stating “Christchurch station would never be accepted as Christchurch except on a railway ticket”. There have been various spurs and loops suggested since 1868 to correct the off-centre problem, but never to the point where the necessary corridor protection and funding mechanisms were established.

Rail-era — Bicycles are added from 1880

By its very nature, rail complements other transport modes. From the beginning, walking to the railway station was the norm.

In Canterbury, bicycles were quickly adopted into the local transport system.

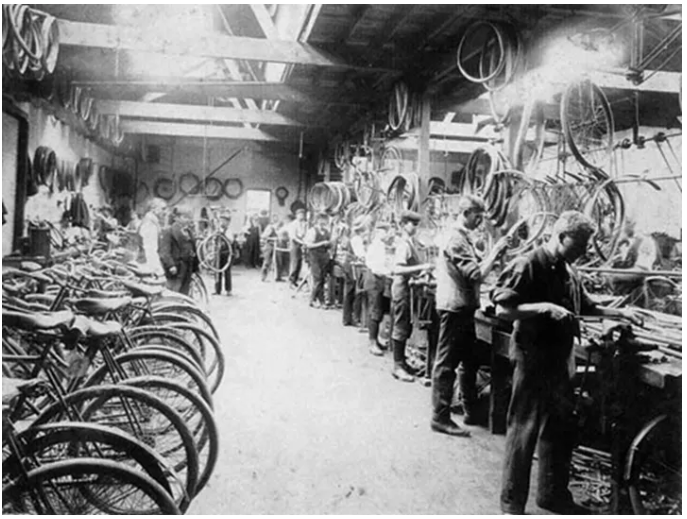

Nicholas Oates and Alexander Lowry began the Zealandia Cycle Works in Christchurch in 1880. It was the largest bicycle factory in New Zealand or Australia in the late 1890s — turning out branded safety cycles as can be seen in the above picture. Source

Nicholas Oates and Alexander Lowry began the Zealandia Cycle Works in Christchurch in 1880. It was the largest bicycle factory in New Zealand or Australia in the late 1890s — turning out branded safety cycles as can be seen in the above picture. Source

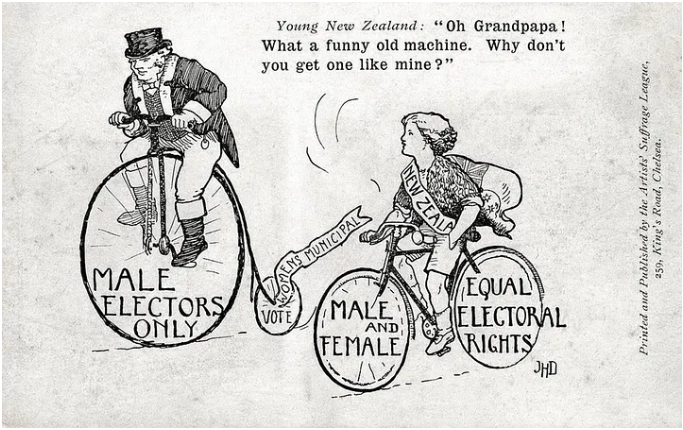

Even before the Christchurch earthquakes, the city had fewer high-rise buildings than Auckland or Wellington. This doesn’t mean the city lacked agglomeration opportunities. Christchurch’s history of cycling and women’s suffrage is an example of the agglomeration benefits the city achieved in the past — a critical mass of networked people was able to share new ideas.

Women in Christchurch were quick to use bicycles in the 1890s to advance the suffragette movement. In 1892, The Canterbury Times reported there were 4000 cyclists in Christchurch out of a population of 51,000. According to the paper:

everyone cycles — both sexes, all ages, all ranks. Ladies make calls thirty miles out…. There were lady cyclists in Christchurch when they were practically unknown in other parts of the world, and they cycled in knickerbockers, and tasted the freedom of the reform dress when their sisters elsewhere were merely talking of it in whispers.

The suffragette campaign to get women the vote was led by Kate Sheppard and her Christchurch supporters. The major success of this campaign was organising a quarter of the nation’s women to sign a petition demanding the right to vote. In 1893, New Zealand became the first self-governing country to grant all women the right — to vote in the nation’s parliamentary elections. After Otago/Southland, Canterbury had the highest number of signatures.

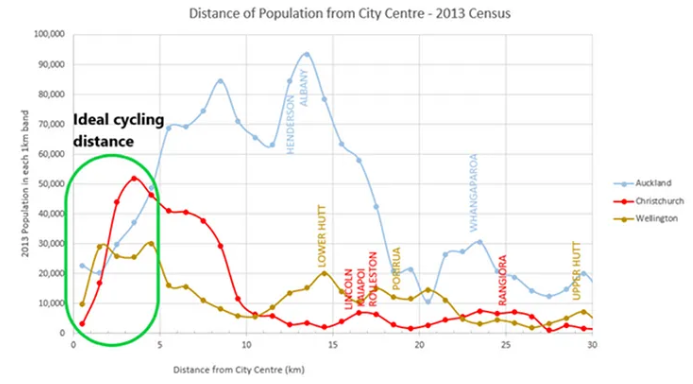

Source — Different Cities, Different Shapes 2/2 article in Talking Transport Christchurch

Source — Different Cities, Different Shapes 2/2 article in Talking Transport Christchurch

Christchurch’s city centre has the most access points of any comparable city in New Zealand. Due to the city expanding in all directions, a larger number of people can live within 3–4 km of the city-centre and still have easy access to the amenities it provides. Combined with Christchurch’s flat terrain, this makes the city ideal for cycling. In the past, Wellington and Auckland didn’t have as many people living within such a convenient cycling distance, although Auckland’s city centre growth since 2013 means it has overtaken Christchurch.

Rail-era — Trams are added from 1880

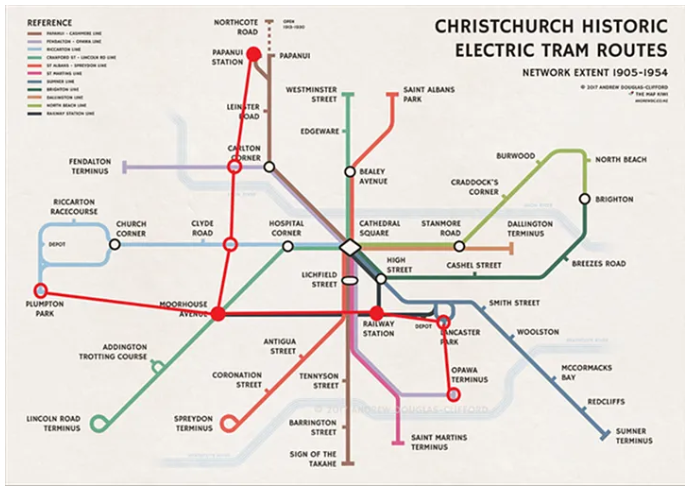

Trams in the past integrated with the railway network at Papanui, Addington, and Christchurch railway stations (red dots)– there were more locations (red circles) where integrated services could have been established to create a more ‘gridded’ network

Right from the start, Christchurch’s trams shared road space and intersections with other road users. When buses replaced trams in the 1930s through to the 1950s, routes largely remained the same.

Passenger trains were different: they didn’t share the rail corridor with other modes, and they had the priority where tracks crossed roads. Trains could therefore travel at higher speeds and their travel times were more reliable as they weren’t affected by road congestion.

Passenger trains were different: they didn’t share the rail corridor with other modes, and they had the priority where tracks crossed roads. Trains could therefore travel at higher speeds and their travel times were more reliable as they weren’t affected by road congestion.

Christchurch’s trams and trains were an integrated public transport service — one fed the other. Trams provided a solution to the city’s off-centre rail station problem. In 1880, Christchurch’s first steam tram provided a service from Cathedral Square to the Christchurch railway station on Moorhouse Ave via Colombo Street; shortly after, another service was added via High St.

Tram services were initially run by private companies, but electrification required more capital so, from 1905, they were built by municipalities. Local government funded the electrification and the expansion of tramlines by taxing property in the form of rates on land and capital value (another land value capture mechanism).

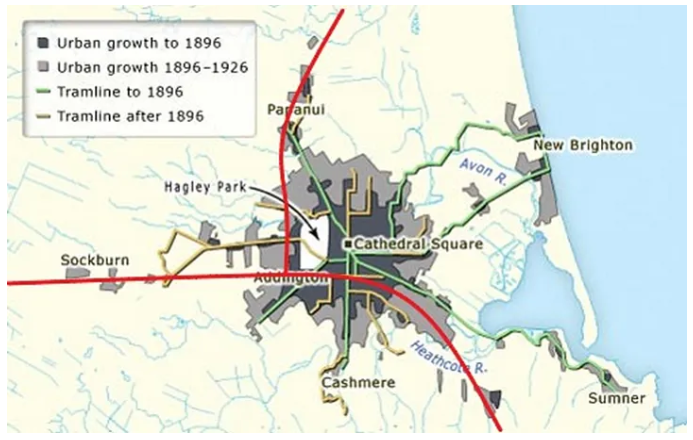

Approximate route of passenger rail in red. Source

Approximate route of passenger rail in red. Source

Up until 1926, urban growth in Christchurch largely followed the train and tram lines. It was a successful period for the city. Its local government could afford to fund the infrastructure needed for growth and rents were affordable for residents (renting in Wellington cost 45% more at the time).

Stay tuned for the next part of Brendon’s guest posts.

This post, like all our work, is brought to you by the Greater Auckland crew and made possible by generous donations from our readers and fans. If you’d like to support our work, you can join our circle of supporters here, or support us on Substack!

Processing...

Processing...

I suggest correcting the spelling of Kate Sheppard’s surname – it wasn’t Shepherd.

Oops! Good spot, fixed

Apologies. Fixed on my site, too.

On this topic note that women who campaigned in NZ for the right to vote are known as Suffragists not Suffragettes which was adopted later on in the UK. Kate Sheppard would have called herself a Suffragist (from Prohibitionist) .

Thanks Brendon for the interesting Christchurch history!

Your welcome Pippa. I am proud of what Kate Sheppard did and that she is from Christchurch even though I misspelled her name and what she called herself.

I noticed you mentioned “ in many areas New Zealand has significantly higher build costs than other developed countries…”. Many detractors to your arguments will claim that it is just an unavoidable cost due to New Zealand being too far removed from the rest of the world, and “it is what it is. There are no realistic counterfactuals scenarios that we could reasonably create”.

How would you respond to such claims?

I think this issue is an article in its own right. Unfortunately, atm I haven’t the time or energy to dedicate to it.

When I have looked into it, not all countries have experienced infrastructure cost inflation like NZ has for many decades now.

The correlation doesn’t seem to relate to country size or isolation. The correlation is the English-speaking places are worse. Not exactly sure why. It seems to relate to the planning/ design phase of construction.

Speculation is that it is related to common-law history or that opposition to infrastructure from individuals and pressure groups is more enabled.

Maybe the English-speaking world went further down the privatisation/lack of in-house infrastructure building expertise.

I have looked at Italy which hasn’t experienced infrastructure inflation and in large part that seems to be related to efforts to control corruption/mafia so their procurement systems are much more transparent and professional.

I don’t think NZ holds itself to high standards. Our infrastructure funding models are essentially broken/politically corrupt. Yet they are not reformed.

How can the National Land Transport fund be planning to spend $30bn primarily on the state highway network in the coming decade more than it receives in road user charges?

In a constrained fiscal environment where the finance minister every year has to find in their Budget either extra revenue or savings to the tune of one $billion for additional superannuation payments this cannot continue. At some point something will break, and reform will be inevitable.

I agree, institutional factors and culture seem to have something to do with it. The problem is it is difficult to quantify them.

I’ll recommend a book, The Con by Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington the Infantilisation of government and the public sector is very real. In the English-speaking world, very few attempts are made to turn the tide and the few attempts either get given up on because it also costs money to bring and build up in house capacity usually after change of minister or government

Good comment dpalenski.

Proper infrastructure delivery reform is a serious long-term commitment. I see little evidence NZ’s political system is doing the hard work to understand the dynamics of what would make reform work from either left-wing parties (they are lazy and put their heads in the sand) or the right-wing parties with their superficial claims blaming infrastructure deficit issues on overspending local governments.

I think Christchurch would really benefit from reinstating some of these tram routes as a light rail network. Papanui Rd and Riccarton Rd especially have existing bypasses in Cranford St and Blenheim Rd, although no doubt there would be resistance much like Dominion Rd.

From there commuter rail could be introduced to allow trains from Rangiora, Rolleston and Ashburton to connect to this network.

I agree Jezza. That is what I am trying to explain would be best for Greater Christchurch. I agree with the current MRT proposal of light rail on Riccarton and Papanui roads except at stage one instead of light rail ending at Church Corner it should go to the University.

Light rail should be used to access significant locations needing high-capacity transport corridors, such as the University, the main hospital (more people work there than anywhere else in Canterbury) and the city centre that are away from the main rail corridors.

There should be transit connecting stations in Riccarton and Papanui to transfer between the Rolleston and Rangiora rail corridor and the Riccarton and Papanui light rail line.

I don’t think the stage two of the current MRT proposal to extend light rail to Hornby and Belfast is sensible because they are both on the rail corridor.

I don’t think MRT in Greater Christchurch should be a choice between street running light rail versus passenger trains on the main rail corridors. They should both be used to create a more complete MRT network.

Agree, I think Bob Parker was on the money with his proposal that would take in the University and the Airport, although the Airport would have to be another stage.

I’d extend LR to New Brighton and Cashmere before extending to Belfast and Hornby.

Agree. It was such a shame light rail wasn’t included in the rebuild plans. Parker was right and Brownlee was wrong.

Light rail from the Uni to Riccarton Road to the city centre and out to Papanui and passenger rail from Rolleston and Rangiora would both be relatively straight forward projects compared to what Wellington and Auckland have done in the past with their train networks (Tawa Flat Deviation, and the CRL). It is also much simpler than their light rail proposals.

After they are built Christchurch can reassess what is the next best step. It will have several options which is probably a good thing.

I spent 4 nights in the Observatory Hotel last week in the Arts Precinct, and was pleasantly amazed and astonished as a recovering Aucklander at how high the cycle lane use was in rush-hour and on the weekends, how efficient the electric buses were, and how walkable the entire town centre was. Also it’s clear the walkable blocks are expanding out beyond the new stadium.

Shoutout to everyone who restored the entire university block including the Observatory and Physics blocks to turn into the boutique hotel.

We only used the car to go out to The Tannery retail centre.

I hadn’t been to the centre of Christchurch for a few years and it was a total revelation.

I am glad you had a good visit AD. I think Christchurch is gradually putting the earthquakes behind it and the city is moving into a new phase of its history.

I was born just too late to witness Trams in Christchurch but was brought up to cycle and was a regular user of the number 8 bus which ran down main south road past our home. Blenhiem road was the old stock route and ran along the railway line. I can remember the f class steam shunters working at the Christchurch Station. The settlers got a lot of things right.

Anything to do with rails for Christchurch will be costly and to delay/ not proceed the building will likely result in even greater costs in the future. Probably rearrange what KiwiRail names Middleton rail yard. Redevelop the siding area (with close to 30 strips of track). Build a new siding for coal wagons out by Rolleston somewhere. The Middleton siding might have 3+ hectares to be repurposed as a central rail station and minor bus hub. Probably have to build a temporary container siding out by Sefton somewhere while the MNL is upgraded, to allow north/ south container traffic via rail to continue. Kilmarnock street station could be a hub to bus west to Ilam or East to the central city. (Buses get priority traffic lights etc)Middleton station/ hub could require some expensive overbridges. Trains- probably hybrid/ (non-lithium) battery so only point charging overheads are used. Main aim would be to have a public transport option that is functional and reliable.

Interesting article thanks Brendon.

Your welcome Grant