This is a guest post by Shaun Baker. It originally appeared on his blog Multimodal Adventures and is shared here by kind permission.

A necessary component of creating an inclusive and equitable city is accessibility. Designing our cities with accessibility in mind is important so everyone, particularly our disabled communities, can access and thrive in our built environments without experiencing any barriers.

While significant progress has been made to improve our places in our cities to meet the needs of those with physical, hearing and visual disabilities, it’s also important to make changes in the way we design our cities to accommodate those with invisible disabilities as well, which includes neurodiversity.

For those who aren’t familiar with the terms neurodiversity, or neurodivergent, they refer to those living with neurological and developmental conditions such as ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and dyspraxia.

Neurodivergent people’s brains function differently from those who are neurotypical, which affects the way they learn, process and behave. As a result, they can experience difficulties when interacting with our built environment, especially places that are not designed around the needs of neurodivergent people. This is something that I have experienced when navigating around our cities as someone who is autistic.

Neurodivergent people can be sensitive to various elements of our environments (eg: noise, lighting, smell, and touch) and can get overwhelmed and experience sensory overload, increasing the stress and anxiety of a neurodivergent person. These sensitivities to our environment can vary from one individual to another. For example, one person can be hypersensitive to noise and get overwhelmed, while another is hypersensitive and underwhelmed.

In this post, I discuss how we can design our spaces in our cities to make them more accessible to our neurodivergent community.

Creating a low sensory experience when visiting shops and facilities

I want to start by discussing how to create a more accessible environment to access stores, shopping centres and other major amenities. This is important, as the sounds, lighting, and smells within our stores, supermarkets and shopping centres can trigger sensory overload. A survey completed by the National Autistic Society in the United Kingdom found that 64% of autistic individuals have avoided visiting stores as they have found the experience too distressing.

To help make the retail experience more accessible to neurodivergent people, some stores, supermarkets and shopping centres have introduced “quiet hours” – times when, for an hour in the week or a day, the lighting in the store is dimmed and the volume of music and other sounds is reduced.

In the United Kingdom, before being cancelled in 2020 due to Covid-19, the National Autistic Society ran an annual Autism Hour campaign to improve the public’s understanding of autism. This campaign was successful in raising awarenessl, with a 220% increase in businesses participating in the campaign by implementing a quiet hour in 2018.

Quiet hours have been introduced in Aotearoa, including at other facilities, such as gyms, museums and observatories, and stadiums – with Eden Park in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland having a sensory room available during events to a create a calming environment and to reduce sensory overload.

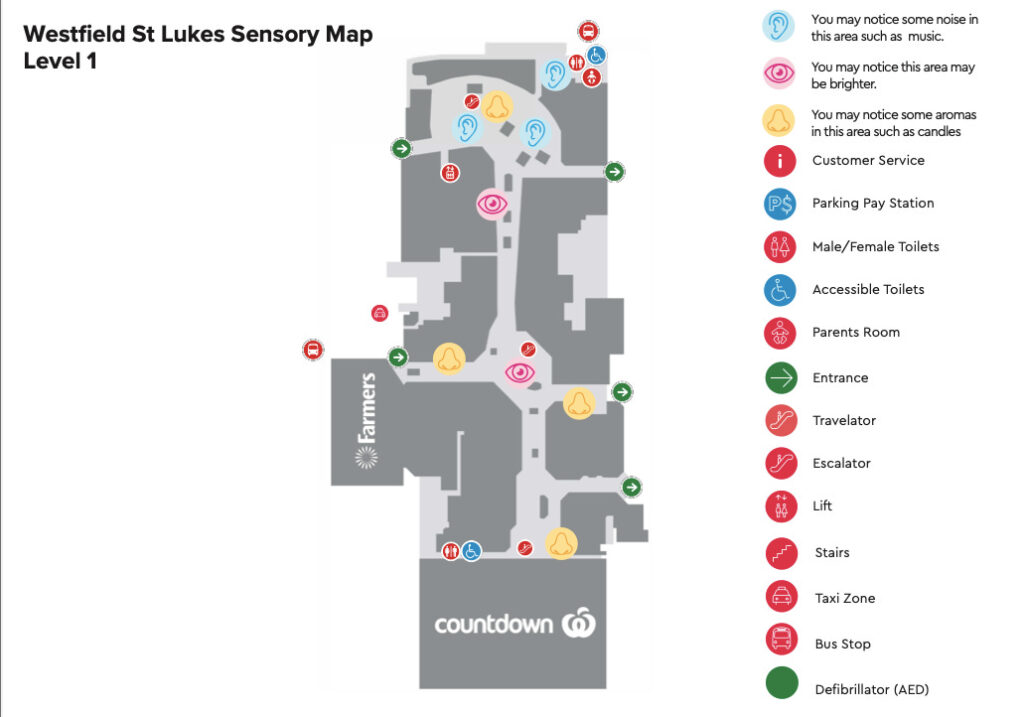

Westfield, at their St Lukes shopping centre in Tāmaki Makaurau, has made a sensory map available to assist neurodivergent people and their relatives in creating a more comfortable experience when visiting the mall.

Scentre Group (which owns and operates Westfield shopping centres in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand) is also a member of the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower scheme, which distributes sunflower lanyards to those with invisible disabilities to discreetly let staff know that they may require assistance. As part of their involvement in the scheme, Scentre Group have been delivering training to their staff, service providers and retail partners on how to support customers with an invisible disability.

Making public transport more accessible

Using public transport can be stressful for neurodivergent people as the sounds of chatter and loud music on the radio or from other passengers’ speakers can be overwhelming, and can discourage neurodivergent people from using public transport.

This is something that I experience, and I wear noise-cancelling headphones during my trips on public transport to help mitigate this.

Ways to actively create a low sensory environment on our public transport networks include:

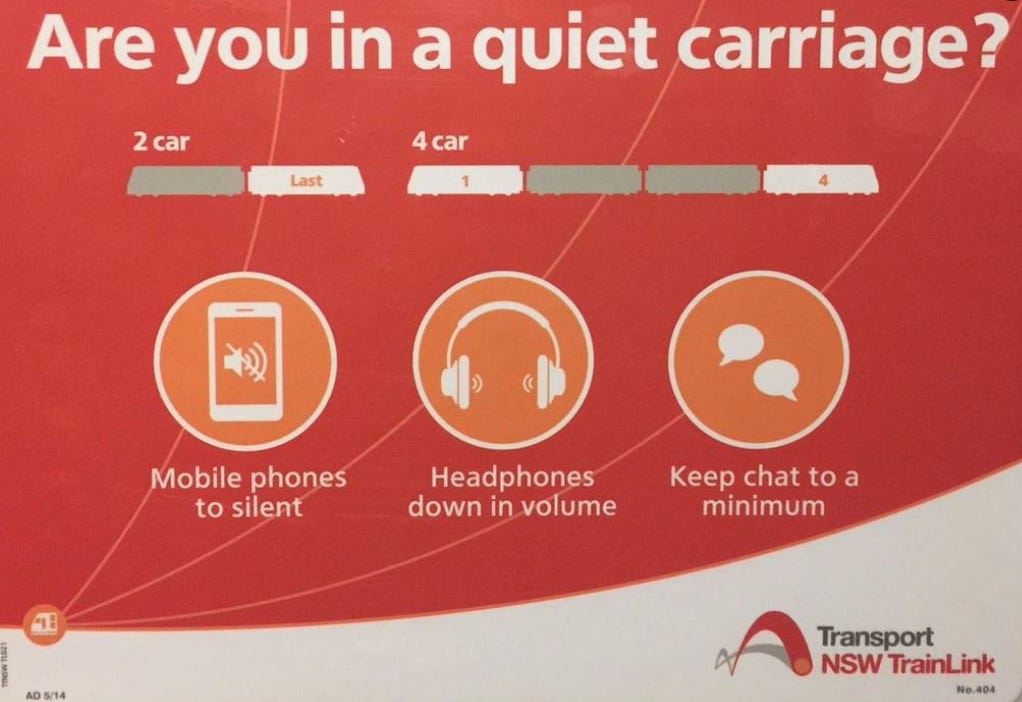

- Introducing quiet carriages on commuter rail services, which are common in the United Kingdom and Australia.

- Reducing the volume or turning off sounds on trains and buses except for audio announcements for blind and low-vision passengers and for emergencies.

- Dimming the lighting on buses and train carriages to reduce sensitivities to fluorescent and artificial lights – to which half of autistic people have experienced severe sensitivity.

- Having quiet waiting areas at public transport stations and interchanges.

Crowded spaces can be difficult for neurodivergent people to navigate. I have found getting around in crowded interchanges and on overcrowded buses and trains overwhelming, as I fear getting lost and find them too noisy.

Because of this, I avoid using public transport at certain times. Increasing the frequency of services, having larger vehicles (eg: double-decker buses), and upgrading at-capacity corridors to rapid transit (either bus rapid transit or light rail) will help avoid overcrowding on our network, and make public transport a more comfortable experience.

The final point is that training needs to be available to staff in our transport authorities on how they can assist in creating easier journeys for neurodivergent people when travelling via public transport.

In Sydney, about 90% of Sydney Trains and NSW Trainlink customer service staff have undertaken training on how to assist people with invisible disabilities. This training has been successful in increasing awareness of invisible disabilities on the city’s train network. Transport for New South Wales has also been providing sunflower lanyards through its partnership with the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower scheme, to help support the estimated 138,000 passengers with an invisible disability who use the states rail network every day.

Last year, Auckland Transport released a series of videos called Full Access, to educate ferry operators on how to assist disabled people when accessing ferries to get around Tāmaki Makaurau. This included a video made in conjunction with the Halberg Foundation, one of the disability organisations that sits on AT’s accessibility advisory groups, to help educate operators on how to support neurodivergent individuals when they are using the ferry network.

Shaping more inclusive urban environments

Despite an increased understanding of neurodiversity in recent years, the needs of neurodivergent people have generally not been considered in the design of our places. Designing our neighbourhoods around the sensory needs of neurodivergent people is important to make it easy to connect and navigate around our city.

According to the “The Six Feelings Framework” developed by the Knowlton School of Architecture at Ohio State University in the United States, in order for public spaces and infrastructure to be inclusive to autistic people, they need to feel:

- Connected: Because they are easily reached, entered and or led to a destination.

- Free: Because they offer to create autonomy and independence.

- Clear: So they make sense and do not confuse.

- Private: To create boundaries and sanctuaries.

- Safe: To reduce the risk of injuries.

- Calm: Because they mitigate many physical and sensory issues associated with autism.

What designs can help achieve this? The paper “Shaping Places for children with autism spectrum disorder” by Gemma Dioni and Paula Bradbury includes tables with suggestions for making our urban environments more inclusive to neurodivergent adults and children. These suggestions are based on the findings from their research, which included interviews with relatives of autistic individuals and advice from landscape architects in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Some of these suggestions include:

- Designing wider footpaths and shared paths to reduce anxiety, as crowded footpaths and fluid streetscapes can be stressful as they give no sense of boundary. They can also be difficult to navigate, particularly for those who have difficulty judging distances, space and the speed of cyclists and scooters etc.

- Having more pocket parks, and incorporating biophilic design into building developments and public spaces, as connecting with nature can help create calm and relaxing environments.

- Use soft or smooth materials, and muted or neutral colours, as it can help create a more calming environment. Avoid using materials, patterns and colours (such as reflective materials and vivid tones) as they can cause discomfort, glare and visual overload.

Playgrounds are an important public space to help neurodivergent children develop their self-esteem, social skills and communication skills. Our playgrounds can be made more inclusive by:

- Grouping noisy and quiet activities to help encourage social interaction.

- Offering a wide range of sensory experiences through the use of auditory, tactile and visual play equipment.

- Having play equipment at different heights and widths to improve their fine motor skills.

- Installing visual communication boards at playgrounds and picnic areas to assist children who are non-verbal in communicating.

Incorporating “The Six Feelings Framework” and adopting some of the suggestions discussed above into the master planning of developments, and the design of our public spaces and infrastructure, will help create more inclusive environments for neurodivergent adults and children.

If the barriers that have a serious impact on the quality of life for our disabled communities remain, we will not be able to achieve an inclusive and equitable city.

The goal is to eliminate the barriers that our neurodivergent communities experience when navigating around our urban places, getting from A to B via our public transport networks, and when visiting major amenities and facilities in our neighbourhoods. This will help shape a more welcoming built environment for neurodivergent adults and kids to enjoy and thrive.

Removing these barriers doesn’t just benefit neurodivergent people, it benefits neurotypical people as well, leading to more inclusive and equitable towns and cities for all of us.

Further reading and listening:

- Shaping Places for children with autism spectrum disorder – by Gemma Dioni and Paula Bradbury.

- The Invisble City: Public Transport through Neurodivergent Lenses – by Lucinda Miller.

- Autism: Why Playgrounds Matter? – by play equipment supplier Playworld.

- Urban Planning and Neurodiversity – Better Planners Podcast.

Processing...

Processing...

I feel like the times given for quiet hours are too short and inconvenient. If you’re working full time Westfield’s quiet hour of 10:30am to 11:30am on a Tuesday probably isn’t an accessible time slot. I don’t really see a reason why quiet hours can’t be extended to a quiet day for that matter, surely the changes in atmosphere aren’t disruptive enough to most shoppers that they can’t go to St Lukes on Quiet Tuesdays

Very nice post, thanks. There’s a lot we could need to do better. The Dioni and Bradbury suggestions you’ve listed would simply make nicer places for us all. As you say, “Removing these barriers doesn’t just benefit neurodivergent people, it benefits neurotypical people as well, leading to more inclusive and equitable towns and cities for all of us.”

Good on AT for those videos. Is there one for the Travelwise team to consider? (Is there still a Travelwise team?)

Auckland is far too noisy on the whole. The traffic is bad enough – and we know that the health effects of this noise include raising blood pressure, which of course is a killer. The piped music at malls can make shopping hideous, especially with kids. But worst of all seems to be the noise level at “events”. Children’s events are often the worst, which is particularly crazy. And I tend to avoid events with a competitive sport element because there’s usually someone with a microphone ruining the whole place.

The audio on trains and buses should be an easy one to address. Much as I enjoy taking Te Huia, the volume and length of the announcements is a bit much. We could have a silent carriage that only presents information via a screen or message board.

Not fair on vision impaired people who might like to also have a quieter carriage just with announcements only. It’s quite simple shorten the announcements to “Next stop Huntly” similar to how “Quiet carriages” are done on the OSCARS in Sydney. We don’t need all the extra talking and Te Reo lessons if you want to hear these announcements sit in a normal carriage that seems like quite an easy fix.

Yes that would work too. Anything better than what feels like 2 minutes at full volume. It’s not like the stops ever change…

Good post by Shaun, I don’t know much about this area. I enjoy his pics of new developments etc from around the city centre on ‘X’ too.

Thanks very much, Shaun, for your invaluable article. Generally, the needs of neurodivergent people are not readily understood and hence not provided for in the built environment. Really appreciate the useful references and have forwarded this article to others in my network.

Thanks for this Shaun. As someone with ADHD, frequency of bus and train services are key because I am typically running late and find timetables stressful. I loved being in Tokyo or London, where you could just show up and know a train wouldn’t be very far away without having to clock watch / beware of your time.

I do appreciate the modern terminology around these “disorders”. However, they are not actually a problem. We, the weirdos, eventually find out that we are superior to the squares, and after that, actually embrace our differences from the normals.

It is great that we are encouraging our younger generation to embrace themselves earlier, instead of trying to repress, oppress, or ignore the colourful patchwork that we are as humans.

But if this is the way to fund this stuff, then let us use every piece of vocabulary we have to ensure that history’s mistakes are not repeated!

bah humbug

Great post!

I have a physical disability (hidden), along with ADHD, Autism and Dyslexia, and I have struggles with public transport and driving.

With driving I find the visual “noise” very challenging – because of this I only drive when public transport can’t work for me.

I’m on a very busy bus route with double decker buses, and even though I have joint issues I clamber up the stairs as it is too noisy and crowded downstairs and a lot of the seats (if available) are uncomfortable. I just wish the bus drivers would wait for me to be seated before they take off. The announcements are far too many and too long. I wish they were very short and to the point which would make it easier for my brain to focus on. I think there are situations where having te reo is great, but on a bus with regular stops it creates far too much “noise” – there are far more people with disabilities than there are te reo speakers. Trains could also be better – I get frustrated in Newmarket in particular with last minute platform changes, my brain struggles to get my slow body moving in time to get to the next platform. I wish other passengers would be more thoughtful of others around them and not talk too loud or play music too loud on their devices meaning others around can clearly hear it (not good for their hearing either).

Re shopping, I start out enthusiastic, but usually give up quickly due to the crowds and noise.

Thanks Shaun,

Learnt a lot from your post and will check out the resources you mention.