This is a guest post by Darren Davis. It originally appeared here.

Perth, population 2.1 million, sits on the Indian Ocean and is the capital city of the mineral-rich state of Western Australia which is literally bigger than Texas. Three times bigger in fact. And like Texan cities, Perth sprawls. Seriously sprawls. It stretches more than 120 kilometres from north to south. There is a major and still developing motorway network focused on the Mitchell Freeway to the north and the Kwinana Freeway to the south. It all sounds like a perfect recipe for a public transport disaster area. Yet it has arguably Australia’s best overall public transport network structure. And unlike most cities, public transport patronage is pretty much back to pre-pandemic levels. So what is the secret to Perth’s success and how did it get there?

The bad old days

While Perth is now regarded as somewhat of a public transport role model, it wasn’t always that way. As was typical of the 1960s and 1970s, public transport patronage was declining due to uncompetitive travel times with competing motorways and suffered from significant underinvestment. This culminated in 1979 with the closure and bus replacement of the Fremantle Railway Line. This triggered one of the biggest public protests in Western Australian history. Ironically the protests about this closure set up the social licence for the revival of public transport in Perth.

The start of the rail revival

A new state election in 1983 saw Labor elected on a promise to re-open the Fremantle line which duly happened in July of that year. Patronage quickly returned to pre-closure levels. But the infrastructure, particularly the rolling stock, was in such bad shape that a decision was quickly taken to electrify the Perth rail network, which took place between 1986 and 1991, accompanied by new Electric Multiple Units.

In another ironic twist, Perth’s run-down diesel rolling stock, post-electrification, was flogged off to Auckland at bargain basement prices, saving Auckland’s rail network from the then-threatened imminent closure. But that is a story for another blog post.

The electrification covered the then 64.8 kilometre three-line legacy rail network, made up of the Fremantle, Armadale and Midland lines. But these lines were largely oriented east to west, whereas the bulk of the city’s growth was to the north and south, with growth set off by the construction and extension of the Mitchell and Kwinana freeways.

Northern Suburbs Transit System

The rapid and sustained growth of the northern suburbs of Perth during the 1970s and 1980s placed a considerable strain on the existing bus system and the Mitchell Freeway. The solution decided upon was the new Joondalup Rail Line, largely in the median of the Mitchell Freeway, tightly integrated with a bus network built around a large feeder bus network at stations. The line opened to Currambine, one station north of Joondalup, in 1993 and was extended as far as Clarkson in 2004, and further extended to Butler in 2014. And it is now being extended 14.5 kilometres even further north to Yanchep, with two intermediate stations, adding 150,000 people to the rail catchment.

Conventionally, having a railway in a motorway is not considered best practice, but several key features of the newer parts of the Perth rail network mitigate against this.

- Wide station spacing enables sustained 130km/h running in the freeway median on narrow gauge tracks while traffic is at a near-standstill in the peak. Like Auckland’s Northern Busway, this is visible self-marketing for public transport.

- Even in uncongested conditions, rail travel is time competitive with car travel and much faster in congested conditions or if there is an incident on the freeway.

- Both train and key feeder bus services are frequent all-day, every day of the week.

- Excellent integration with a bus feeder network at bus interchanges, fully integrated into the station, enables seamless fare and time-integrated journeys.

- The construction of the rail line in the freeway median sometimes pre-dated the extension of the freeway itself, giving rail a key competitive edge from the outset.

New MetroRail to the south

The next stage of development of Perth’s rail network came early this century with the construction of the 70.5 kilometre Mandurah Line towards the south, along with a short spur off the Armadale Line to Thornlie. The Mandurah Line opened in 2007. Similar to the Joondalup Line, this was partly constructed in a freeway median and designed for wide station spacing and fast journey times. In fact the end-to-end journey time from Mandurah to Perth is 51 minutes, meaning an average travel speed, including station stops, of an extraordinary 83 km/h. This is the same as uncongested car travel times and much faster than peak travel times of up to 1 hour, 40 minutes to Perth city centre.

Prior to the Mandurah Line opening, total Transperth (bus, train and one ferry) patronage was 35.7 million. But after the Mandurah Line opened in 2007, patronage in 2007/08 increased to 42.6 million and reached 56.4 million in the 2009/10.

The Mandurah Line is connected through a tunnel under Perth city centre to the Joondalup Line and runs through to Butler. There are two underground stations in the city centre, one of which, Perth Underground, directly links to Perth Station, used by the three legacy rail lines, enabling easy train to train connections and to buses at the nearby Perth City Busport.

The combined Mandurah and Joondalup line is 111.2 kilometres long and, with the 14.5 kilometre extension to Yanchep expected to open in 2024, it will become 125.7 kilometres long. Which must make it one of the longest urban rail lines in the world within a contiguous urban area.

But wait, there’s more…

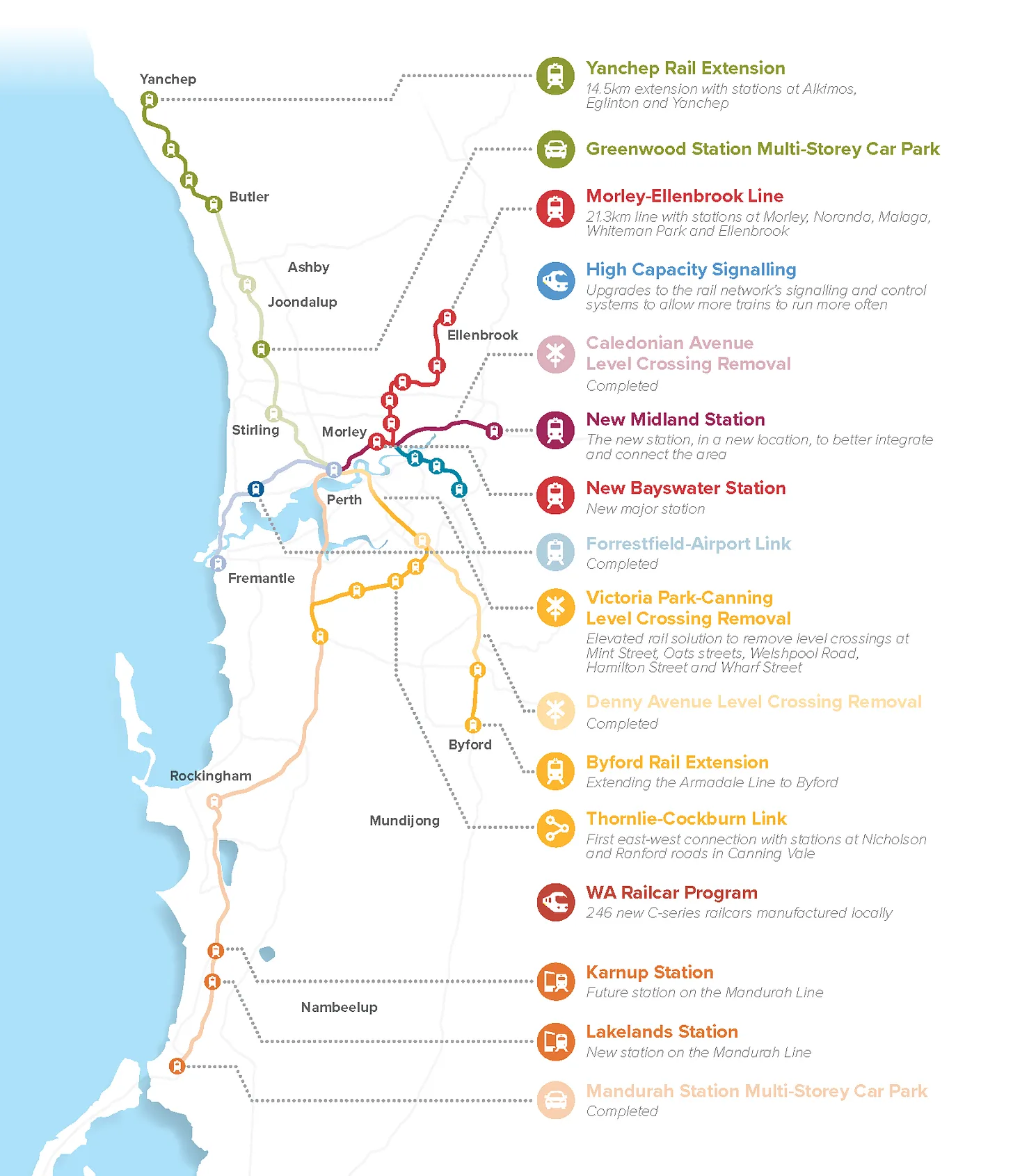

While the level of investment in Perth’s rail network is already sounding pretty impressive, there’s more. Metronet, launched in 2017, will further considerably expand Perth’s rail network. It includes the following projects:

- 8.5 kilometre Forrestfield-Airport Link with stations at Redcliffe, Perth Airport and High Wycombe. Opened 9 October 2022.

- 21 kilometre Morley–Ellenbrook line with stations at Morley, Noranda, Malaga, Whiteman Park and Ellenbrook

- Byford Rail Extension extending the Armadale line eight kilometres to Byford

- Yanchep Rail Extension extending the Joondalup line 14.5 kilometres with stations intermediate stations at Alkimos and Eglinton

- Thornlie-Cockburn Link connecting Thornlie Station on the Thornlie Line to Cockburn Central Station on the Mandurah Line

- High-capacity signalling

- 41 new 6-car train sets

It will expand the Perth rail network by 72 kilometres and add 23 new stations.

Some final thoughts

There is no doubt that Perth was, and to a large extent remains, a very car-oriented city. And its rail network development is a tale in two parts:

A core east-west legacy rail network with closer station spacing serving the older urban core of the city. It provides frequent service to more traditionally transit-oriented parts of the city and is often well integrated with the urban fabric.

A new north south rail network very much designed around getting car drivers to switch to public transport. As such, it is designed for speed and is more akin to a commuter rail model but with frequent service, all-day every day of the week. While bus integration is generally excellent, land use integration is varying degrees of dismal, especially at stations in freeway medians. Joondalup is an exception worthy of note.

The proof of the pudding is in the patronage and this graphic from Greater Auckland tells the story.

There were clear patronage surges after investment in the Joondalup and Mandurah lines but what has happened more recently tells another story. Perth’s rail patronage stalled in the 2010s and then started slowly dropping in the lead-up to the pandemic, while Auckland’s rail patronage over doubled to close to 22 million in 2019. Auckland invested heavily in rail electrification in 2014-2015 and reaped the benefits of the core rail network upgrade delivered in stages between 2010 and 2012. Integrated fares, frequency and span improvements and complete bus network reform (built around bus-rail integration and a strong core of frequent bus service), enabled much of Auckland’s growth while Perth stalled.

But the most striking difference between Perth and Auckland is:

Auckland rail network: 93 kilometre network, including Papakura to Pukekohe, currently closed for electrification work. Only minor extensions such as the short but critical 1.0 kilometre extension to Britomart in the city centre; reopening the 3.6 kilometre Onehunga Line and the 2.5 kilometre Manukau Branch Line. In fact, with the truncation of the Western Line from Waitakere to Swanson in 2015, the Auckland urban network is only about three per cent larger than it was in 2001.

Perth rail network: Legacy 64.8 kilometre network in 1983, is now a 178 kilometre network and will reach around 250 kilometres upon the completion of the Metronet projects. This will be over a tripling of the size of the Perth rail network.

Perth has recovered its pre-pandemic patronage but the clear message is that, for both Perth and Auckland, sustained investment in rail service improvements and bus integration are needed to achieve sustained increases in patronage. Sitting still is in fact going slowly backwards in fast-growing cities like Auckland and Perth. It will be very interesting to see the effects of Metronet in Perth and City Rail Link in Auckland in pushing both cities rail networks forward.

Key takeouts from Perth for any city

- Frequency is freedom. Perth delivers a frequent train network, at least every 15 minutes, all-day every day of the week, supported by an extensive frequent bus network. This is city-wide, not just in the urban core.

- Bus network integration is vital. To maximise rail’s reach and impact, it needs spatial, temporal, and fare integration with buses. Perth does an excellent job with all of these elements.

- Accessibility. Perth’s entire train fleet is fully accessible and step-free for the entire length of the train. This means dignified, inclusive access for all. If everyone can’t easily use your transit system, then you’re artificially limiting patronage potential and excluding people from participation in society.

- Cities grow and public transport needs to grow faster to make a dent in mode shift. Perth continues to make sustained investment in its rail network but also systematically improves its bus network. If public transport isn’t growing in a growing city, then you are in effect going slowly backwards.

Processing...

Processing...

So it turns out you can have good public transport without high density.

You can have good PT without density, but you can’t have great PT without density.

You can – provided it is (as in Perth’s case) frequent, attractive and fully integrated to the extent to which it is competitive with driving.

Bus routes need to be integrated as feeders for higher-capacity transport modes. Toronto has done this for years and it has long been held up as a model of lowish-density development with good public transport.

The UK (outside London) is a classic case of how NOT to do it. There were some good integrated transport systems e.g. (Tyne and Wear Metro) but public transport deregulation in 1986 meant that buses switched from serving the rail system to competing with it.

The UK also fell into the trap of thinking that high densities were a prerequisite for light rail; it’s more complicated than this because density figures can be fudged. Coupled with the UK’s bizarre obsession with bus deregulation and non-integrated ticketing, the result was that very few rapid transit schemes were built in the 1990s and 2000s while the French were rolling out light rail all over the country.

For a good perspective on this, I really recommend ‘Transport for Suburbia’ by the late Professor Paul Mees.

I have been reading a bunch of his papers lately. He was very much about the need for PT to be integrated so that it actually worked for people. Even he agreed that density increased PT use all things being equal but as he then said all things are not equal. The good news is that having lower density doesn’t preclude good PT. But the second good point is it doesn’t mean we have to preclude higher amenity lower density development as a way to provide housing for more people as is so often argued here.

I think it is more an argument that banning high density around stations is a stupid idea.

The point is that a railway station needs a catchment with sufficient potential customers. There are many ways to do this:

1) Dense development within walking distance of the station, plus well-connected walking network

2) High-quality cycling infrastructure for a larger catchment

3) Buses/branch lines/light rail integrated with the rail service

4) Access by private transport (car, taxi, etc)

When used well, this approach delivers a healthy variety of land uses, buildings and densities.

+1

It just costs more. Lower density = longer travel distances, more infrastructure for the same population, economic structure.

It can cost more. But we don’t make decisions based on transport cost alone. We compare all costs with all benefits. If a lot of people don’t take up high density flats in the crowded centre then building to minimise transport costs would be a failure. Perhaps a lot of families opt for low density because they gain amenity in other parts of their life. A bigger house, a garden, more convenience for the majority of their trips, in exchange for less convenience for a work commute.

Are there a lot of empty appartments close to the city centre with decent PT options?

Yeah many people will still choose house + backyard if they are able to.

You get a really limited perspective on this in Auckland though. Options for high density living in Auckland for families are… quite limited (most apartments seem to be small, and the larger ones are very, VERY expensive), and also mostly in neighbourhoods that cannot support an apartment based lifestyle.

Let’s remind ourselves of two key properties of backyards:

1. You don’t need to deal with the street environment to go there, or while being there.

2. It is close enough so you can casually go there if you want, even for just a few minutes.

(1) means even small kids can go there without their parents being required to drop everything and go out on a trip. (2) means they can go there and be there, while their parents are doing any sort of chore, or just about anything else.

‘Street environment’, of course, is an euphemism for ‘car traffic’.

Thinking back of apartments, there are thousands of apartments around Hobson Street alone where, with a small child, you’d need to walk 5 to 10 minutes to get to any sort of park space at all.

You can have good PT without high density, but Perth is still car dominated rather than safe, healthy, fully accessible and low-carbon. I guess it all depends if your aim is a city with better PT options, or a city that functions in a way that doesn’t kill people unnecessarily and that doesn’t kill future opportunities.

Sounding more and more hysterical by the day Heidi

Enlightened and passionate, rather than hysterical, I would say.

You have to design for it, cannot rely on walk up, bus/rail integration is key, extending the reach of stations. Bus routes are integrated with rail and stops are always adjacent to the station.

Good bike infra also extends the catchment: https://www.transperth.wa.gov.au/Cycling

Park n ride is provided too, and is charged: https://www.transperth.wa.gov.au/parking

I would add ‘dependability’ to that list. Part of the continued decline in Auckland’s patronage post COVID is the rail network closes so much people can’t depend on the service existing. Has Perth had the same issues with track maintenance and line closures Auckland has (including a whole network re-build and 3-day weekend closures), and if not, how do they get around it?

I work in this field, in perth, playing a major part in track closures. We had a 30 day line closure recently and provided a multitude of bus replacement services, including peak-only express routes for further out stations, and providing free use of said buses for the worst impacted residents of the line. We see regular line closures due to our long pipeline of works but all disruptions are handled appropriately and effectively. Community consultation is huge in our projects so it reflects when we have to provide those services for the impacted residents. 🙂

Any chance of posting some pix of how the stations work when in the middle of a motorway? Cos that is often used as an excuse of “oh no, we can’t possibly do that” when it is proposed to get the two routes aligned. Including by me in the past !

I guess it is similar to the stations on the Northern Busway? Smales Farm for instance?

Pretty easy to find some examples on Google maps.

First example has train station in the motorway with pedestrian over-bridge to adjacent bus facilities outside the motorway

https://www.google.com/maps/@-32.1250919,115.8575104,458m/data=!3m1!1e3?entry=ttu

Second and Third examples have the bus station on top of the rail station in the motorway median with an overbridge to get the buses in and out of the station. Plus pedestrian bridges for local access and park and rides.

https://www.google.com/maps/@-31.8447385,115.796442,230m/data=!3m1!1e3?entry=ttu

https://www.google.com/maps/@-31.7992325,115.781743,386m/data=!3m1!1e3?entry=ttu

All examples seem to have massive amounts of park and ride as well, which probably says something about the limitations of the feeder buses serving lower density. Would be interesting to know their approach to charging for park and rides.

Friends lived a few minutes from that first example, commuted daily into the city (teacher) including using local feeder bus from that interchange. When I first visited (2009) I was amazed how many people used the rail station and how good the trains were. Seeing them speed past when you’re doing 100kmh in a car is really quite envy inducing.

Next visit (2015) I spent a Sunday morning walking round the new centre, Transit-Oriented Development, that had emerged quickly (coordinated by state development agency) and was amazed to see feeder buses arrive every few minutes in such an off-peak time. I do suspect the P+R is busy and too much of an easy draw, but the local bus network was very good and usable. Certainly demonstrates what is possible in suburbia.

Still, it’s a fair way out in a sprawly city. Our friends (not urban nuts in any way) have moved to Subiaco, one of the central transit nodes, walkable to the city.

Incidentally, Cockburn Central is uncannily like our Westgate/ Massey North / NortWest; old style strip mall to the south of the E-W road, with street-based comprehensive urban development to the North.

And they kept to a heavy rail system for best economies of scale. No point in having a duplication of HR and LRT. Light rail has its place, but not as a long trunk network.

Oh well, Woods is gone and LR to the airport will be history.

Which heavy rail services was the North West and Mangere line duplicating?

I remember way back in the 2004-6 period using Perth as an exemplar, when we were arguing with Treasury and with the ARC about double tracking, electrification, and the upgrade of stations on Auckland’s western line.

While proud of what was achieved on all three programmes in Auckland, Perth’s continued patronage growth shows me how much opportunity for CO2 decrease and patronage mode share has been lost.

Such a good graph.

+1 Great graph.

Also, great diagram of the network, with the proposed extensions shown more vividly.

How bad does that make Aotearoa and Tamaki Makaurau look? I am sure everyone will say that Australia has mineral wealth to fund these projects, but that is irrelevant.

We do not have politicians that are true to their word, and a lot of them still call themselves Labour.

Auckland’s mayor-without-a-mandate is an honestly dodgy businessman who is proud of his obtuse and outdated leadership style, but apparently in favour of heavy rail. Here it seems to be all semantics.

Rail was successful in tram form in the 1940s, for inner Auckland, and light rail will be perfect, for parts of Auckland unfortunately without a rail network.

But Auckland Council and Auckland Transport need to stop hiding in glass / ivory towers and smell the CO2 at street level, which has been killing us for more than a century. It will keep killing us too, and our children, if the extreme weather events do not end us first. But breathing is something the human requires and the science has existed for a long time, so those in power need to stop pretending it has not. As the head of the UN said last year….if your politicans tell you that climate change is not real, they are LIARS. But inaction is as as bad as ignorance when so much research revealed and continues to reveal that fossil fuel private automobiles are the worst invention since Henry Ford destroyed part of the Amazon to grow rubber for car tyres. If you understand history, you understand that the pale man’s pursuit of freedom has always cost the environment, women, indigenous and all other non Pakeha groups. The last generation grew up with the fantasy of the automobile, my generation is stick in between, and the next generation has genuine anxiety because the world is clearly nearing the end of it’s patience with humans. That cars are still allowed to drive into the Auckland CBD is obscene, if we were truly living in a climate emergency there is no war that V8s and other “boy” racer mobiles would be allowed inside the inner city. They are the true danger to children and other less physically powerful groups. Ram raids only occur because a vehicle can access the target. Teenagers are just bored like we all were when we were teenagers.

Society must accept the blame, and stop putting it on the poor humans who attempt to survive the sins of our father, grandfathers, great grandfathers. And men must accept that we are a little bit worse than other non binary groups. Stale pale males on Auckland Council mean stagnation of important future city work, and Auckland Transport seems to import people with experience, but they seem rather stale pale and male too.

But we can still hope for better, and trains seem to be a very good indication of happiness, efficiency, and economic sustainability!!!

I agree. A well-functioning rail-system is a good barometer-reading of how well-organised and cohesive a society is. A rail system depends on co-operation, teamwork and commitment to succeed. If a society that has been gifted a rail system by its forebears cannot successfully sustain that asset, then this is an indication of deeper problems which are likely to affect other areas of that society also.

To do my trip to/from work fully on PT I have to do a bus/train transfer. Going to work it is generally fine as trains are frequent enough in Newmarket. However coming home it is too unreliable so I have given up and drive to the train station. I note that Perth have concentrated on smooth transfers. We have designed our PT system in a way that requires transfers for many people, but then don’t do them well enough.

A North Western rail needs to be an option. There is masses of land north of Auckland at Waimauku and Helensville that provides for decent sized single level child friendly homes for families and retirees. These suburbs have shops and infrastructure already in place, all that is needed is a train service on from Swanson. Then we would not be relient on stuffing people in chicken-coops like these inhuman highrises and three/ two ups that now litter Auckand. Oh, and everyone is encouraged to cycle everywhere. Yeah right, seen the cycleway use of late, that’s happening.

forcing people to live in 2 storey houses. Oh the humanity!

Everyone loves trains, and the cycleways are doing great. Biking is a healthy, joyful way of travelling.

There’s nothing inhuman about apartments – cities have had beautiful multistorey buildings for centuries. What’s inhuman is how cars ruins cities. The roads, footpaths broken by far too many vehicle crossings, the driveways, the carparking. The trauma, the noise, the pollution, the being stuck in traffic congestion.

If you have a read of the work of children’s development experts, you’ll find that the most child-friendly homes are those where families live close to each other and the streets are safe , so children have independent mobility. That’s not a characteristic of suburbia but of urban areas where the cars have been tamed.

The problem with sprawling further is that distances between people and the places they visit grow, so dependence on cars grows – even with the provision of rail.

In Canada Vancouver’s Skytrain is a great example of a light rail system that serves the city and suburbs very well. It helps that there are many high-rise apartments in the downtown area. The city feels alive in the evenings with people on the streets. YVR Airport is included on the Skytrain network.

hi

fine

I want to extend my heartfelt thanks for this significant information. https://monkeymart.online/

This diversity ensures that fans can indulge in their passion for various sports, which might not be available on traditional cable or satellite TV channels.

https://pizzatower.io

For a few hours in 2008 and 2009, residents got an idea of what it would be like to take a commuter train between Langford and Victoria. https://cargames.one

I see a parking lot with cars, I also see a train, but tell me if it is real to play papa’s games in this transporter?

I’ve discovered valuable content here that is definitely worth revisiting. It’s impressive how much effort has been put into creating such an informative and engaging website. – zotabet slots

Many stations on Perth’s rail network are equipped with facilities to accommodate passengers with disabilities, including ramps, elevators, tactile paving, and priority seating, which is really important, because https://igrofresh.com every person should be capable of using such convenient way of travelling.