This is a guest post from Cameron Pitches is the former Convenor for the Campaign for Better Transport. These days he’s the Technology Manager at PortConnect

It should be a surprise to nobody that cars are expensive to own and operate. Obviously they are an inherent part of the road transport system and most families own at least one. In this post I investigate how well private vehicle financial costs are factored into the evaluation of transport projects.

Capital Costs

According to the Ministry of Transport, there are 3,582,246 light passenger vehicles in New Zealand, as at April 2023. That’s a lot of money tied up in vehicles that could be potentially invested elsewhere.

To figure out just how much money, we can get a reasonable idea of the value of the New Zealand car fleet by looking at Trademe. Helpfully, when you search Trademe by price band you get a count of the number of cars in the result. Tallying up the number of cars for sale, in this case from the 7th May 2023, and applying the price band percentages across the number of cars in New Zealand produces the following result:

So we arrive at a figure of just over $109,000,000,000 ($109 bn if you are struggling with the zeroes) currently “invested” in cars throughout New Zealand. That’s a lot. The opportunity cost of this amount, if we assume a risk free rate of return of 5%, is $5.5 bn annually. This assumes cars are owned outright. But plenty of people borrow money at higher rates of interest to purchase their vehicles, so the true financial cost of New Zealand’s private car fleet per annum is much higher.

Operational Costs

So far I’ve only talked about the capital cost of car ownership, but of course car owners also pay for operating costs – petrol, insurance, registration, warrant of fitness and maintenance.

These costs can easily total $3,000 or more per year depending on fuel consumption and other factors.

Use in Transport Decision Making

Recently the Government announced partnering with New Zealand Steel to deliver New Zealand’s largest emissions reduction project to date. This was equated to removing 300,000 cars from the road.

So how does the Government value projects that could actually remove cars from the road?

In comparing different transport projects, it would seem obvious that all financial costs to the economy should be considered, along with the benefits. It makes no difference to a household if transportation is funded privately, or through rates and taxes. Cost is cost.

Furthermore, transport projects that achieve a goal of “one less car” should be able to include the monetary benefits associated with this.

Domestic Transport Costs and Charges Study (DTCC)

I’ve taken a look at two government planning documents to see how these concepts are applied. The first is the Domestic Transport Costs and Charges Study (DTCC). This is a draft document from the Ministry of Transport:

The overall aim of the DTCC study was to identify all the costs imposed by the domestic transport system on the wider NZ economy and the countervailing burdens, including the charges faced by transport system users. Its outputs aim to improve understanding of the economic, environmental and social costs associated with different transport modes, for freight and person movements, principally by road, rail and urban public transport.

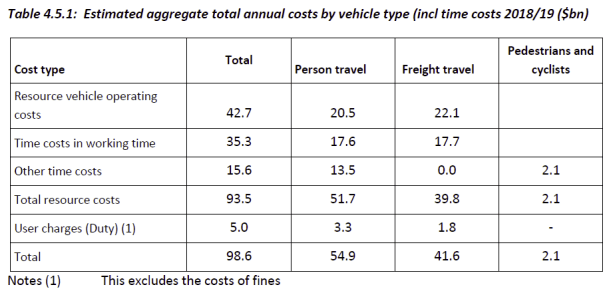

I’m told the final version will be released in a few weeks, but on the whole the report does a pretty good job of cataloguing public and private transport costs. However, I do question the treatment of travel time as a cost for all modes. For instance, on page 32 of the report an estimate has been made for the time costs incurred by pedestrians and cyclists, shown as “other time costs” in the table below.

For many, including myself, time spent walking or cycling isn’t considered a cost as this doubles as healthy exercise, something we all need to incorporate into our day.

Still, the report makes the following useful point:

The economic costs incurred directly by users, amounting to about $94 bn in 2018/19, account for 76 per cent of the total expenditure on the roading system. The indirect costs of crashes and environmental impacts account for a further 8 per cent.

Against these numbers, the costs of providing and operating the road system itself, even on the basis of the desired capital return in place of the lower PAYGO total, are fairly small at about $6 bn or 4.5 per cent of the total costs.

The DTCC includes more analysis on costs of parking, congestion, accidents and other social costs, but at this point let’s take a look at how car costs are treated in the Monetised Benefits and Costs Manual (MBCM).

Monetised Benefits and Costs Manual (MBCM)

This is the manual that determines how benefit cost ratios should be calculated for transport projects and competing alternatives in New Zealand. It is a substantial refresh of the earlier Economic Evaluation Manual.

I wanted to see how the concept of “one less car” was reflected in the cost benefit analysis framework. There must be an economic benefit when public transport, walking or cycling projects result in less car ownership, so I looked to see how this was quantified.

Evaluating Road Improvements

First, here’s the evaluation template for a road improvement project.

You can see that vehicle operating cost savings (SP3-5) are used when considering a roading improvement, but private costs are not considered under the cost of the options (SP3-3).

The implicit assumption here seems to be that users of the road improvement project already own cars and that no new cars are required. There doesn’t seem to be a factor reflecting the need for new users to by a car in order to use the new roading improvement.

Evaluating Public Transport Improvements

Now let’s look at the template for public transport.

Here, vehicle operating cost savings are not listed as a first order benefit, like they are for roading projects. Service provider costs, which includes the capital cost of required buses and trains for example, are included.

The template does refer to Road traffic reduction benefits, however it is a little confusing as this apparently refers to benefits for other transport system users (presumably remaining car users), not new users who have had the financial benefit of ditching their cars.

The MBCM does point out that some 70-80% of new public transport patronage for a new project could come from users diverted from their cars. This should be a huge economic benefit, and indeed p.165 does refer to calculating road reduction benefits using this table:

I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to see how well that $2.99 per vehicle per km has been applied to public transport projects. The original CRL Business case only had vehicle operating cost reduction benefits of $10m, which would seem a bit light if this MBCM framework was applied.

Evaluating Walking and Cycling Projects

The template for walking and cycling projects looks like this:

Again, vehicle operating cost savings to reflect “one less car” are missing here. I would have expected an economic benefit would be applied for this, as is applied for health benefits:

It could be that the “one less car” benefit is applied elsewhere in the framework, but it isn’t obvious.

I’ve concluded that the economic benefits of having “one less car” are not applied consistently across different project types. The consequences of not correctly considering the value of one less car are huge and we could well be significantly undervaluing projects that don’t require a car. Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Processing...

Processing...

Driving a car currently saves me approximately 2.5 hours each day, compared with taking public transport to get to work.

I can earn $200 in 2.5 hours. Assuming I commute 200 days a year, my $5,000 car is earning me $40,000 a year.

Improve public transport, and walking and cycling infrastructure, to make them feasible options and I will switch modes…

Exactly, the benefits to people of owning cars must exceed the costs of $109 billion otherwise they wouldn’t have bought them all. The gains from owning a car would have to be enumerated and included in projects if the costs are included.

That argument requires there to be perfect choice. There isn’t. Almost nowhere in NZ is it functionally possible to live without a car, or at least access to driving. Much car ownership is a positive choice, but much is forced. There is simply no alternative.

We know there is a very high social cost to this, kids food or tank of gas? Many cars are bought on high interest rate loans, then the owner is just one breakdown or crash away from bankruptcy and or losing their job.

Budgeting agencies report that car costs are often the thing that tip households and individuals into homelessness.

Policy is written by and for the well housed and multi car-ed.

Few choices are perfect or evenly balanced. Most are actually boundary conditions. But that doesn’t avoid the fact that if you include the cost of something in an assessment then you also have to include the benefits. If the cost of car ownership gets tipped into a B/C analysis then we would also have to evaluate the benefits that come from ownership like being able to collect sick kids or taking elderly people to appointments or being able to visit regional parks. Perhaps “one less car” reduces utility rather than increases it.

That is a bit simplistic – my Wife and I are able to easily manage with only one car – because I ride my bike and there are ok (not good) buses as a backup option. For out of town travel or less defined routes then we still have access to the car. But if there was no safe cycle lanes and bus routes we would likely own two.

“must” otherwise they “wouldn’t”…

The fuel being burnt by people sitting in their cars letting their engines idle “must” be free, otherwise the people “wouldn’t” just be wasting it.

Except they are. So where does that leave your argument, miffy?

You are free to turn off your engine if you want. Perhaps the cost of the small amount of gas saved isn’t worth the stress of being the dick who doesn’t go when the light turns green.

Modern cars don’t idle anyway. They switch off and restart pretty much instantly as needed or cut out some of the cylinders. Only clunkers idle.

One way of meeting emissions and efficiency standards imposed by socialist conspiracies in Europe and California.

the argument holds that people do what they perceive to “cost” less (money, time, reliability, comfort, and everything else ). It’s a logical fallacy to break down the car trip into just the idling part, but the overall car trip must appear to “cost” less to those who choose it than the alternatives. I’m wasting fuel idling, but i was wasting an additional 3.5 hours a day without a car, and couldn’t travel beyond the timetable of 6am-6pm hourly which was a massive cost both to income and quality of life

The benefits of smoking must exceed the social and economic costs otherwise nobody would have bought all those cigarettes in the first place!

Yes. They must be experiencing something they want to experience or maybe they are avoiding withdrawal and that has value to them. But it isn’t up to you to make their choices for them. If it doesn’t affect you then it isn’t your business to mind. We could try prohibition for things you don’t like but all that has ever done is give money and power to criminals. So yes to your point.

Nice, the take that buying and consuming cigarettes is a completely rational decision is an interesting one. So I guess peer pressure, advertising and enabling environments don’t affect anyone.

I guess the two schools of thought are that ‘people make their own decisions’ and live with the consequences versus ‘people are hapless idiots’ who would be better off if you made all their decisions for them.

It is more that often times, the optimal decision for yourself is quite suboptimal for the entire society. In case of smoking, the smell of second hand smoke is incredibly unpleasant if you are not used to it, so if pubs allow smoking it will cause a lot of people to stay away.

‘people are hapless idiots’ is not a charitable way to put it, but it is well known (I think by now even to professions like economists) that people don’t always make rational decisions.

Well, right now the decision is made for a lot of people who cannot cycle to work due to lack of infrastructure that only caters cars.

People might not be hapless idiots* but are generally really bad at considering long-term effects of their actions and even worse when these effects are more abstract like climate change or pollution.

*Although it certainly seems that some people are trying to prove just that.

I would never have gussed that Miffy is in favour of legalisation of all drugs. Live and learn, I guess.

Haha, just seeing this. It should of course be ‘due to lack of infrastructure’ or ‘due to infrastructure that only cater cars’. Unfortunately, there is really no lack of infrastructure that only caters cars 🙁

goosoid Portugal decriminalised drugs years ago although they kept civil penalties. They have lead the way while we on the other hand persist with the Nixonian concept of filling our prisons with people who have a health issue. Our drug laws are based on prejudice, racism and a fear or hatred of ‘others’. Our laws have made organised crime profitable and prevent people from breaking free or getting help. Yet with smoking we have been successful at giving health warnings, charging the true cost and discouraging young people from falling in to it before they are able to make good decisions.

An interesting experiment is to try living for one day without making the choice that seems to have a greater *subjective* (benefit minus cost) in the moment… it’s absolutely impossible :)))

The subconscious has already made decisions long before the conscious mind realises this.

People don’t buy cigarettes from an objective-societal-benefit viewpoint, they buy cigarettes because in that moment the cost (it’s expensive, they say these things cause cancer, my kid wants me to quit) is outweighed by the gain (oh my god i really want to buy those cigarettes). Some people think more rationally, altruistically or climate-mindedly than others, of course. Others will be short-sighted, peer pressured, or selfish. This is where the analogy ends as lack of cigarettes is just straight up better than buying them, while cars have weaknesses and strengths compared to PT depending on the individual scenario. I think it’s fair to guess people are thinking much more level-headedly with respect to their own costs and benefits about choosing travel methods than they are about purchasing addictive substances.

What a comment made in bad faith.

The article, and CT, are clearly acknowledging the costs/benefits of different options *after* they have been made more viable, and then comparing all that with the current stuff (tho, yes, CT does go a bit deeper), while your comment is nebulous and does neither. It actually doesn’t take that long to install a basic cycling network, and a bunch of LTN’s, for example.

“””

the benefits to people of owning cars must exceed the costs of $109 billion otherwise they wouldn’t have bought them all.

&

The gains from owning a car would have to be enumerated and included in projects if the costs are included.

“””

both assume that those ‘gains’ are not based off dependency/monopolistic policy, and that there have been no generalational populism driving some of it. It also ignores that these ‘gains’ change with the changes. ‘I am saving money because PT times are crap’ belongs nowhere near a business case about improving PT travel times, for example.

It’s like saying ‘vote with your wallet’ and telling people to have faith in that in a current monopolistic sector. Yeah, I can improve my financial situation by getting a credit card with rewards, but to fix collective stuff the government needs to do stuff; otherwise, exploitation of people’s circumstances could get worse (tho, if it is done slowly enough most people won’t notice, hurrah).

This will keep on happening, but I guess it’s alright because we have our 6c off Z vouchers and ‘I’m winning in a crappy system, hurrah’? Would still get it, of course, but everything will also be all collectively fine…

Also, ‘otherwise they wouldn’t have bought them all’ is quite populist. Especially the ‘all’.

But, this is all assuming the 2.5 hours each day. In reality, more than half of VMT is only a few kilometers. So it is a lot more complicated than that, even with our current policies and setup.

Also, ‘exactly’ is quite the bad faith segway to CT’s comment.

> It actually doesn’t take that long to install a basic cycling network, and a bunch of LTN’s, for example.

With all due respect and appreciation for your post, the evidence from my time in Auckland suggests that this is incorrect. I have been waiting years and years and years (decades) for any kind of cycleway or LTN to be installed anywhere in my neighbourhood. So far not a lick of paint, not a single planter box, not a single barrier to separate cars from bikes. And in that time, people have died trying to ride their bikes to work or to the shops. And still nothing gets done.

So yes, in theory it doesn’t take long, but in this case the reality is more relevant than the theory.

Not denying that many people feel driving their car is worth it. However, when you commute to work you travel on your own time, which typically isn’t valued as highly as your hourly rate at work so I think your claimed earnings of $40,000 a year are overstated. Surveys have shown that travel time savings don’t result in employees spending more time at work and earning more. They spend more time with families or doing other stuff like going to the gym.

Extra time with your family is valuable — maybe not in monetary terms, but still valuable. An extra 2.5 hours underway to/from work is an enormous reduction of your quality of life.

Ok, I can calculate it from the other side too.

It only costs me about $6-8 of petrol to get to and from work. Even if the bus/train were free, I would still gladly pay $8 to get an extra 2.5 hours of time back in my day.

Yeah, the system sucks for many people. And the point of the post is to show how this burden on you can be captured and costed – in order to lead to better investment decisions.

Because saving time by driving doesn’t scale. Driving slows pedestrians down significantly. Congestion slows everybody down significantly – and it is created by driving. High levels of driving requires wide roads, big parking areas, wide intersections…. spreading everything apart, so trips are longer. Those longer trips slow everyone down.

I had the same issue finding the capital cost (standing costs) of the vehicle fleet in the MBCM.

I eventually found the “standing costs” are included in the travel times although the detail of their inclusion is not laid out.

This makes sense from the point of view that an option with a smaller vehicle fleet than a do-minimum will have lower travel times and vehicle operating costs, so the change in capital cost will be captured. Its an easy way to deal with the capital costs.

I haven’t checked whether the capital cost of parking is also captured or how. There are about 7 or 8 spaces per vehicle (US evidence). A smaller vehicle fleet also requires less parking.

I’m interested in how car costs are factored for competing projects. I can see how the change in capital cost could be captured in a roading project evaluation, but I don’t think it is captured with competing projects of different modes. The value of a smaller vehicle fleet isn’t clearly attributed as a benefit for public transport projects for instance.

For a major PT project, and if using a gully multi-modal model, the mode shift to PT would reduce vehicle travel times that remain on the road & thus capture the reduction in the vehicle fleet capital cost.

Ok, but in reality vehicle travel times won’t reduce as any extra capacity on the road would be filled by induced demand. For the PT user there is value as they don’t have to own a car to use the PT system. And their household can go from owning three cars to two, or two cars to one, saving thousands per year. That’s the value I’m wanting to see captured.

Hi Cameron, in reply to:

“Ok, but in reality vehicle travel times won’t reduce as any extra capacity on the road would be filled by induced demand.”

– in modelling an equilibrium point will be reached – if new fast PT is provided vs do-minimum there will be a net shift to PT as the relative travel costs now favour PT more (typically models are iterated to convergence to get to the equilibrium point)

“For the PT user there is value as they don’t have to own a car to use the PT system. And their household can go from owning three cars to two, or two cars to one, saving thousands per year. That’s the value I’m wanting to see captured.”

Some of that will be captured by a travel demand model with the remaining travel times for cars reduced and the travel time cost including a capital cost component.

Whether the model captures the full effects of a potentially lower car fleet in this reduced travel time with a capital cost component, depends how sophisticated the model is.

i.e. for the option can the car ownership sub-model also be run to a new equilibrium.

One of the models I worked with did have the ability to do this but we never used it in the mode of having a different car fleet for the option vs the do-minimum.

Its probably something that needs more research to see if transport modelling is truly capturing the full effects.

That’s a long commute!

If your time is worth that much, would you consider moving house?

Just for the record, by car my 10 km, 40 minute round trip is worth about $2 in fuel, and I can do it for $2.40, 40 minutes on the bus plus 20 minutes walk. The car saves $80.00 p.a direct cost plus $5340 in walking by your hourly rate.

Obviously I prefer to bike lazily for 30 minutes at the cost of depreciation on a 25 year old ride, saving a further $3145 p.a.

I don’t live in NZ because it was difficult to live without a car. Can’t fathom needing one being part of my life. Let alone the cost introduced to my budget if I was to get one now.

I’m not sure the trademe sample is valid, it is likely excluding a huge number of very old vehicles that would not be worth selling via TM

Based on $100 billion over 3.5 million cars is an average “value” of around 30K each…

The average age of the light fleet is 14 years, 14 year old cars are not worth 30K…

According to this in 2019,

17% of the fleet were over 20 years old,

and another 14% were over 15-19 years,

29% were 10-14 years old,

That’s 60% being more than 10 years old,

https://www.transport.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Report/The-NZ-Vehicle-Fleet-Report-2018-web-v2.pdf

Good point. So $110bn might be an upper estimate, but the current value of the fleet would have to be close to that as by definition all the older cars aren’t going to be worth much.

The average of $30k is skewed by cars in the higher price brackets. The median price for cars in the Trademe sample is about $20k.

MBCM is designed to be used for comparing and choosing between options for a single project and between different projects in the same funding bucket. It isn’t really intended for comparing apples in one bucket with oranges in another bucket. So it really does take further research and discussion to get to the choice between investment opportunities to decide on social, environmental and economic costs and benefits, to release people and the nation from the burden of unnecessary car ownership. Especially when many people are required to operate a car that the truly cannot afford.

It is worth reading “The True Cost of Commuting” by Mr Money Mustache. The basic point is that commuting by car haemorrhages money.

https://www.mrmoneymustache.com/2011/10/06/the-true-cost-of-commuting/

“…a logical person should be willing to pay about $15,900 more for a house that is one mile closer to work, and $477,000 more for a house that is 30 miles closer to work. For a double-commuting couple, these numbers are $31,800 and $954,000.

If these numbers sound ridiculous, it’s because they are. It is ridiculous to commute by car to work if you realize how expensive it is to drive, and if you value your time at anything close to what you get paid.

I did these calculations long before getting my first job, and because of them I have never been willing to live anywhere that required me to drive myself to work. It’s just too expensive, and there is always another option when choosing a job and a house if you make it a priority.”

I think this is one example of why being poor is by itself expensive.

If you already are able to raise enough capital to buy a centrally located home, then you can do this, and that investment will pay its dividend in the form of less commuting costs.

If you are not able to do that you’ll have to suck up the ongoing cost of commuting.

If there is some tip for saving a lot of money, but you don’t see a lot of poor people doing it, you should be sceptical.

One solution to commuting and housing costs is to combine the two under one asset.

How many wealthy people are sleeping in their cars?

Many people are poor in NZ because they buy into the “kiwi dream” of a house and a piece of land, when they might be served just as well by a centrally located apartment for a much lesser price. The fact that lengthy travel to the “kiwi dream” is subsidised by everyone else makes that “kiwi dream” affordable. $1600 of my rates goes to facilitate inner city driving and parking. Then another chunk goes to pay the interest cost on AT transport assets that don’t produce any meaningful return.

Then a whole chunk of my taxes goes on motorways when my use of negligible.

The unfortunate thing is that expenditure on roading is mostly for the benefit of the wealthy who do the most driving. Oh for road tolls where the user pays.

> they might be served just as well by a centrally located apartment for a much lesser price

But in NZ all the centrally located apartments are crap.

And a decent sized one costs an arm and a leg. And that’s before you get into the leaks, fire issues, body corps, etc. Not exactly sure where that fits in with the ‘kiwi dream’ either.

I would gladly raise my family in an apartment if it were of the same quality as a mid-80s (or newer) central Europe apartment (double glazing, thick insulated exterior walls, no noise from neighbours, shared garden, shared laundry).

Unfortunately most apartments in NZ are surrounded by carparks, cold (or too hot), thin walls, antisocial neighbours.

For all that I love to argue for public transport and increasing mode share for active transport (walking and cycling), I am not sure that sustainable transport advocates are living in the real world. We might think that using a car or using a bus or bike is more or less equal as a means of getting from A to B, but that leaves out the personal identity and pride of ownership as a part of car culture. Being able to say, “this is my car,” actually means something to many people.

Secondly, there will be some of us for whom walking and cycling will always be a second choice, if they are possible at all. Now that I’m in my 50s, I find that I use taxis or (heaven forbid) Ubers to go the short distance from the pharmacy or supermarket because I am either too tired to walk or I simply have too much to carry. In that context, advocating for walking and cycling is ableist, and there should be parallel advocacy for e.g. mobility scooter users, who need safe spaces to manœuvre at a fast walking speed.

You mean, like mobility scooters using cycle lanes?

I am perhaps lucky well into my 60s to be able to walk and carry stuff, but my body hasn’t been ravaged by the excesses of capitalism. Perhaps it is because I have walked and been mobile that I am able to be active and seldom get tired.

But carry on as you are. A few others will worry that there won’t be a polar ice shelf in 10 years if the current emissions trajectory continues. Have the floor plate of your mobility scooter lifted so your feet don’t get wet.

Interesting post thanks.

Due to a difficult personal time, I decided to investigate how little a person can actually rely on anything other than a bike and an AT Hop card. One Sunday I walked to Huia as there is no bus beyond Laingholm. But apart from that, I have visited Maraetai, Long Bay Beach, Wattle Downs Beaches, and all with either the physical pleasure of riding a bike, or the relaxed sitting position of not piloting a large vehicle. For your well being, regardless of the financial cost, giving up driving a private motor vehicle will be the best decision you ever make in your life. I know that most are burdened by children that need to be moved etc, but there are electric cargo bikes, and buses accept children potentially straight from the hospital of birth (train if you are born at Middlemore I suppose). It is a far too simple equation, with, or without the numbers!!!!

The compromise is not having to “give up your car”, it’s just to not be forced to use it for every single journey you need to make, to have other viable options.

You can, but at the moment you’ll have to accept a very unreliable public transport network (I think cars are literally 100× less likely to fail than PT at the moment), and when cycling, a level of danger, both perceived and real, that most people are clearly not willing to accept.

Yes, it’s very simple if you ignore the value of time, which is the one thing people can’t make more of. Either your time is close to worthless, or you fail to understand that not everyone can spend hours more a day on a garbage PT network or riding bikes and still cover off the things they need to get done.

‘Giving up driving a private motor vehicle will be the best decision you ever make in your life’

You are just as out-of-touch as everyone who says that cars should be the only form of transport.

Private vehicles are a financial and spatial burden for city commuting, but they are one of the best enablers for outdoor recreation ever invented.

After the week is over, I can just get in the car and go where I want. In half an hour I will be free from urban congestion and can have an enjoyable drive to whatever corner of the island I desire to be in, all within a few hours.

Many people fail to understand that people LIKE driving, they LIKE cars, they just don’t want to be forced to use them every day for lack of practical alternatives. My dream would be for my car to retire from commuting duties and just become a recreational tool/toy.

But giving up cars altogether would make my quality of life instantly worse, and the same would be true for most NZ families.

Cars? Worth every dollar.

Interesting article. I’ve worked a bit in these sort of analyses and it gets very tricky!

People switching from driving to another mode are presumably seeing some benefit from doing so, but it in most cases that benefit is unlikely to be the full saving from not owning/operating a car – i.e the benefit is less than the existing private cost. For example, because I ride my bike we don’t need to own a second car, but sometimes I get wet or cold and some trips take longer (though many are quicker!), so my net benefit is a bit less than the vehicle savings.

The real huge benefit of shifting trips out of cars is the reduction in *social/external* costs. Because drivers don’t pay these directly they don’t factor them into mode choice. But if someone sees a tiny personal benefit to ditching the car they will probably change, which means their total private “costs” go down a tiny bit, but *all* the external costs of car usage go away. So no air pollution, crashes, congestion, or noise from that car. This is likely to be much larger than the net personal savings.

Este artículo esclarecedor y estimulante en un blog investiga los gastos ocultos que conlleva ser propietario de un automóvil, más allá del precio de compra. El autor indaga en las ramificaciones monetarias, ambientales y sociales que conlleva poseer un automóvil, examinando aspectos como el costo del combustible, el costo del mantenimiento, la congestión y el impacto en la planificación urbana. El propósito de este artículo es generar conciencia sobre los mayores costos y efectos de depender en gran medida de los automóviles privados, y alentar a los lectores a pensar en opciones de transporte alternativas y participar en debates sobre movilidad sostenible.