This post contains two guest posts from readers, both of which were sent to us after the flooding on Friday 27 January, both of which discuss how we handle our stormwater.

This is a guest post from Ed Clayton, who’s written for us before about Auckland’s relationship with freshwater, the potential for green-tracking light rail, and creating ‘green density’ with Ecological Build Zones.

I’m writing this two days after Tāmaki Makarau received more rain in one day than it usually does all summer. The Fire Service reported that every single vehicle was mobilised in response to the flooding. MetService has just issued another warning for rain over the next 24 hours and NIWA has predicted more moisture-laden tropical air making its way to us for the next 5 days. It’s just started raining again outside.

Flooding has been so widespread that it’s likely this will be the costliest natural disaster for Auckland. Climate change has exacerbated the floods, as warmer air can hold more moisture. I’m certain that insurance companies will be taking a long hard look at how extreme house prices will be influencing claims, along with a new affection for Auckland Council overland flow paths.

The flooding was so bad because Auckland has built over far too many of the small streams in the city. We’ve removed the ability of streams to cope with large volumes of water by building on floodplains and removing the hydraulic connectivity that is crucial for managing flood flows. Hard, impervious surfaces remove the ability for water to soak in, instead funnelling it straight into our stormwater system. And this carries with it the detritus of our urban spaces, resulting in pollution and closed beaches.

Wairau Valley is a perfect instance of this mistreatment, concrete-lined channels and pipes cannot cope with extreme deluges and so roads flooded, houses were swamped, cars swept away and tragically, people died.

However, where newer developments have been designed around more water-sensitive designs, flooding was minimal. A great example is how Hobsonville Point coped with the rain.

Whoever designed the stormwater system in Hobsonville Point can take a bow. Over 300mm of rain in 24h in a densely built area and last night there was only surface flooding on some roads. pic.twitter.com/1UkYAZbCiu

— Aaron Schiff (@aschiff) January 27, 2023

What can be learnt from this storm? A lot, if we want to, but as evidenced by Alec Tang, we haven’t learned much from the last one. It’s great that our new subdivisions get raingardens, swales and biofiltration devices, but for the already-built parts of our city, more is needed.

https://twitter.com/AlecTang_/status/1619289087453851648?s=20&t=q400xZW5AhwKY9jFZF1xqA

This post then, is a call for a new perspective on what water means for Aotearoa. We’ve just learnt the hard way that all infrastructure is water infrastructure, and this means we need to re-evaluate how and what we build. I’m advocating for all infrastructure to be assessed through a water-lens; how does this apartment building improve water quality in the local stream? How can we increase transport links and community connectivity while removing flood risk?

I’ve had thoughts about this for a long time, and I’m subscribing to ideas of ecological net-gain. This is also what Te Mana o Te Wai (in the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management) sets out to achieve through recognising we have an obligation to improve freshwater for future generations. If we build something, it must improve water quality. No more offsetting or mitigation of effects. What this looks like in practice means that, over time, we gradually improve all of our infrastructure. This could be designing light rail to have green tracking, purposefully built to infiltrate and treat adjacent land use runoff. It could be creating ecological build zones that grant bonus development rights to buildings that incorporate green roofs.

It most definitely needs to be catchment-oriented planning that is a collaborative process with mana whenua. As we increase our urban housing density, we should increase our urban green spaces. Think pocket parks designed as stormwater detention, but that are social spaces when dry. Identifying where our overland flow paths are and buying properties to create linear wetland parks designed to flood and store water. Utilising concepts such as the Sponge City. Daylighting our buried creeks like Waihorotiu to create more spaces like Te Auaunga. Reducing and redesigning roads for private vehicles so that as we reduce our impervious cover, we also change the function of roads, encouraging them to become ecological links.

The ultimate goal of this should be to reintroduce quality green and blue spaces back into our neighbourhoods. We need to change our perception of stormwater away from one of nuisance, to one of resource. This is the 15-minute city, but reimagined as access to local swimming holes with great water quality, sources of mahinga kai, wetlands, native bush and streams that are biodiversity hotspots in our city. We know the mental wellbeing benefits of being close to nature, and by placing water outcomes first we can start to create a city that improves wellbeing, is climate resilient and equitable.

None of these changes will be easy, and I’m sure there will be many detractors (“Kiwis love their cars”). Much investment will be needed too, but as we find out more about the cost of this event in the coming weeks and months, can we afford not to?

This guest post is by reader Anna

Too much rain, not enough drains

First up, I am so so sorry, beyond what I can put into words, for those who have lost their lives, their livelihoods and their lifestyles over this awful Auckland Anniversary Weekend.

Yet I think that it makes perfect sense, because it matters, to ask: what could have been done to mitigate the awful impact this rain has had. Because the problem is not just too much rain. The stormwater drainage system in Auckland has failed to cope, and failed the poorest areas of our city worst.

While this rain is unlike anything Auckland has seen before, it wasn’t completely unexpected.

Auckland Council’s current (2021) Long Term Plan says:

We can’t continue to use the past to plan for the future – due to climate change, many of our natural hazard risks are not fixed (e.g. the frequency and intensity of storms in our region is expected to increase).

Those words were put on paper in 2021, but the science behind them has been settled for at least a decade. Auckland should expect more rain, and it follows that we should be looking after our drains.

Looking after infrastructure assets is a famously dull topic – in the words of John Oliver “If anything exciting happens, we got it wrong”. Did Auckland Council get it wrong?

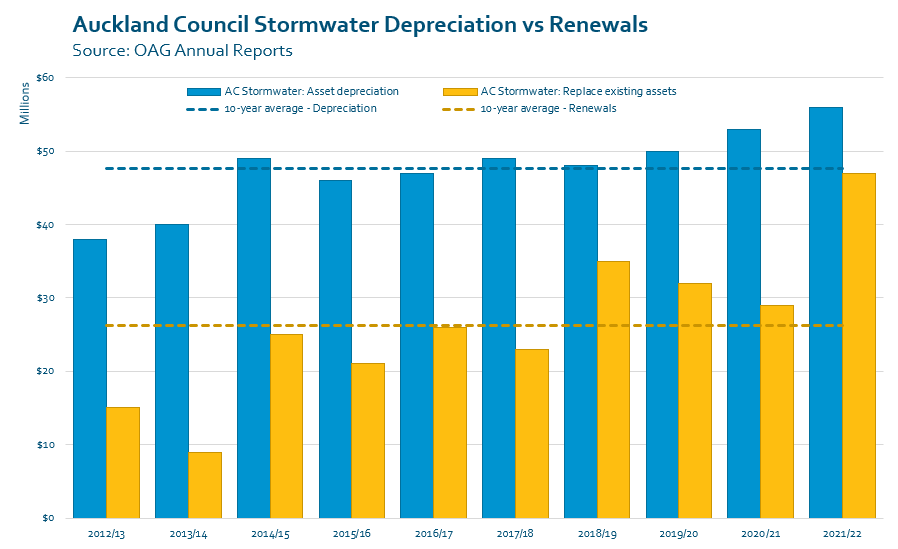

One measure of whether infrastructure assets are being well managed, used by the Office of the Auditor General, is to compare renewals (which Auckland Council calls “replace existing assets”) with depreciation (the loss in value of the assets, from being one year older). While both numbers can vary up or down in a given year, in the long term the two numbers should average about the same. The OAG reported that nationally, across all assets, local council renewals in 2019/20 was 74% of depreciation and concludes that this “indicates that councils are not adequately reinvesting in their assets.”

So – has Auckland Council been adequately reinvesting in stormwater assets? Both depreciation and renewals for stormwater are published each year in the Annual Report. It’s a very dull job trawling through the fine print of ten Annual Reports to find these numbers, but who has anything better to do on such a rainy day? Here are the numbers.

Over the past ten years, Auckland Council’s spend on replacing existing stormwater assets has averaged 55% of depreciation.

The OAG report goes on to say:

If councils continue to underinvest in their assets, there is a heightened risk of asset failure and resultant reduction in service levels, which will negatively affect community well-being.

Many Aucklanders will have other words they could use, at this time, to make that point.

Processing...

Processing...

I am really worried that this mayor will use the budget pressures to reduce funding for active modes and public transport, because “we can’t afford those luxuries right now”. So the transport modes that damage our climate least will get shafted again if there is no pushback from other councilors.

But yeah. Cancelling 10-15 cycleways will give you… maybe one large-scale new stormwater project? Plays well on some talk radio stations, sadly.

I mean, the drainage improvement costs alone on the Pt Chevalier to Westmere “cycleway project” (actually a road upgrade and remediation) that Mike Lee and Co are currently trying to stop are more than the cycleway costs in the same project. But hey, do facts matter?

https://www.greaterauckland.org.nz/2022/12/09/weekly-roundup-09-december-2022/

Two great contributions. Thanks.

Anna, thanks for those figures. 55%, eh? And it’s worse than the national average. Well. That’s a complete failure on the part of our decision-makers. They have failed to responsibly interpret and communicate to the public, that the call for low rates is impoverishing this city.

It’s time for this to change. The local government act requires the council to plan for future generations, regardless of any head-in-the-sand politicians. We need accountability.

“. As we increase our urban housing density, we should increase our urban green spaces. Think pocket parks designed as stormwater detention”

And this is one of the most apparent issues with the current 3 waters proposals, Decisions around storm water will become removed from territorial authorities and invested in ultra-regional bodies,

Additionally many stormwater “sponges” – open green spaces golf courses, playing fields, etc (and potentially in the future transport corridors) will be in some jurisdictional middle space with no clear delineation over who has the power to make policy or developments in the area…

Either stormwater should be left with local TAs or

the 3 water entities need to be expanded to have power over stormwater “sponges” and the planning of them in the future…

This is a good point. The argument for including stormwater in these large entities has never made sense, when stormwater isn’t about pipes, as much as it is about land-use planning and green spaces.

It’s a shame that so much of the 3 Waters opposition has been based on racism and spurious claims, because there are actually genuine issues with what’s proposed – like you point out.

“The argument for including stormwater in these large entities has never made sense, when stormwater isn’t about pipes, as much as it is about land-use planning and green spaces.”

Uhm…. why do you feel a stormwater engineer can’t do ponds and wetlands? They already very much do as part of their normal job (just not to the levels – pun intended – we need). The related ecological VS engineering approach discussions by no means necessarily need another agency, just the right policies and direction.

So I think a 3 waters combined agency can be perfectly the right agency to do this (discussions about whether or not the govts agency sizes proposed for NZ are the correct size aside).

Where I live we have state highway 1 cutting many of our towns in half. We have seen what it is like in a lower population district trying to get a national organisation to prioritise projects in our area.

We don’t want to have to go cap in hand to a national board to get work done on our water systems. Auckland isn’t the only area that has to cope with flooding.

Nothing racial in my dislike of 3 waters at all.

Is it an issue with the current 3 waters proposal? Apparently Auckland Council are underinvesting in storm water (55%?!). 3 waters would fix this as storm water depreciation funding would not be used for something else.

Auckland Council are not doing the job right now so why assume they will do the job in the future?

Why would you assume a 3 waters entity would do better. Faced with the choice of small communities without clean water to drink and Auckland flooding from time we can expect they will spend the money on drinking water.

The real problem is flooding is mostly a local issue (unless you are Waikato, Canterbury or Otago), polluted beaches are a local issue. It makes no sense to hand those local issues to a huge entity.

Even drinking water makes little sense. Auckland has successfully dealt with it as a region.

I do not agree with 3 waters neverless expanding the organization. All we would be doing by introducing 3 waters is just centralizing bureaucracy growing the government bigger. For Auckland region under 3 waters they would need to look after an area of Pukekohe to top of New Zealand, as a result will any focus be given to people in Northland? My prediction under a 3 water system of water assets will be after collecting a fee on water usage the money will just all be spent on Auckland because that where it growing while areas in Northland will continue to get neglected. Also the tactic of 3 waters may lead to privatization of water assets, that what happen with electricity it was under govt control and then most assets were sold off to the private sector.

Going through new house due diligence atm. The LIM reports identify flooding in the area to a certain extent, but not the property itself. But how old is that data? It’s a relatively new subdivision, so do those flood risks reflect the stormwater infrastructure since put in place? Is it still fit for a post-1.5 world? What about the rest of the suburb as it gets built? Will they now need to revisit the stormwater provisions? What will that mean for the first tranches of houses already built?

We are only starting to talk about managed retreat at the coastal level but I’ve reached the end of my layperson’s ability to understand the information currently available. If the expectation is that people make an informed choice, we need to accept that currently that is easier said than done without a civil engineering background. That will need to change.

I went and visited the area when the rain was falling on the 27th. There was no standing water at all in the street, so it looks like the drainage is pretty good. But am I vulnerable to a knee-jerk algorithm-driven change in insurance risk levels, or the flood plains, as a result of the most recent downpour? Will it be ‘tough luck, should have known better’ if I get left with an uninsurable house?

Similar / same. Except I’m in Christchurch. If you get a chance I recommend having a look at the flood risk map for the north / east of the city. Place is mostly flood plain.

https://ccc.govt.nz/services/water-and-drainage/stormwater-and-drainage/flooding/floorlevelmap/

The council has been doing a lot better than others though. There have been major joined-up flood mitigation schemes. New pipes, large detention basins to intercept incoming water that have made real big improvements in the existing urban area. This was spurred by a couple years with multiple flood events that made it into houses multiple times. But the latest noises are that it’s more important to gut these programs to save rate rises for a couple years. Memories are very very short it seems. Oh and spend any capex on a billion dollar stadium.

My concern is being left with an uninsurable house, from the perspective of a mortgage. I plan on buying a new build, having reasonable flood mitigation measures built in the house (solid ply sheathing, built up higher than required, concrete flooring, most storage on the second floor etc etc). And having investments in other (actually productive) assets rather than my house. But my concern is that we’re required to buy into this housing ponzi scheme, and therefore have to get a mortgage which requires having insurance, which could well become insanely extortionate as you have to pay out for neighbours much more fragile houses.

And even with no mortgage, the issue is if the council comes and stickers your house, or the govt redzones your land and deems that they can boot you out with no compensation, and puts you out on the street. I understand having no insurance means you should not get a payout, but if we are allowed to play the individualistic game, then you should not also be able to be forced out like some kind of “greater good” scheme that only makes your situation worse.

Ummmm, that’s not how it worked in Christchuch (see link below). It’s extremely unlikely that any red-zoning would be without compensation.

https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-announces-new-red-zone-payment

Whether the compensation would be sufficient, whether it will convince people who don’t want to leave, whether – if the issues spread wider and wider – we have enough money to keep compensating at “sufficient” (see above) levels? All fair questions. But nobody is proposing to boot people out by declaring their land forfeit (that only happened to Maori – and hopefully that kind of injustice is past).

What is much more likely to happen is that the govts and councils of the future will, exactly because of the compensation issue, NOT red-zone. And then the people who can move, move and sell at a loss – and eventually floods and the lack of insurance will eventually do the same job for the people who remain, in much more brutal ways. That’s climate change for you.

I think you vastly overestimate the ability of younger Kiwi families to just ‘move and take a loss’, considering the enormous portion of your working life that a mortgage now requires you to commit to paying it down.

Given the huge obstacles in our generation even getting a house in the first place, the solution is going to have to be a lot better than that.

Buttwizard – while I agree with you, I think you’re underestimating societies willingness to let the few take a massive hit rather than the collective take a much smaller hit.

“I think you vastly overestimate the ability of younger Kiwi families”

I am not estimating anything – I am responding to Jack’s implied (or more than implied) statement that NZ would *retrospectively* prohibit living in an area without compensation. That would be political suicide. They will either pay compensation (act, at high cost to rates/taxpayers) or simply let the matter fester longer (not act, also at high cost, but to others).

I specifically said that whether or not compensation (where it is paid) will be “sufficient” will be a big question. I also didn’t say anything I can see about that it would not it would be a massive – possibly devastating – blow to have to move.

“I also didn’t say anything I can see about that it would not it would be a massive – possibly devastating – blow to have to move.”

Ah, apologies, cart before horse on my part.

I genuinely am unsure about how we address this in an urban context, given the huge push-back in coastal communities about managed retreat. If we can’t manage that, then what hope do we have in sorting out a workable solution for suburban areas that end being functionally uninsurable, or at worst red-zoned? At least in coastal communities, the cost of infrastructure may see services withdrawn and hands forced, but that’s a different proposition in intensified, inland urban areas.

Firstly, my mistake, Gurf you’re technically correct. And that was what finally happened in the end. But the intent of the government for years was not far off, and only changed after a change in govt.

The redzoned residents who did not have insurance were intended to get next to nothing. All services would eventually be terminated to their address, no road, sewer, electricity. Not allowed to build anything else. Sure govt would still “buy” the land at todays value, next to nothing because…. its worthless on the market. But that’s getting very close to dispossession in everything but name, and is the argument the owners were making in court before the govt settled.

And that’s putting aside the stickers that actually do remove you.

Buttwizard, overall I think the goal of the government should be to wind down the value of homes / land. Implement a ratcheting land tax, and maximise housing supply in safer areas, and build infrastructure there.

A large part of the issue comes from the enormous value of property. People invest a decade or so worth of disposable income into something, and that makes every action from the govt extremely expensive.

As part of your due diligence you could and probably should hire an engineer (probably a stormwater or environmental engineer or similar…not necessarily a civil engineer; anyway they need to be doing this kind of work already to have the expertise and access to the expensive software) to visit and build a model of flood risks, with a range of annual return intervals and climate change scenarios. And also consider impacts of increased impervious surface coverage in the catchment and anything else they can think of which could improve or worsen flooding risks and impacts. You will probably need that modelling anyway, if you plan to apply for consent to build anything in the future. And it would be useful in arguing insurance premiums if you were subjected to an algorithm-driven change. I don’t think it reasonable to expect to be able to do that modelling work (nor to some extent the reporting and interpretation) as a layperson, just like I wouldn’t expect to be able to knock up a building or do the conveyancing, or anything else that people study as a profession.

While I agree that would be the most prudent thing to do from a risk management point of view, by the time one gets a LIM report in the conditional offer process, you generally only have a few days at most to actually decide to proceed based on what it has in it. I’ve snuck a few days out of the process by reviewing the flood maps before we put our offer in (checking for tsunami risk, pre-the downpour, ironically) but again, as a lay-person.

The odds of me turning around a separate piece of commissioned engineering work before the conditional offer deadlines we have set are nil, even if cost was not an issue – which it probably would be. At that point you are left wondering ‘what is reasonable?’ to expect people to do when it comes to due diligence.

Have checked the flood maps – property not affected directly.

Have checked the property during 200 year event – property and surrounding area not affected.

Have obtained insurance quotes showing the flood risk is deemed ‘low’.

I feel like as far as due-diligence goes, that’s probably as far as you can reasonably expect people to go.

Separate civil engineering reports outside of this process are starting to get into ‘information overload’ territory, and generally make you question whether you are doing the council’s work for them in checking for what would be Unitary Plan-level failure.

Agreed. At some point – especially if you have to do due dilligence for multiple properties before you manage to buy one – its just ridiculous. Macro-scale flooding risks (i.e. a whole street or a suburb) shouldn’t be the indvidual buyer’s job to look at.

As I said above, it’s probably pretty easy call to make for 70-80% of the properties whether they are at risk or not. It’s the edge cases that are the problem. In a way, having no flooding in the last couple weeks is probably a pretty layperson’s good acid test.

Agreed it is quite expensive. I wouldn’t want to spend the money unless I had a contract agreed, subject to my due diligence. But it’s cheap compared to the losses which might result from not having it.

Also agreed that it would be hard to get it done in a typical due diligence timeframe…but in the current market (a buyers’ market) vendors might agree to a longer timeframe.

(Note: a vendor might even want to get something like this done and provide it to potential buyers, if they felt that some buyers might be put off by flood risks, that they felt were very small or non-existent).

Isn’t building more stormwater assets,a bit like building a larger rubbish dump. Surely the answer is to mitigate the flow at source. The reluctance of the whole world to “embrace” climate change, takes the best option off the table,so then how do you deal with the rain on the ground,is the best local authorities can do. The moar roads (larger pipes),will seem the obvious answer,replace rain drops with cars,gives you the answer.

Auckland has to stop pussy footing around with 2/3 storey residential development, these are more environmentally destructive,than the single houses they are replacing.

Will it take insurance companies to drive ,where we cannot build,or will we see courageous leadership from our civic leaders.

Such courageous leadership would free up tracts of land for improving Auckland,s livability,water doesn’t listen to any one’s opinions, it goes where it goes,fight it or embrace it are the options.

“Surely the answer is to mitigate the flow at source.”

In the sky?

Kidding aside, there is no “point source” for rain. It accumulates. It grows, there’s a sliding scale, until eventually, some way downstream, it just gets too much. Can you intercept it? Yes, but usually not with 1-2 localised mega projects. That’s old-style thinking and even more expensive (and potentially destructive). At the volumes we are talking about, the only retention you can really do is effectively big lakes, or (very wide) streambeds. Either takes a lot of land.

In new developments, Council is now (even before the last month) asking for more ponds etc. That will only increase. Developers hate it, but in the end they can put the cost on the new houses.

But in existing residential areas? Well, look at the low-lying areas, the areas close to streams etc. I think it’s not THAT hard to figure out which areas are most endangered (even without the examples of last week). We will never be able to rectify all endangered areas anyway, so we need to concentrate on the worst-endangered ones, and those would surely be pretty clear to identify?

What is difficult I think will be “Who will pay for removing those houses and turning these homes into stormwater overflow areas?” and “What if people DON’T want to move?” Do we actively red-zone some areas? Or do we wait until floods and insurance companies force the remaining people out?

Te Mana o Te Wai obligation to improve freshwater for future generations is a bit like the Cathedral thinking discussed in the below podcast which is about constructing a built environment over the very long term (think decades and centuries not years) that shares prosperity and the responsibility to address and adapt to climate change with not just the current generation but future generations.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/0yseYEbbAQhcePsIzO4BPC?si=1efOzLDhQFezT2xFeuqzYQ

P. S I have concerns that Te Mana o Te Wai is an abstract concern that is discussed (and perhaps in part justifies enormous planning or cost benefit analysis) but is not implemented.

Sea level rise and climate change will affect many parts of low lying Auckland.

The Mangere inlet at high tide is not much below road level and at high tide a storm in the area could well wash large waves over Otahuhu, Mangere and Onehunga.

One line of protection are the Mangroves that are growing strongly. They store carbon, reduce erosion and are important places for crabs, shore birds and small fish.

Kelp and seaweed in both the Hauraki Gulf and Manukau harbours are gone. They can store huge amounts of carbon. Crayfish in the Hauraki Gulf are functionally extinct. Crayfish normally feed on kina but without them, kina are taking over the area and destroying the kelp forests which used to flourish.

We must stop dredging. Any dredging of rivers, harbours or sandunes undermines nearby coasts as any child digging holes in the sand will know. Stop Auckland harbour and other harbours such as Bluff, Lyttleton and Tauranga. We must stop dredging the sand dunes at Pakari and Mangawai. They are the first line of defence against storms and swells.

Intensification is one of the best ways to reduce climate change for several reasons. One being theat less sand is required for buildings and sprawl. Auckland makes huge amounts of concrete and quarries are making big holes in places that the public don’t know about. There are sand wars in many cities in the world where beaches are disappearing.

oops …stop dredging Auckland harbour and other harbours,,,

Sadly Mr Fix-it and his gang of slashers think what he has to fix is the city’s balance sheet to match an artificially lowered income. Whereas what is needed is fixing the city, which sure many voters thought it meant, ruggedising it for the new normal. This of course requires investment not cuts.

This storm has shone a harsh light on how impoverished and impoverishing this UK-style ideology of austerity is for any government.

Lot of his voters believe that the money is there, it’s just being spent on projects they think are ridiculous [I won’t start by naming them], or the wrong parts of the city.

In reality, even if one agreed to can all those projects they don’t use / like, it would be a drop in the bucket. The vast majority of Council’s spending goes into nuts and bolts everyday infrastructure (building and maintaining), and in turn, this costs massive dollars. You can’t “do more with less” in those areas, and cutting back “luxuries” (which only your own subset of voters consider luxuries in the first place) means the austerity effects are all the harsher, while at the same time not freeing up enough money to fix the actual problems.

The only way we could fix those issues would be with rates rises and changes to the way we develop our cities (low-density development with medium-high capex and very high long term opex). But that’s a long term fix that many of those voters don’t want to see. That would mean less money for their Coromandel beach house. Oh, got to rage against NZTA for still not having re-opened the roads…

A lot of council money goes on transport which really should be user pays. A sensible move would be for all transport to be paid for by fuel tax etc, that would free up a huge chunk of money for councils and get added environmental and congestion advantages (people will drive less if fuel is more expensive). If only it wasn’t for those pesky voters.

Right wing Twitter: “Lets start with charging those cycling freeloaders then!”

[Yes, I am still grumpy that in my very short fleeting look into Twitter during the floods and days afterwards I saw several tweets claiming that the floods were so bad because Council / At / Phil Goff had been “prioritising” cycleways instead of “important stuff”.]

Gurf: Yes that is ridiculous. Although those tweets were actually correct: had AT reprioritised road space to cycling instead of building expensive cycleways they could have spent much less on cycling and also had a much bigger cycling network. I am sure the tweeters didn’t actually mean that though.

Maybe the Mayor needs to play SimCity 2000?

“YOU CAN’T CUT BACK ON FUNDING! YOU WILL REGRET THIS!”

Why not widen those existing small streams? Take that one in the picture, how much effort to make that twice as wide?

We have a lot of those streams near us and all the houses either side got slammed. If they had twice the capacity the damage would have been much less. Get the diggers out there tomorrow instead of spending the money on some long term planning document that will never get built.

See those fences in the picture? In most locations those will be the property boundaries. So you need to buy land. That land is unlikely to be for sale – so forced sale (Public Works Act) processes. Then you may need to buy the whole property, because you may end up undermining (maybe literally) the viability of the rest of the site…

In some places, like Underwood / Walmsley, there is enough space, and it’s easy (still cost $25m!) but in many others it is not easy (anymore).

So in short – yeah, lets do it, and start with some easy ones where we have them. But in many places it’s far from easy. Urban areas are complex. Only autocratic states can “cut through red tape” easily.

Related question – where is the Wairau photo taken from? I can’t find it on an aerial and am not a local.

Looks like McFetridge Park

Thanks – finally found it. And yes, in that location JimboJones’ suggestion of a quick improvement looks actually feasible. For about 200-300m total distance before and after the shot, assuming there are no leases with the sports clubs etc in the way, and no services in the ground which would be in the way, and if there’s no protected trees. But yeah, that corner to the left would possibly be a good spot for a wetland.

Beyond that, it snakes back into industrial land. “Snakes” might in fact be too meandering. It looks like a 2000s Nokia “Snake” game with long straight lines of creek turning at 90 deg angles.

They could be made wider and deeper but then when to stop? It is not feasible to make them big enough to handle rare rainfall, and we only get tropical cyclone type rain typically at 10+ year frequencies (last like this was in the 90’s, and in the 80’s before that – usually it misses us).

There will always be overland flow paths and flood plains. Hopefully these are not built on but where they are, council should ensure floors have a sufficient safety factor above conceivable flood level. Some of the new developments clearly aren’t.

A lot of the flooding was caused by lack of maintenance on existing drains – e.g. sucker trucks cleaning out the drain gates in the airport area post flooding. Consider how much flooding is often observable around the roads with just normal rain.

Sorry but aren’t you saying some quite contradictory things there? At the start you say “Hey, we can’t design things big enough” and then at the end it’s like “If we’d just cleaned our drains more often…”

Also, if you believe that these will *stay* 10 year events, I have an insurance company here that doesn’t believe you. They were the first “serious” companies who started incorporating climate change into their business calculations, because it literally would kill their companies otherwise (without re-insurance to bigger companies above the local market, it would have killed a lot of them already).

The first chart in here is quite interesting: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/sustainable-future/aucklands-historic-flooding-explained-in-five-charts

It appears that heavy rain events have actually been less likely recently compared to the 70’s and 80’s. I am not a climate change denier by any means, but that one event is no proof that there are more of them to come.

Ummm, read the article to the finish? It seems to say clearly to me that what has changed is the INTENSITY. Yes, there were peak rains before. And in that chart, if you only look at the 3-4 biggest events, then the biggest ones “skipped” a decade or two, and the next big ones were a few decades in the past. But they were also a lot less intense. A lot. So even if the overall number of “big rain” events stayed the same (hard to say that from that chart) the greater temperatures (proven, and on track to rise more) will mean every time one of these rare events happens, it will be likely to be more vicious than it would have used to be.

Hobsonville Point being mostly OK is not a surprise, given it has ocean on 3 sides, and is a good amount of metres higher than that ocean. I don’t see how you could make that place flood even if you try.

I was more impressed by Stonefields being OK given that it is literally in a hole in the ground.

I believe the new development in Mt Roskill South survived well too with Freeland Reserve not reaching capacity (from what I have seen).

Roeland – if we just change a place name in your statement, so it reads:

“Auckland Airport being mostly OK is not a surprise, given it has ocean on 3 sides, and is a good amount of metres higher than that ocean. I don’t see how you could make that place flood even if you try.”

Question is, why did AKL flood and not Hobsonville?

A lot if good points in there until it got sidetracked with the whole mana whenua stuff. Maori don’t have some special intellectual or mystical hold over water (be it stormwater or the whole 3-5 waters). They had zero water infrastructure pre-Europeans and haven’t built it themselves since either. Water doesn’t care what race you are, and while it has been European descendants that have built our cities (and inadvertently also caused these related issues), they are no different to issues all around the world no matter what race or country.

You only need to look at the Pacific Islands (where Maori migrated from) to see that their 3 waters often don’t even exist let alone come up to the standards here. Yet somehow we are led to believe that mana whenua would do better than almost anyone else in the world… what a F joke.

Good posts thanks.

It’s not very realistic to think a problem can be solved by simply pouring scorn on other perspectives. Maori have rights over water by law and by simple logic, and the idea that people in the pacific islands don’t have ways of providing sustainable water supply, keeping wastewater separate, and dealing with drainage is disproved by the simple fact they are still there.

Still there? Simple existence sure, propped up by significant aid funding from NZ and Australia as well as large levels of remittance from family – here.

‘They had zero water infrastructure…’ is something you could say about the majority of residents in British cities up to the close of the industrial revolution.

The Romans did better in their 300 year tour of the area.

I don’t believe it is a coincidence that the industrial cities like Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham also lacked democratic representation in Parliament.

Mana whenua are long overdue a hand on the tiller.

So please explain the Pacific Islands (where Maori migrated from)…

Maori receive representation in exactly the same proportion as everyone else does. It’s called democracy – look it up.