The next phase of Waka Kotahi’s Innnovating Streets for People programme was released quietly last week. Now called Streets for People, this is the second iteration of the project, which ran as a pilot from mid 2020-mid 2021. The possibility of a second round of funding seemed a bit up in the air when the 2020-21 pilot programme wrapped at the end of June, so it’s great to sea that Waka Kotahi are re-booting it, with what looks like an improved structure.

In case you missed Innovating Streets for People in the news this year, the first formal round of the programme was launched in the midst of that first Covid lockdown, in April 2020 (also a quiet launch, according to this post we published at the time – although paradoxically, it grabbed international headlines for being first out of the blocks as a Covid response.)

The initiative was conceived as a way to help local Councils to deliver tactical trial projects in their towns and cities that would create ‘a healthier future by putting people and place at the heart of streets.’ Projects needed to involve community in a co-design process, demonstrate a ‘pathway to permanence’, and include before-and-after monitoring and evaluation.

Given the timing, Innovating Streets became Aotearoa’s version of the rapid tactical street interventions seen around the world to make urban environments safer and more welcoming during the Covid-19 pandemic. As we’ve seen, since that first burst of creative response, many of those overseas interventions have led to dramatic, systems-level changes to cityscapes.

Looking back at that April 2020 post, we were excited to see tactical urbanism getting some serious focus from Waka Kotahi. The programme brief had a great list of some really specific kinds of projects it would be looking for, such as intersection safety improvements, pop-up cycle lanes, play streets, and low traffic neighbourhoods.

In July 2020, we wrote about the results of the first round of funding awarded:

A $13.95 million government investment will see around 40 projects that make streets more people-friendly being delivered across the country before June 2021.

In that first round, Auckland only landed $1.4m of the allocated funds for just four projects. A number of other Auckland projects that applied weren’t successful, and there’s a memo shared in the post from Waka Kotahi’s ISfP programme leader Kathryn King to Auckland Council explaining why.

Auckland fared better in the second round, which we wrote about in this post from September last year, successfully received support for 13 individual projects. At times, it seemed like Auckland had a rockier ride than other places, with, for example the Arthur-Grey low-traffic area in Onehunga and the Henderson Town Centre project succumbing to vitriolic social-media-fuelled opposition that drowned out quieter voices of support.

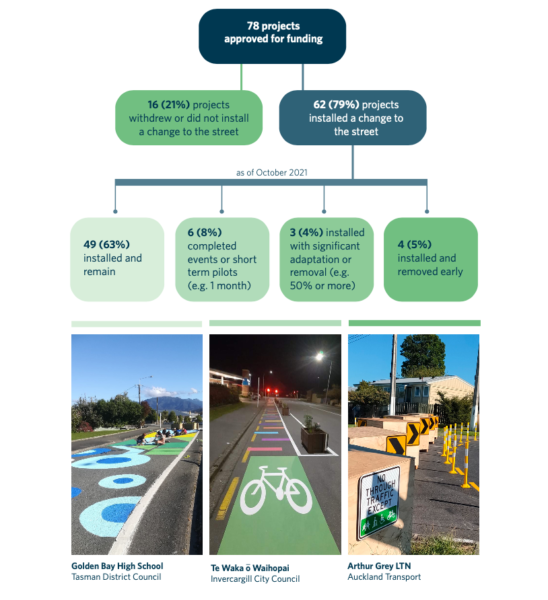

Meanwhile, as the evaluation summary reports, dozens of projects that trialled safer streets for people carried on, with much more constructive results, and the majority of Innovating Streets projects installed across the country remain in place.

One major success in Auckland was Project Wave (the temporary cycleway connecting Nelson Street to Quay Street), which managed to overcome some early opposition and obstacles, and will now be made permanent.

And we’ve heard about some exciting success stories in smaller towns and cities. ‘Create The Vibe’ in Thames, a street pedestrianisation and parklet space, has proved a hit with the community and a boon for adjacent businesses, as well as becoming an art-filled attraction. The lovely Drews Ave project in Whanganui is incredibly photogenic, and has contributed to Whanganui being named a ‘City of Design‘ for 2021 (is Whanganui the new coolest little town in Aotearoa?).

Other projects received less publicity, but still proved valuable in demonstrating that it is possible to quickly encourage more kids to bike to school, to slow traffic on busy streets, and to give people safe places to cross roads. If you’re interested in reading more about the results of the 2020-21 programme, Waka Kotahi’s evaluation can be downloaded here.

For many Councils, their consultants and communities – and I’m sure, for the Waka Kotahi ISfP team – 2020-2021’s Innovating Streets projects were a steep, exciting, frustrating, at times heartbreaking, and hopefully rewarding learning curve.

So here we are, planning to do it all over again. It’s fantastic that Waka Kotahi has come through with a new round of funding. So many lessons have been learned in the last 18 months by the hundreds of people working on these tactical projects around the country; now we’ll get to apply them at scale.

So what does the new Streets for People programme look like?

Vision

The core vision at the heart of Streets for People is still there. It’s about the health and safety of people and communities, and about reducing our emissions by helping people to get about their neighbourhood without a car.

Imagine Aotearoa streets where children can bike, walk or scoot to school independently. Where communities have more welcoming spaces to safely come together to celebrate and share experiences and where you can hear bird song instead of car engines.

Streets for People has been set up to help make that a reality.

A new name

The ‘Innovating’ has been dropped from the heading, presumably as the innovation phase moves towards bedding in tactical techniques as ‘business as usual’: the programme is now called Streets for People.

Where Innovating Streets allowed us to work with councils to trial, test and evaluate these innovations, these learnings are now ready to support and encourage towns and cities to deliver rapid network changes using this evidence-based approach.

Funding

$30million from the NLTP has been allocated for Streets for People, only a negligible increase on the $29m allocated to the 2020-21 programme. The key detail remains the level of support for successful projects: as with the 2020-21 programme, Waka Kotahi can fund up to 90% of each project’s cost. This is a powerful leverage for smaller councils in particular.

Time

This time round, there’s a bit more time to get things right: Councils and communities will have until June 2024 to develop and implement their projects, more than double the length of the first version.

The funding is available over the NLTP 2021–2024 period for towns and cities ready to accelerate their long-term vision by using successful evidence-driven techniques. The programme runs until June 2024, a timeframe that allows for lasting change, transformational work, and strong partnerships with Waka Kotahi and the community.

This seems like a good change, as in the pilot round some ISfP projects simply weren’t able to get off the ground within the tight timeframe and had to forfeit their funding (only $22m of the planned budget was spent.) A longer time period could also allow for more complex and impactful projects to be undertaken.

Process

That longer duration also means that more time can be spent on making sure projects are set up to succeed. The funding will be structured across three phases. They are:

- Expression of interest

- Phase 1 – Funding the Foundations (pre-implementation)

- Phase 2 – Funding the Projects (implementation)

Councils or community groups applying for funding have to satisfy the requirements of each step in turn, to move forward through the process. The purpose of this phased approach appears to be to ensure that Councils really do have the skills, willingness and capacity to see a project through to completion:

The expression of interest establishes whether a council is ready and has the processes in place that will enable them to implement this alternative approach, as well as the willingness to undertake this different way of engaging with their community.

Learning and upskilling of councils and communities is a core part of this phased process, and it’s good to see that support will be provided for councils that aren’t successful in receiving funding but want to build capability for the future.

Expectations

Something we picked up on, both on the project’s webpage and the FAQ sheet, is this strong statement of expectation directed at councils:

We are looking for a strong sense of direction and strategic alignment with Road to Zero strategy and the proposed Emissions Reduction Plan.

So, what can we expect to see?

Honestly, it’s hard to predict what we might see in this round of applications. Applications for funding opened on November 30th, and need to be in by 22 February 2022, which isn’t very much time with the Christmas break in the middle. Hopefully there are some motivated councils and communities ready to go.

Maybe some of the towns that have run successful placemaking projects will expand on their mahi by trialling walking and cycling network improvements. More safe streets around schools seem like an easy win. Perhaps the Ponsonby Streets for People project, which didn’t get much further than a Social Pinpoint page, will be revived. We could even see another attempt at a Low Traffic Neighbourhood. And how about some Covid-safe ‘streateries’?

No matter what, if a few more communities get to learn how quickly, easily, and collaboratively their streets can be made safer, happier and healthier, we can count that as a win.

What would you like to see trialled in your neighbourhood?

Images in this post come from the Streets for People evaluation document.

Processing...

Processing...

I’d like to see a trial of taking a lane on Dominion road on the weekend and turning it into a bidirectional bike lane. The humble desire to ride down Dominion road is latent, it would be great to unlock it.

Or if they want people to drive their cars slower they could implement road speeds in line with the ITF and then do this? I understand this is but chicken and an egg situation, but where these things are, some drivers do just ignore these measures because they are allowed to drive the limit.

Vinegar, spot on about speed limit. Drivers (I am as guilty as others) often drive to the speed limit, so to make streets safer for people we really need to (1) lower speed limit in all local streets, not just a small percentage proposed by AT (2) change the way streets are designed.

I came across this youtube video recently presented better street/road design is paramount for all user experience.

Yea. The first step needs to be dropping the limits, then figuring out where the issues are. This also had serious implications for any safety infrastructure they are building right now. Maybe some of it is not needed or it could be different?

No just bikes is great. Makes me wish I lived in Europe, but amazing thankful I am not in North America.

So a area well known for killing off most disabled people and in the UK well known for denying basic medical care during covid so deaths were frequent and people were left in their own waste. Yep story checks out ableists cannot wait to get over there to see the destruction of human rights and basic access in action.

Great video!

In my area (Onehunga):

1. Traffic calming down the Selwyn St hill (people fly down (and up) it, right outside the primary school) and Arthur St intersection where there are crashes almost every other week.

2. Royal Oak roundabout made more ped and cycle friendly (the current works aren’t doing much to address that).

3. Streateries outside the fish and chip shop and Japanese place on Manukau Rd right by the roundabout. The cars parked here block a driver’s view of peds waiting to cross at the crossing.

4. Onehunga mall made more ped friendly.

5. Cycleway down the length of Church St and/or Mt Smart Rd through Station Rd to provide an east west route.

6. Cycleway down the length of Onehunga Mall to provide a north south route.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with Onehunga Mall. It is one of the few old school shooting areas thriving and if you can’t negotiate it as a pedestrian, do not leave your bedroom.

As for bike lanes down it’s length, what the hell? It’s not a playground, it’s a commercial retail district. Demanding bike lanes everywhere in zones like this undermines realistic ideas. Ironically i walked out on to the crossing on Sunday up from Arthur St and was near missed by cyclists who couldn’t care less about my rights on a crossing.

(shopping areas)

Bikes aren’t a ‘playground’, they’re a fantastic opportunity to massively increase the number of people that can travel to, and park on a constrained retail street like that.

If it were easy to bike in that area, then all the new apartment dwellers would have no reason to drive across the city to a mall, instead biking and shopping locally. Way more convenient, higher capacity, faster, cheaper. Right now Onehunga mall is totally saturated with cars, they couldn’t bring in and accomodate any more shoppers if they wanted to.

Regardless, I think pretty much everyone would agree that adding a few more pedestrian crossings around those roundabouts would be great. They’re actually pretty annoying to cross. People outside of cars are the ones doing the shopping, should make the environment more comfortable for them and encourage them to stay and spend longer.

I’d like see more creative traffic calming that isn’t judder bars or steep speed tables. These basically damage small hatchbacks while hugely oversized SUVs and Utes can glide over them without much inconvenience. I’ve always found the planted gardens in One Tree Hill to be a good alternative.

The AT go to of “raised pedestrian platform” also suck for busses, that need to go about 5 kph to cross them. But yea they do nothing for utes.

Can you send a streetview link of where you mean? I have generally found that narrowings are really problematic for people on bikes, and only do limited things for cars, but maybe I am not thinking of the same location you are thinking of?

The SUV and bus aspect of raised tables is a problem, but the stats still bear out that raised tables are some of the best features for improving road safety at crossings. Swedish table designs in turn go some way towards mitigating the bus issue (the design of AT’s Swedish tables was designed to reduce passenger discomfort as much as possible while retaining traffic calming effect). As for SUVs, I’d like to ban them anyway, sigh.

Not sure if this link will work, but I think they mean this one – and a few others in the area… Outside 2 Kawau Road One Tree Hill.

Good for traffic calming. There are also a few with gardens on both sides that narrow the street to one lane. Greenwood Road in Penrose for example.

https://www.google.com/maps/@-36.9033439,174.7954378,3a,75y,210.64h,82.14t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sVUibdGdmBW2vtr2TA48a3w!2e0!7i16384!8i8192!5m1!1e4

“A longer time period could also allow for more complex and impactful projects to be undertaken.”

I fear that if this statement were true and carried out, the simple and tactical nature of the program would be lost, where lots of change could occur in a range of places, seeded by a central government program.

I agree the transition to more complex projects needs to occur and is noted that there is inequity in the funding allocation and delivery capacity, particularly in AT. This is where the groundswell of positive impact from projects emboldens the expectation for change in our communities.

Not mentioned in the post is the framework for sharing of learnings at the local level, has someone tried a change and documented (most likely plans and a video talking through the project) what they learned, so that it can be a resource for others thinking of similar projects, without consuming time that could be spent implementing the next idea.

“I fear that if this statement were true and carried out, the simple and tactical nature of the program would be lost, where lots of change could occur in a range of places, seeded by a central government program.”

As long as “the programme runs till 2024” doesn’t mean “we will dispense the funding by 2024”, I don’t so much see that issue? A logical way might be to provide multiple tranches of money, with the later ones explictly more targeted at more complex ones? So simple ones can still go faster.

A full cluster of low traffic neighbourhoods – say, 5 or 6 (and the advice is not to implement one, but a whole cluster) – doesn’t need to be experimental in concept but works with this approach because each particular element in the cluster can be experimental. Yet I would class that as complex and impactful. More complex than a simple pair of kerb buildouts at an intersection, for example.

In terms of the timeframe, we know that projects need to be in place for a year at least for the public to be properly informed by the trial.

Don’t forget that Streets for People is to provide 90% funding to allow community-led projects. There’s plenty of other opportunities that should be picked up for standard split-funding for AT and other Councils to take on as BAU. If only WK would make approval of funding for those easier….

Posts are reminding us that Streets for People is only one of a lot of tools for making change – they’re all needed, and they should all pull in the same direction.

And speed humps… the worst idea except for all the other ways of reducing speed. Try to find street space for the better alternatives. Filtered access is always better, if it can be fitted to the messy netwrok that we have to improve.

I’d love to see Eden Terrace, Symonds street, Newton Rd become less of traffic sewer and be far more pedestrian friendly. Walking up Newton I honestly feel like someone’s gonna jump the curb at eventually, not a day goes by without seeing excessive speed and people texting and driving.

Yep, no need for that crap near the city centre. If you want to drive there, expect delays.

At first glance,it would seem that small towns, cities have had better results than large cities. The challenge here in Auckland, is that a whole section,maybe 10 blocks ,needs to be done,(Onehunga,looking at you),to get the proper affect.

Given that these projects need to be lead/proposed by the residents,difficult to see a general consensus across a wide cross section of the community. I fear Auckland will be unable to benefit from these trials. At best, a local school, or group of schools, may be able to engender some interest.

The provinces , are lapping up this central money,to good affect, some really good gains,Thames,Whanganui, great results.

Not necessarily. It requires a council or authority to make a decision and stick to it, no matter the backlash.

This is also what happened in Groningen (the Netherlands) when they decided to split the city into 4 quarters, requiring cars to exit their quarter and use the ring-road to enter another quarter. Meanwhile, free movement between quarters was possible for public transport, cyclists and pedestrians (as well as delivery trucks).

If memory serves, they gave the city a year’s notice on the plans, and then implemented it. The backlash during the year and just after implementation was fierce, with the same arguments trotted out as what happens here: businesses would lose clientele, people wouldn’t change mode, etc. etc.

In the end businesses thrived because there was more (slow) traffic that would stop and shop. The city became a calmer place, allowing for more active modes to take over the space. Even car traffic became faster, as there were less cars on the road.

All you need is a decision making entity to have a good (researched) idea and stick to their guns, no matter the backlash from vocal minorities. But I suspect there is too much a fear of upsetting part of the population, the car lobby and who-knows-what, that drastic overhauls like that will not happen in New Zealand.

+1

There are examples of successful pedestrian streets dating back to the 1970’s, and yet this just keeps repeating.

A major barrier in Auckland I think is the sheer marginalisation of riding bicycles. How else are you going to do those short “15-minute city” kind of trips? They’re often too far to walk, and public transport is way too slow for those trips. So driving it is. European cities tend to be dense enough to do a lot of trips on foot, and often they already have a significant bicycle mode share.

I wonder if this offers an opportunity for Auckland to trial, maybe just on weekend or though I’d like to see it as 24/7, the conversion of one one on the AHB to a bike lane.

Streets for non disabled people you mean. These projects have been notorious for removing basic access and creating increased harm, injuries and dangers for people with disabilities. They instead have been removing often the only form of access available to communities for many and this has severe health and wellbeing consequences. You might have a choice but bear a thought to those who are the MOST marginalised and ostracised in our country. Think before you cut off someones life, remove their access completely and permanently harm them. Every person harmed has hundreds of others behind them who also lose out as the loss of income, community, culture, medical access and family causes a deep wound in the fabric of whanau. Suggesting that creating inaccessible (in the original and true definition) places with what the streets for people has been doing can only be a positive suggests a deep ignorance of basic human rights and design principles. Even a ignorance of basic logistics as well. You cannot put up literal barriers and destroy safe communication on streets without a large price and unfortunately it is the poorest in the community who pay and often lose their lives to your largess. Better to keep the access there is now then to remove it and flush cash down the sewers to the consultants.

I’m interested, what projects or implementations are affecting safe street usage by disabled people? I don’t doubt the importance of addressing this, I’m just not sure what exactly you are referring to.

I am referring to the streets for people projects which have all, every single one, created harms, barriers, loss of access and injuries. Better to not do streets for people projects and keep the access we have now then to further harm NZs most marginalized and vulnerable communities.

When used in this context, “disabled people” aren’t people, it is some abstract reason why we can’t have nice things. It is a rhetorical device similar to “think of the children”.

What seems to be a fight to the end prices for la fitness

that’s all that is clear. We don’t know why. We don’t know what they’re fighting for. All we know is that they will fight and fight again.