Earlier this year, the Climate Change Commission (CCC) released their advice to the government on how to meet our domestic emissions targets. There was some really good stuff in there though we thought it wasn’t quite ambitious enough, especially around the need for mode-shift.

We also had the Ministry of Transport’s ‘green paper’, a discussion document which presented the ministry’s view on how to meet the emissions targets set by the CCC. Most notably, they didn’t agree with the CCC on the level of uptake of electric vehicles that would occur – which meant reducing, avoiding, and/or mode-shifting travel as needed to make a much larger contribution. They suggested that we would need around a 40% reduction in the kilometres that light vehicles travel by 2035, and an over 55% reduction in VKT by 2050.

Today the government has released its first Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) for consultation.

The Government is inviting New Zealanders to inform the country’s first Emissions Reduction Plan with the release of a consultation document containing a range of policy ideas to decrease the country’s emissions, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Climate Change Minister James Shaw announced today.

The Emissions Reduction Plan will set the direction for climate action through to 2035. It will set out action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions across a range of areas, including energy, transport, waste, agriculture, construction and financial services.

“We are putting forward for discussion a range of ideas that that would reduce our emissions and can also create jobs and new opportunities for Kiwi businesses and our economy,” Jacinda Ardern said.

As you might expect, I’ve focused my attention on the topics we discuss the most, mainly transport and housing.

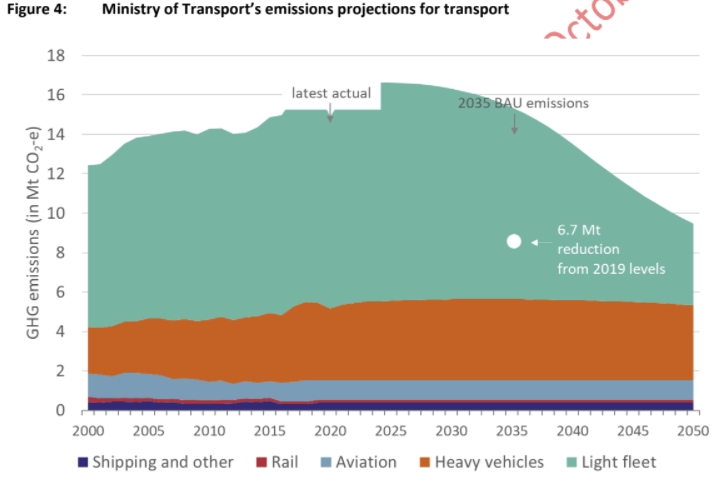

Looking through the ERP, it is unsurprising to see it has a lot of similarities to the work previously completed by the CCC and MoT. They have taken on the CCC’s recommendation to reduce emissions from transport by 41% by 2035 compared to 2019 levels. This is equivalent to a 6.7 mega-tonne (Mt) reduction, and represents a significant difference to our current path as shown below. However, this target is currently being challenged in court by the Lawyers for Climate Action.

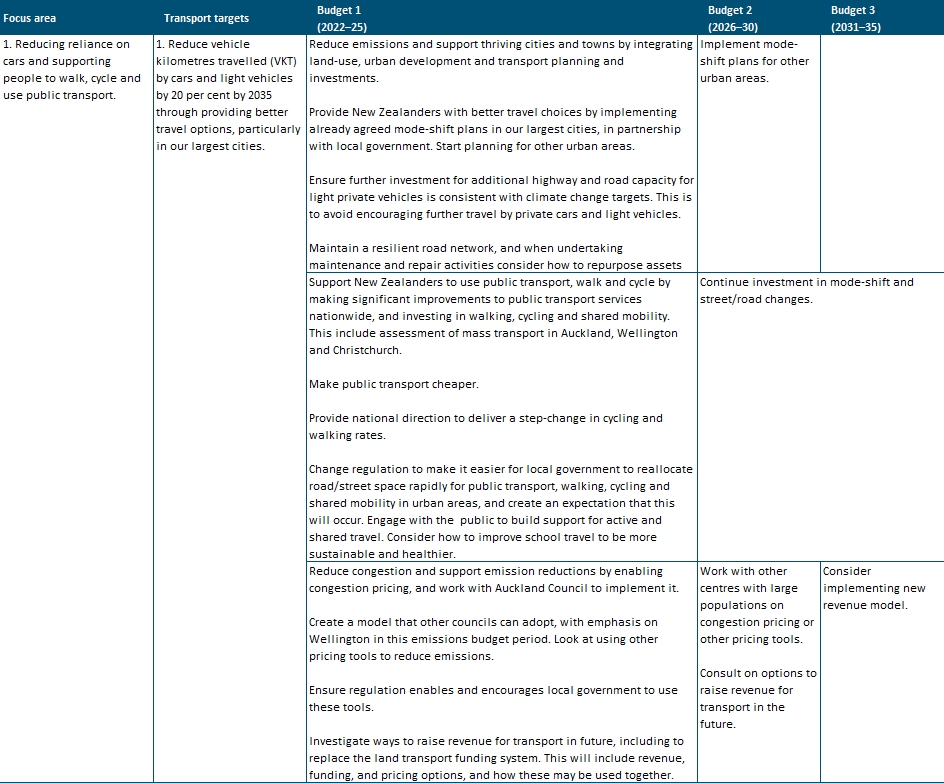

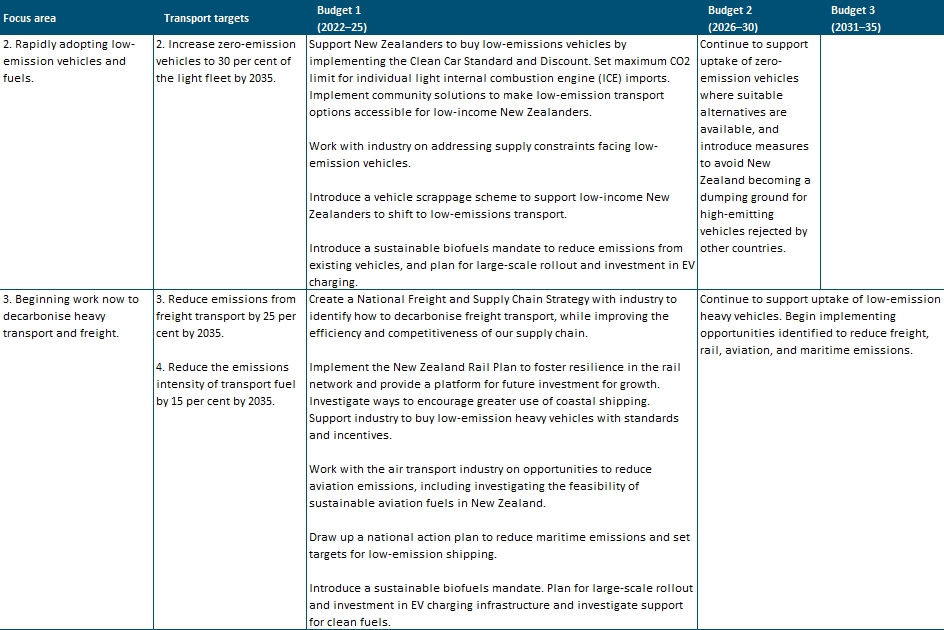

To achieve its stated target, the government have set four transport targets:

Four transport targets

- Reduce vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT) by cars and light vehicles by 20 per cent by 2035 through providing better travel options, particularly in our largest cities.

- Increase zero-emissions vehicles to 30 per cent of the light fleet by 2035.

- Reduce emissions from freight transport by 25 per cent by 2035.

- Reduce the emissions intensity of transport fuel by 15 per cent by 2035.

The first two of those are the aspect of the ERP I was most interested to look at, to see where the government landed, as this was an area where the CCC and MoT differed significantly.

The CCC estimated that by 2035, around 36% of our light vehicle fleet would be electric (down from the estimates in their draft of about 44%). The MoT weren’t so optimistic, suggesting it would be less than 20%. As you can see above, the government have come in between these two figures, with a target of 30% by 2035.

The number of EVs in the fleet impacts how much we need to reduce travel by. In short, the fewer EVs we have, the more we need to achieve emissions reductions by other methods like reduced travel or shifting it to other less emitting modes. The MoT suggested that based on their estimates, we’d need about a 40% reduction in light Vehicle Kilometres Travelled (VKT) by 2035. The CCC didn’t give a 2035 figure, but said it could be just 9% by 2030. As with the EV levels, the government have gone for a figure between these, proposing a 20% reduction in VKT.

Taking a broader view of this number crunching, it’s clear that a robust figure for VKT reduction is required, because the number of EV’s that New Zealand is able to import depends heavily on international factors that our government has less influence over. Planning more ambitiously, to achieve the MoT figure of 40% VKT reduction, would create a system far more resilient to EV supply problems. It would also require the sector to really overhaul its systems and processes – like the outdated business case approach – and this would be helpful in many ways.

The ERP’s 20% VKT reduction reduction sounds like quite a lot to people in the sector, but we’re seeing a much larger reduction right now, albeit a temporary pandemic-induced one. Vehicles in NZ travel just under 48 billion kms every year, so a 20% reduction would see that drop to about 39 billion km. The last time VKT was at that level was about 2004 – when there were nearly a million fewer people living in NZ. That was also about the time we really started ramping up highway spending. I wonder what VKT would be today if instead we had poured all that effort into alternatives?

The impact of the VKT reduction target is likely to be much larger in our biggest cities. That’s because those are the places where alternatives to driving will be the most viable and so will have to do most of the heavy lifting to achieve that target.

As a quick exercise, let’s assume the focus is on the big cities, and therefore rural areas and smaller towns achieved just a 5% decrease on their current VKT. That would mean VKT in our six biggest cities would need to reduce by about 60% in order to achieve the national target.Imagine Auckland with 60% fewer cars on the roads.

There are of course a lot of opportunities in small towns too, especially with cycling networks. In which case, a 10% reduction in the rest of the country would require about a 46% reduction in the cities.

To achieve that level of change is going to require a significant improvement in alternatives. Below is an overview of how they say this VKT target will be achieved.

As with both the CCC and MoT reports, there’s a lot more detail in the ERP about these topics and some great language around it. Like everything, though, we’ll have to believe these changes when we actually see them.

One of the first things we’re likely to see in the coming few years will be mode-shift plans. Auckland already has one, but it has been completely ignored by all agencies involved.

The new and revised plans will set mode-shift targets for each urban area and prioritise:

- urban development in areas with frequent public transport routes

- using transport demand management approaches, alongside changes to the way we plan and manage urban form

- reallocating significant amounts of road/street space to rapidly deliver more dedicated bus lanes and safe separated bike/scooter lanes

- completing connected cycle networks

- more traffic-calming and low-traffic neighbourhoods

- improving footpaths/crossings for pedestrians.

Here is the overview of the proposed actions for the other three targets:

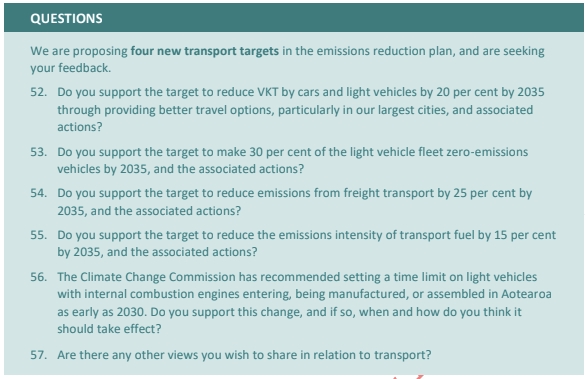

And finally for transport, these are the questions they’re asking for feedback on.

Planning

Outside of transport, there is also a section on planning. The part from it that stood out to me is below.

Integrating emissions into urban planning and funding

We do not know the total emissions contribution of urban areas. We need to develop a way to measure the emissions associated with urban development decisions. This should incorporate the likely lifetime emissions of transport and energy use that would be enabled under different scenarios, and embodied emissions in buildings and infrastructure.

Understanding the emissions impact could inform strategic, spatial and local planning and investment decisions, and drive emissions reductions going forward.

There are major opportunities in planning and investing for a more compact mixed-use urban form, oriented around public and active transport. As noted in the Transport section, the Government will require transport emissions impact assessments for urban developments and factor these into planning decisions (with requirements to avoid, minimise and mitigate transport emissions impacts). Transport plans and future investments will also strongly prioritise travel by public transport, walking, and cycling.

Future work could explore the:

- economic benefits and distributional impacts of intensifying development in towns and cities

- price signals and economic instruments to support this.

This includes options proposed by the Resource Management Review Panel, such as ‘value capture’ tools, as well encouraging the uptake of alternative, low-carbon infrastructure and its financing.

That “future work” part seems somewhat redundant. There is already a heap of work on these kinds of things internationally – so this sounds like someone trying to reinvent the wheel than using what is already available. Unfortunately, the tendency to “do another study” rather than tackle our problem of sprawl is contributing to our transport, infrastructure and biodiversity problems.

Overall, there are some really good things in the ERP – but the challenge will be seeing it actually implemented.

I worry there isn’t enough ambition in the plan, nor resilience to change; especially if it’s weakened following consultation, or various agencies undermine it by just ignoring it as they have with other plans. Perhaps one thing that is needed is some trigger points that will modify it. For example, if after a few years the EV uptake and VKT reduction are not at the levels expected, this should trigger a requirement for additional measures to be delivered.

There is also a lot of discussion in the climate space right now. How will the government change the plan if it becomes clear that much higher international emissions cuts are going to be required? How will they change the plan if emissions aren’t reducing as required?

Finally, it would be useful to take a leaf out of the UK’s great cycling and walking plan. One of the measures in that is that local authority performance on delivering walking and cycling changes can influence how much overall funding they get.

The consultation is open till 24 November.

Processing...

Processing...

Reduce vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT) by cars and light vehicles by 20 per cent by 2035

Well surely they cant expect to build massive new motorways and at the same time expect people to drive less. This might finally be the nail in the coffin for these motorway projects. Please WK.

Overall this is great news though. Setting a clear expectation that people will have to drive less (even if 20% might not be the desirable amount) is a very clear line in the sand.

Expectation and desirability do not necessarily equal reality though.

It’s going to be a hard sell for the Government especially with the way they’ve had to sell Covid restrictions, and what they are going to have to sell to get buy in for Three Waters

It shouldn’t be a hard sell with the public. There is plenty to like. The problem will be with the mouthpieces of the political economy of car dependence in the Old Media.

So a broad approach is required, involving good communications about the whole picture and deliberative democracy, rather than letting each project in turn be nuked by talk back.

Unfortunately, the gummint seems to know best and continues on its merry way.

The discussion document has:

“require transport emissions impact assessments for urban developments and factor these into planning decisions, with requirements to avoid, minimise and mitigate transport emissions impacts ”

also,

“Require further roadway expansion and new highways to be consistent with

climate change targets.

Hīkina te Kohupara noted that central and local government will need to review investment in urban highways and road expansion. These projects could induce more private vehicle travel. Submissions on Hīkina te Kohupara supported this view and suggested that projects should only be funded if they help to reduce transport emissions.

For this reason, we will ensure further investments that expand roads and highways are consistent with climate change targets, and avoid inducing further travel by private motorised vehicles. “

Anybody got a link to the full report. The Enviromint website seems not to have been updated yet?

Here

https://consult.environment.govt.nz/climate/emissions-reduction-plan/

Thanks Muchly

https://environment.govt.nz/what-government-is-doing/areas-of-work/climate-change/emissions-budgets-and-the-emissions-reduction-plan/#consultation-on-the-emissions-reduction-plan

On Bio fuels I would like to see what is envisaged. What is the raw materials, how will they be transported to a central processing point then how they will be processed and distributed too the users. This is the third report that mentions them if you count this report plus the CCC and the MOT. For Pete’s sake this report writing has got to stop at some point a case has to be made with sufficient detail to either proceed or reject biofuels as an option for emission reduction. I suppose they just keep it as an option just in case some one is willing to have a go at it or if there is some kind of technological breakthrough which would enable it. I hope they are not thinking of importing biofuels.

The CCC already upped their biofuel scenario to 5% of all liquid fuels by 2035 (including domestic aviation). Now the ERP says 15% emissions reduction from biofuel. Biofuels don’t eliminate emissions entirely, so this might require 20-25% biofuel. The discussion document from a few months ago was all about food-to-fuel – but at least it focussed on lifecycle emissions which is a step forwards.

A lot has to happen here but at first glance, by going with only 20% reduction in VKT, they had to up the biofuels to make the numbers add up.

The population may be 15% larger by 2035 so the VKT reduction per person has to be more like 30%.

Reducing VKT by 20% means removing 1 in 5 vehicles.

“particularly in our largest cities” suggests that a larger portion of vehicles would be removed in cities, say 1 in 4 or 1 in 3.

I can’t see any of the above happening just by “providing better travel options”. How much better could alternate options get any time soon, and who will pay?

I’d see motorway congestion charging with significant charges as the only viable way of achieving this objective.

10 years is a long time if they work at things consistently. Considering how far Auckland has come in the last 10 years (excluding covid), we didn’t even have the EMU’s for example.

There are also some massive projects coming online in a couple years. And with more money and motivation, even more could be coming and maybe an expansion in scope of projects. Maybe the eastern busway could be further extended for example.

Of course there will also be congestion charging.

Its all achievable I think.

The big cities are expected to reduce their VKT’s but Rural areas and towns don’t have to. Hardly seems like a fair split. Many councils have buses running in rural areas just need more customers. Same as in town.

Great to see some targets. However, so frustrating that questions 52 to 55 are double bangers. Do you support the target AND do you support the actions? So a double yes is supportive feedback. A double negative is obviously unsupportive. What about a yes/no or a no/yes.

I would love to say I reject the targets are too low though I do like the actions proposed and would like also to see …. Does that classify my response as positive or negative? A researcher with an agenda could class it either way.

I just wish feedback requestors would treat us like children and ask one question at a time.

+1

I am a advocate for electric vehicles I would love a tesla model 3 but I am concerned that these EVs with their massive battery packs and big price tags will be a problem.

With city’s designed for cars It will be hard to get people out of them,

My solution would be to allow micro cars like the ones often seen in China and similar to Japanese kai cars to be imported and used on motorways and reduce the speed on most urban motorways to 80kmph to make it safer for these cars.

These cars are similar in size to a gulf cart and have much smaller batteries so will be affordable for most, the down side will obviously be safety, so preventing the mix between these cars and trucks will be a must.

Otherwise we need to start building Metro lines like China.

I agree with you, John. I think microcars can be part of the solution, too.

Chinese EVs (BYD, Nio, Xpeng, Ora, MG) and Telsa are closing in on parity for equivilent ICE vehicles, what you will see in the EV market is exactly what happened to the likes of Nokia and Kodak..nobody in 2 years time will contemplate buying a petrol car for the same price as an EV where the running costs both for fuel and servicing are significantly higher, along with the technology some of the new EVs have (autonomous is literally around the corner). So we won’t even need incentives..coupled with better battery recylcing, using old battery for solar storage etc EVs will become the norm.

Agrere with smaller models, the 2nd best selling EV in China is a tiny car classed as a quadricycle. We need to allow them and to provide a better driving environment.

Are quadricycle class vehicles like the Citroen Ami even legal in NZ?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Citro%C3%ABn_Ami_(electric)

Joe, simply not true. Look at the huge taxes on ICE vehicles in Norway and yet only somewhere between 60 and 70% of people are buying EVs.

‘Joe, simply not true. Look at the huge taxes on ICE vehicles in Norway and yet only somewhere between 60 and 70% of people are buying EVs.’

I said in the next 2 years..so come back in 2 years and tell me it wasn’t true. Cheers

taka-ite, your stats are out of date: in September, more than 91% of new cars in Norway were EVs (BEV + PHEV). I understand some of the incentives are now being rolled back, as they’re no longer needed.

The comparable figure for NZ was for the first time over 10% at least.. but there’s a long way to go

What are people’s thoughts about releasing a discussion document rather than the actual plan (for consultation) or the actual plan (for immediate implementation)? Is it to build public support? Is it to delay action to the next term or after a change in government? Surely Labour will not be in power continuously until the 2030s, when the biggest cuts need to start under this plan (sorry, discussion document).

Even with a surprise cut (or transfer to Singapore) of 600,000 tCO2 a year from closing the Marsden Point oil refinery, we will miss the 2022-2025 budget by a significant amount with no apparent suggestion in the document how to close it. And as Lawyers 4 Climate Action NZ have pointed out, the budgets themselves do not meet the Zero Carbon Bill or the Paris Agreement.

Some suggestions:

• Double petrol prices. It has an immediate effect on VKT and petrol prices. Generates more income.

• Subsidize Public Transport. Immediate large uptake in PT. Spends that extra income, massive cuts in Emissions.

• Ban importation of all new and second-hand ICE vehicles. Just do it. Make NZ EV only.

• Require all new houses to adopt rooftop PV panels. It’ll help charge those EVs.

• Create an E-bike industry here, so we don’t buy everything from Taiwan/China.

• Ditto E-Bus.

• Require all long-distance freight to go via Rail or Sea. We know that works, even if the truckers will complain.

• Stop the importation of coal, full stop. If we run out of electricity, then so be it. We need to stop thinking it is an endless source. Its not – we need to Manage our use.

You can’t just make radical un-mandated changes like that without having alternatives in place. It would damage the economy, increase inequality/poverty and see the implementing government turfed out (which is why no government would dare do such a thing in the first place).

Personally I can’t see any major changes being made. At the end of the day governments do things by reading the electoral tea leaves.

Let’s not forget the history here: car dependence has grown through politicians making radical un-mandated changes that ruined the alternatives that were in place.

And unfortunately looking at tea leaves is about all that seems to be happening sometimes but it’s important to realise that even polls aren’t the most democratic way forward, let alone the listening to talkback reckons that seems to be all that’s going on before political decisions are made (I’m actually looking into this atm).

The assumptions behind most people’s reckons about what the public want and would vote for are often the opposite to reality. In the UK, for example, would the tabloids or tv commentators have generally given the impression that these results are typically what the public want?:

https://twitter.com/giulio_mattioli/status/1447855631751340041?s=21

I love the fact there is a traffic reduction target. That is a first for New Zealand and something I first advocated in 1989 or 90. The challenge with be getting mode switch targets and investment plans aligned to this overall target. Delivering a 20% reduction in VKT requires huge changes – I have joked before that the choice is not whether you have heavy rail or light rail but how you pay for both.

In particular it will require a focus on Auckland as a whole, which means lifting the gaze from the isthmus, especially in terms of urbanisation. As I have commented on earlier posts – emissions reduction through increased density needs to be integrated with great urban design and affordable housing initiatives across the city.

Arguing over two versus six storeys in middle-class areas close to the main CBD is largely irrelevant to emissions reduction. What is really needed is thoughtful retrofits across the post-1960 landscape, retrofits which support increased localisation to enable greater access to services, goods and experiences without using a car.

This will take careful planning and partnerships, not a deregulate and hope approach ala the NPS-UD. It will also need to be driven in part through community-planning, not resentment inducing top-down decisions.

My biggest fear is that neoliberalism has become so embedded in planning discussions, on this blog and in government, that our emissions future will be shaped by an ideological haze rather than the solid international evidence we need to use as a touchstone. The end result will be higher emissions and greater inequality and another missed opportunity. I want to be wrong 🙂

And the “pre-1960 landscape”?

Ah well that’s different you see, because that would bring up arguing over two versus six storeys in middle-class areas close to the main CBD.

Which is about developing where people want to live. So it’s about equity and access and walkable lifestyles.

But apparently is largely irrelevant to emissions reduction.

Inner Auckland is relatively densely populated and has a low emission profile. This due to the fact it was mostly constructed prior to widespread car dependence. The priority for this area ought to be increasing affordable housing through quality public developments on underutilised or “brownfields” sites that are not currently used for housing. The deregulatory approach is more about displacing low-income renters with higher income apartment dwellers, with only a modest net gain in population. This is probably close to emissions neutral at best due to the embodied emissions in new construction and the emissions from waste created by demolishing wooden buildings. There is almost no impact on transport emissions.

Most of Auckland existing transport emissions come from the areas developed in the last 70 years. Reducing these emissions is central to achieving reduced VKT and reduced emissions.

Sprawl has already happened, and if we want an evidence-based approach to emissions reduction then it is in the areas of high-car dependence that we need to start creating more choices for people in those areas. The global evidence is that the greatest gains in emissions reductions from transport and land-use integration come from moderate increases in density in low-density areas.

So, our priority ought to be creating a network of liveable walkable urban villages, linked to sub-regional centres and a strong core with excellent cycling and public transport facilities. This needs planning, partnership and community engagement not deregulation.

Mother of two – are you suggesting central Auckland is the only place “people” do or could want to live?

We know from census data it is the only place where a significant amount of people gets to work not in a car.

https://observablehq.com/@roelandschoukens/mode-share-map?mode=walk&sa=1&who=work

It is also not “relatively densely populated”, a large part of South Auckland is more densely populated.

Because it is the central area in a city of over a million people you would expect it to be more densely populated than more outlying areas. It isn’t, on average there is little difference in density 4 km away from the town hall vs. 15 km away.

When you say we know it is the only place where most people don’t use a car, I take it you are agreeing with me? ie that this is a low emissions area, and intensifying here will have little impact on existing emissions.

And to make sure I am not misunderstanding you, when you say it is not relatively dense, you mean against what you hold as a theoretical ideal based on a unipolar city? Because it is certainly denser that the vast bulk of post-1960s sprawl.

Auckland is not a unipolar city and hasn’t been for at least thirty years. We need to work with that. A network of urban villages linked to sub-regional centres and a strong core is the low-emissions pathway. Do you disagree with that?

I agree parts of South Auckland are denser, and that is a great strength on which to build, yet they have higher car dependence, and their needs get little attention – why?

The low emissions from inner areas is exactly why most growth needs to be focused in these places, so that population growth does not immediately become emissions growth.

We also need to transform outer areas to become less car dependent, but adding more people im already car dependent places usually results in more car dependency and more emissions.

Trev – that argument has some merit if all we are concerned about is slowing growth in emissions. But we need to talk reductions. This means looking at new and existing emissions together. This perspective teaches us quite a different lesson.

The vast bulk of transport greenhouse gas emissions come from existing post-1960s landscapes. Creating localised intensification, coupled with great transport choices, in these areas means that existing as well as new residents have lower emissions.

Even if your new residents have slightly higher emissions that might be the case if they moved close to the CBD, this effect is far outweighed by lower emissions from existing residents who can meet more needs locally without a car. Existing residents vastly outnumber new arrivals, and it is the existing emissions that need to fall, as well as slowing the growth of new emissions.

So an emissions-reduction led intensification strategy would focus now on integrated transport and land use projects to retrofit the high emission areas and increase localisation. This, rather than emphasising growth adjacent to the CBD, is the priority from an emission reduction perspective. Otherwise we end up with a wealthy, walkable core and everyone else condemned to the rising costs of car dependence in a climate constrained world.

A very practical sign that more people want to live in these areas are the high land prices.

Also the area has more restrictive zoning than the areas further out (single house zoning + heritage overlay). That doesn’t make sense.

The question is what will be easier: increasing the density of the inner suburbs where people can already walk to things, or retrofitting those further out suburbs to be less car dependent.

I would say having better “urban villages” is quite desirable, not only for emissions but just for having actual communities. However we kneecap ourselves in a similar way: we insist on having *only shops* in some predetermined blocks and *only residential* in all the rest. But the best place for apartments is above those shops.

Roeland – what exactly do “high land prices” show? Well, first up they are generally a derived value – people buy property, which is a combination of land area, development and location.

Second, and this is important, there is no “market for land” – rather property is traded in a sequential parcel by parcel system. In any given period only a very small proportion of total properties is bought and sold.

The land value for an area is generally an extrapolation from sales of a small number of properties, Largely these are sold by auction and the value in an auction is determined by the maximum willingness to pay of the second highest bidder.

So what we know when we see a high property price is that at least two people with a high degree of disposal income and/or securitisable wealth both want to live there. Think about the amounts paid for exclusive retreats for example.

The extent to which these high prices are a useful reflection of where the average person wants to live depends on the extent of broader income and wealth inequality. In New Zealand this is significant, and so a high price for a villa in Ponsonby tells you little about where people in general want to live.

I am not saying some people don’t want to live there, just that “land” or property prices are driven as much by broader inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth as anything else. By itself, a high property price, or even a series of high property prices, is a sign of the fact that wealth desires that property, that is all.

Meanwhile…BAU4WK: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/rotorua-daily-post/news/scrapped-auckland-harbour-bridge-cycleway-could-fund-regional-roads/CINIASBZQ35JERL6IIXUXMRYZI/

I think this take on the announcement sums up my thoughts nicely:

“The government is proposing increasing the emissions budget recommended by the Climate Change Commission for the 2022-25 period by 2 megatonnes carbon dioxide equivalents, followed by cuts of 5Mt CO2e for the 2026-30 period, and 11 Mt CO2e in the 2031 – 31 period.” (sourced from Carbonnews.co.nz).

Soo.. business as usual for now, but we’ll start cutting emissions soon. Reminds me of all the vehicle/emissions target graphs from the MoT, the reductions seem to always be forecast for the next period. Repeat ad nauseam.

“The government is proposing increasing the emissions budget recommended by the Climate Change Commission for the 2022-25 period by 2 megatonnes carbon dioxide equivalents”

Greta +100

PM FAILS TO SCORE

Is there any talk of removing the fringe benefit tax on firms who provide employees with public transport passes? I’ve been told in the past that this is the reason why this isn’t done very much in NZ.

Best job perk I ever had was the zone 1 to 6 Oyster card

for myself and my spouse when working at Transport for London. Why drive when you can get free PT.

“Why drive when you can get free PT?”

But it is more complex than that. Kids get free public transport on the weekend, but huge numbers are dropped off to sport and other places. PT becomes more attractive when then is a stick, or two. In London those sticks are the congestion charge and the lack of availability/price of parking.

In Auckland AT seem to believe they have a responsibility to provide low cost parking for everyone – everyone apart from the rate payer.

Clearly lots of interest and ideas on this site, but no way of reaching a consensus. As Heidi says, we need to start using deliberative mini-publics to spend time learning and deliberating towards agreed effective actions. Otherwise this enthusiasm will all be lost in the usual “have your say” charade. No mention by James Shaw on the radio this lunchtime of enhanced ways of involving the public in developing policy. Depressing really. But on the bright side, the recent trial of the mini-public approach in four workshops run by the Complex Conversations Project of Auckland Uni together with Watercare showed how keen the public are when given the opportunity to participate fully.

James Shaw always strikes me as just a little bit less than who we need fronting this.

I know he is not in Cabinet, but he just seems like the guy who stumbled on the Climate Change political opportunity earlier than others, was therefore first in line to get the keys to drive it, but doesn’t really know how to get out of 2nd gear…

I think that is a little harsh on James. There much that I might disagree with James about but this seems unfair. I can personally vouch for the fact that he has been passionately aware of climate change issues for thirty years and that he is in politics to deal with climate change.

Politics is the art of the possible. James has got us a cross-party agreement on a Zero Carbon Act and is trying to produce an emissions reduction plan that isn’t a political football. I absolutely agree the science tells us we need to do more, but we also need to avoid lurching uncertainty that will delay transformational changes in business.

On methane for example, the reality of accelerating climate change, international pressure and demands for better performance from our international customers will drive the political acceptability of more radical cuts. Picking too big a fight two years ago would have meant that Groundswell was twice the size, and research within agriculture was less far forward.

I have been aware of climate change since the mid-80s. I worked on the Government’s first ever reduction plan. I am so painfully aware that we need to do more faster, but getting too far ahead of public opinion can set us back more than we gain. To use a real world example, we got Roads of National Significance and PTOM partly as a response to Labour and the Greens pushing hard on public transport, walking and cycling funding and reduced car dependence.

Pretty soft target.

Why not start now not in a 10 years time?

A big thing the government can do to reduce VKT is to ramp up the roll out of fibre. There are large rural/semi-rural areas adjacent to our cities that often have very slow internet connections. These make it almost impossible for people to work from home.

The target is 87% of the population by the end of 2022. It really should be 90% by the end of 2022 and increasing by 1% each year thereafter to 95%. After 95% it does become a bit too tricky and expensive to go further.

The allowance per property should also be increased for tricky installations (eg rural properties are often further back from the road than urban ones so require more cable).

The day that farmers agree to pay any form of carbon tax, be it on their animals or their utes is the day that we might consider subsidising their broadband.

1) fuel already includes buying carbon credits. So there is already a ‘carbon tax’ no?

2) there is I think a fairly important debate around c02e calculations to be had in NZ, and that short lived biogenic methane is not 40x as bad as carbon dug out of the ground. Agreeing to GWP100 was a bit of a poor move for NZ IMO. Pretend that co2 does no warming after 100 years, and averaging all the warming over 100 years? Of course short lived gasses are going to be hard done by. It’s practically a subsidy to buy a little time of oil companies to keep on digging, at the expense of removing any sustainable steady state methane emissions.

In my opinion there is no real reason that fiber needs to be extended into rural areas. There just needs to be a better market and coverage for wireless data. On the 3G powered wifi at my mums home we can have 4 people streaming hd video no problems at all. At lower population densities it performs fine.

Meanwhile we are buying new Diesel Locomotives to replace the fifty year old South Island fleet. But it’s probably too early for battery or hydrogen fuel cells alternatives and they are claiming greater efficiency and less Nitrous oxides. If battery locomotives become a thing maybe they can be multi unit upped with a diesel to capture regenerative braking energy, provide more grunt and fuel savings.

https://www.kiwirail.co.nz/media/new-locomotives-to-replace-south-island-fleet/

https://www.greencarcongress.com/2021/05/20210518-wabtech.html

Anyway we can’t have 50 year old locomotives running around just as we can’t have 70 year old planes for our air force. At some stage they have to be replaced.

I’m sure a lot of bureaucrats have worked hard on this but it’s still a pile of poo. NZ is a filthy country and there’s no getting around it. Whether agricultural or tourist (at least international flights are gone for now), poor public transport or the miserly price for grid tied solar power. We are in cloud cuckoo land if you think much of this bureaucratic nonsense will do any good. There’s just not enough time. If there was an additive in petrol to show emissions, we might be shocked at what we are doing to our planet, but hands would still go up to say, what can I do? Yes, I can cycle, walk, drive an EV but EVs still put out arguably 65% of the lifetime of petrol emissions so any reduction target less than at least 35% in 2021 will still see the world go up in flames and sooner than you might think.

The only pragmatic way to save the planet in the time we have left is to further offset with carbon credits. In addition to reducing journeys and changing modes. The current EV rebate scheme is shameful. It’s just awful politics. Instead, the government should encourage personal responsibility and legislate carbon credit offset payments to be tax deductible. It would loosely cost say $350 million, based on 3.5M taxpayers ($300 personal expense at for arguments sake 30% average tax = $100 tax reduction). So, if you choose a moderate monthly amount of $25 which offsets about 12 tonnes of carbon annually, your normal transport emissions will be offset this year, not in 2030. Your soul will feel better, and the planet will feel better from the 500 or so trees planted at sites around the world. It will cost you $200 a year plus, but it might, just might buy a future for the next generation. Anything less is mostly hot air.

1) The VKT reduction wont occur without a) road users paying substantially more of their true costs & b) much freer land use rules, even less restrictive than the proposed RMA changes.

2) The approach is still not holistic as we don’t have a national population strategy – the amount of growth has a significant impact on emissions. Ideally we would be aiming for a population growth rate where the net wellbeing/capita change is maximised (where wellbeing = economic+social+environmental). This is likely to be less than the very high pop growth rate in 2019.

3) A nationwide vision zero/net zero carbon surface transport infrastructure standard to provide for and fully protect vulnerable road users.

apols – im feeling a little cynical at the mo.

Auckland Harbour active transport crossing – cancelled – unpopular (unwanted)

Covid Level 4 in Auckland – not popular – cancelled

Climate Change Action – lets see how this goes

No chance of a reduction in VKT while there is no infrastructure provided for active modes. E.g. there are no north-south cycle lanes on the isthmus and no plans for any.

No chance of a reduction in VKT while AT makes PT less attractive. E.g. annual fare increases well over the rate of inflation.