The quiet streets of Level 4 are here again. City-dwellers are waking up to birdsong and falling asleep to rare silence. People who need to drive for essential reasons are enjoying magically congestion-free journeys. And in our neighbourhoods, we’re once again seeing the everyday world through different eyes.

While Covid is a looming cloud nobody wished for, quieter streets are a lockdown silver lining: a low-key stress-relief element that most people have had free and direct access to, during an undeniably stressful time. They’re also a rare glimpse of a low-traffic way of life, reminding us how much traffic usually fills our thoughts, our ears, our public space.

As Holly Walker put it in The Shared Path, her November 2020 report for the Helen Clark Foundation:

“It is important not to romanticise the lockdown experience… Yet the lived experience of quieter streets during lockdown has led some people to ask: now that we have experienced low-traffic streets and neighbourhoods, and found that we like them, what can we do to keep them, without the need for lockdown conditions?”

What’s different about Level 4 streets?

It’s striking how quickly adaptable we are. Level 4 finds people instinctively reallocating street space (and parking lots) for local exercise and fresh air. I wondered if there might be a bit more driving this time, as more of us head out for vaccinations and Covid tests. But I did a Backyard Bike Count on Sunday, and just as in April 2020, fully 2/3 of local traffic was people on foot or on wheels, vs. 33% vehicles. How is it where you are?

One surprising thing is that despite last year’s lessons learned report about fighting Covid via street space reallocation, and the report into the link between transport and mental health, there didn’t seem to be any ready-to-go plans to create safe street space in an equitable way. Not even lower speeds, which would help take pressure off our health and emergency services by reducing the risk of crashes. (Our government is great at articulating why and how we can keep each other safe, especially the most vulnerable; so this is a puzzling blind spot.)

Lockdown brings its own stresses, no doubt about that; but it also removes others. Sometimes you don’t notice a particular stress until it vanishes. Biking along my local main road in Level 4 (a 50khm arterial, usually busy, and wide enough to land an aircraft on) I realise I’m missing the usual dread of being knocked into passing traffic by someone carelessly opening the door of a parked car.

Likewise, there are possibilities you don’t see until they’re suddenly happening:

- people crossing the road at their own pace, rather than scurrying apologetically or being tugged along

- joggers, dog-walkers and passersby borrowing street space for more courteous overtaking

- skateboarders, roller-skaters, families on bikes, leaving the footpath and choosing the street

- people in mobility scooters enjoying uninterrupted journeys, with cars not parked or idling on the footpath

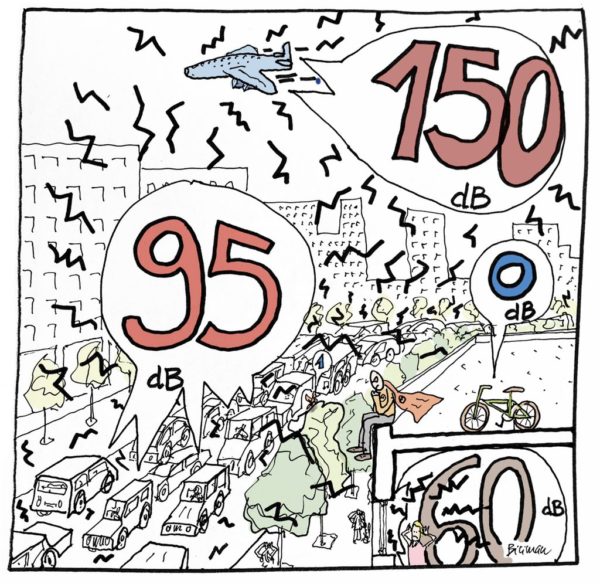

One of the most striking changes is heard, rather than seen. A single car approaching at the usual speed suddenly sounds like a plane coming in for a landing. How do we ordinarily cope with this level of noise? When did we decide it was “normal” for neighbourhoods?

Cities aren’t loud; cars are loud. (Level 4 traffic conditions make the contrast even clearer than usual.) pic.twitter.com/GhMjJJ4nMw

— Jolisa Gracewood (@nzdodo) September 5, 2021

You can hear birds and human voices from a distance. (The hush also registers on underground seismometers, and life becomes more peaceful underwater, with dolphins audible from a whole kilometre further away than usual).

To quote a small child on a bike I heard in the early days of Level 4, approaching from half a block away: “Mummy, it is MUCH more quieter out here this day!”

Time to bookmark these feelings

With or without any extra safety measures in place, our quiet streets give us a real-time simulation of what low-traffic cities feel like, and how they work a little better for everyone…

- If you’ve driven anywhere in Auckland in the last couple of weeks, you’ll have felt the relief of congestion-free travel that comes from reducing car trips to the essentials. (Fun fact: the Dutch are regularly ranked as the happiest drivers in the world – because everyone who doesn’t need to drive, isn’t driving).

- If you’ve caught the bus, you’ll have noticed how easily the routes run on time when there’s less traffic on the road. With congestion out of the way, every lane can be a bus lane.

- If you’ve been for a walk, roll, or bike ride in your neighbourhood to keep your spirits up, you’ll have felt the confidence and connection (albeit distanced for now) that low-traffic streets offer to young and old.

- If you’ve sent kids out for some solo fresh air without even thinking of warning them to be careful of cars – or noticed there are way fewer “sneaky driveways” than usual, you’ll have spotted the way low-traffic streets empower children.

- If you’ve walked to the shops to get your steps in, or worked from home, or made arrangements to have something delivered, or batched up a few errands to save on car trips, or even noticed you have an extra hour in the day because you don’t have to deliver kids to or from school – you’ll have clocked how possible it is to trim a little driving, and thus a little stress, out of your day.

- If you’re just sitting quietly at home listening to the birds, you’ll know how the natural world floods back into our senses when traffic drops. (Also, while nobody officially keeps track of how many pets are lost to traffic each year, I’m willing to bet it’s a lot less at the moment – and we know how important those little critters are to our quality of life.)

Make note of these feelings and insights, and all the small wins you notice in this quiet time, because they’re going to come in really handy over the next few years.

Opportunities ahead

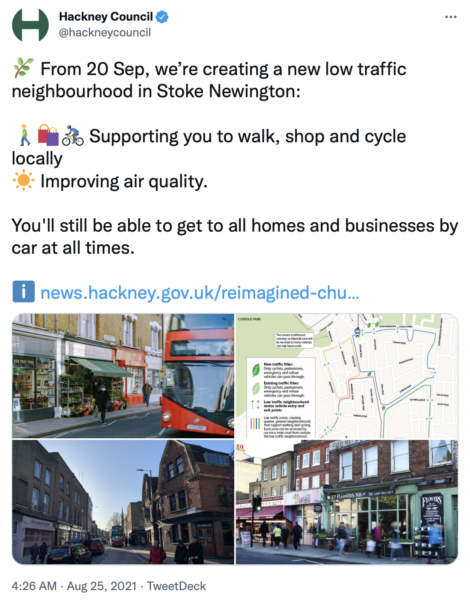

In Aotearoa so far, our quiet streets have largely been temporary, evaporating like a dream as soon as life returns to “normal”. But cities around the world are leaning into the opportunities. In the UK, each week seems to bring an announcement of a new ‘low-traffic neighbourhood’ or pedestrianised shopping street somewhere.

So far, the research suggests they’re achieving results (safer streets, cleaner air, equitable outcomes), and public feedback (including election results!) suggests that on the whole, these changes are welcome. Not so much “build back better” as “there’s no going back!”

More than ever, we need breathing room in our cities, for our physical and mental health. And in the teeth of extreme-weather events we also need to feel confident we’re doing something to tackle the other great stress-factor of our times: climate change.

The future weighs most heavily on children. So any way we can give young people a better life right now has got to be a good thing.

A quick refresher on LTNs

The basics of a low-traffic neighbourhood are, well, pretty basic. Every house and shop within the LTN can still be reached by car or emergency vehicle – but through-traffic is channeled along arterial routes. and side streets are strategically ‘filtered’ to deter rat-running.

With short-cuts out of the equation, using a car for a local trip might take a few minutes longer – but the trade-off is quieter streets all round. Take away through-traffic, and streets become more attractive to walk, bike, scoot or roll, for local trips like school, shops, the bus stop… or purely for fresh air and pleasure, like in lockdown.

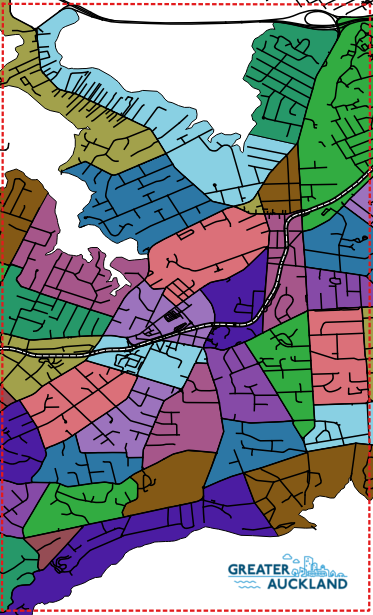

This, in turn, reduces traffic in the wider area, even on the main roads, as people’s travel choices shift over time. For more immediate equity and effectiveness, LTNs are best delivered in batches, and linked together with a citywide circulation plan for good, frequent public transport. They also go well with decongestion-charging.

In the last year, Aotearoa’s been giving LTNs a go, under the Innovating Streets For People programme. While some demonstration projects have been prematurely and unfortunately nipped in the bud, others have quietly blossomed into exemplars of the way ahead.

Low-traffic neighbourhoods aren’t new in New Zealand

We’ve had low-traffic neighbourhoods across the motu for quite some time; we just don’t tend to call them that. You may know them as:

- Cul-de-sacs, which make excellent locations for street parties and play streets, as well as traditional places to learn to bike, skate, or play pick-up ball games.

An Auckland play street in progress (Image: Healthy Families Waitakere)

- Historic traffic calming features, now a cherished feature of many ‘leafy burbs.’

- Gated subdivisions designed to keep out through-traffic, including shutting the gates overnight, and retirement villages whose smooth 10km/h walkable streets are great for residents and visiting grandchildren alike.

- Old-school neighbourhoods that butt up against hard edges: motorways, railway lines, golf courses, creeks, parks – because there’s no through access, there’s no through-traffic, and streets become common space.

- The laneways and courtyards and mews of the central city and Wynyard Quarter.

Tiramarama Way in Wynyard Quarter (Image: Heart of the City) - Housing complexes built around walking paths and common greenspace.

- New developments, where a key part of the sales pitch is the ability for kids to ride and scoot safely.

- Holiday parks and campgrounds and beach towns. Even if you get there by car, you gladly ditch it for the greater pleasures of daily barefoot walks, or a bike to the dairy on the rusty beach bike.

I've come to the conclusion that the sign of a thriving NZ beach town is a little collection of bicycles by every cafe, shop & path to the beach. pic.twitter.com/Ntv4VNqNrT

— Kathryn King (@KingCyclesAkl) January 21, 2018

- And the correlative: Auckland over the summer holidays, when streets fall strangely silent, and going for a bike ride feels like time-travelling back to the 1980s when there were half as many cars on the road.

New Zealanders, as much as anyone, get the value of a “village” vibe. Heck, some people pay a premium for it!

Joining the dots

As the impacts of climate change swirl around us, so many of today’s worries are going to look very different in the rear-view mirror. One thing we do know is that the road ahead will necessarily involve a lot less ferrying ourselves and others around in cars, across the board.

This opens up a lot of avenues for less stress and more resource in our daily lives. More ways in which we can flourish and add a little extra time to our day.

What I’m getting at is: we never needed a pandemic to taste the possibilities of a life less trafficky, or to see the room we have to manoeuvre.

But we’re here now (again). This time, are we ready to test ways we can hold onto the good bits?

Our councils, ministers, and transport agencies hold responsibility for reshaping public spaces for better. It’s now a race against time, with climate change-driven weather events already reshaping them for the worse.

The bit we’re in charge of is how we feel about proactive change: how we adapt, and how we help others find their own reasons to join in. This is why it helps to pay attention to how we feel about quieter streets, and how we discuss them with our friends and neighbours.

Change is challenging, for sure. But what if it also felt like a window opening, like a holiday, like a childhood memory, like a treat? Can we see ourselves in that story?

A Low-Traffic Neighbourhood by any other name would smell as sweet

We could call it… a place where people work from home when they can, so others can come and go more easily. A place where essential workers and caregivers and deliverers and people who have no choice but to drive don’t have to battle with inessential traffic to get where they’re going.

A place rich in low-carbon transport options, whether it’s all-day buses and trains connecting you to the rest of the city, your bike, a rack of scooters on every block, a shared fleet of electric cars.

A place where your groceries or library books or even healthcare might just as easily come to you by cargo bike or electric van, saving you the need to take a car and pay for parking.

A place where most of your everyday needs are no more than fifteen minutes away. A place where local bulletin boards overflow with creative solutions, support for those in greatest need, and bringing the community together to see the big picture.

A place where kids don’t need constant chauffeuring, let alone to and from school. A place where a child wouldn’t think twice about biking to meet a friend, or walking to the shop to fetch a ‘last-minute’ item while you get on with the dinner.

A place where heading out without the car is a perfectly reasonable choice that adds life to your day, and maybe even days to your life.

So I think it’s okay to find some solace in our current quiet streets – a glimmer of active hope, even. They remind us there is a less stressful world for the taking, outside the front gate. The quiet streets of lockdown aren’t normal. But they could be.

You don’t have to time-travel, or fly to Europe, or wait for the holidays (or wish you could afford one), or buy your way into a fancy neighbourhood. We can start right where we are.

Processing...

Processing...

A great post to remind us what we need to be aiming for! Love the Paris picture.

… what we need to be demanding.

Sadly all this will change when alert levels drop,mask use will be mandated,(can l use that word) at all levels . Public transport, busses and trains are perfect “vehicles” for the delta variant ,no opening windows and very rudimentary air conditioning,and use will plummet,we will become a car to carpark commuter society. The congestion will be as bad as ever,and there will be absolutely no chance of reallocation any road space away from cars.

Problem with current cul de sac is there is no short cut for pedestrians.

The new planning rules should have pedestrian and cycling short cut in residential network toward bus station, schools and town centres.

The current cue de sac forcing pedestrians to walk long detour should be discouraged in new subdivisions.

Yes, and not just a narrow passage… Needs to be 3m wide.

This is where grid street patterns are excellent rather than the maze designs popular with developers here. You can have culdesacs in conjunction with grids which also work better for PT.

There must be two Auckland’s as we still have plenty of cars out here in the south. Plus the odd walker and biker. I walked around the low traffic neighbourhood planters and paint in Papatoetoe west. Its colourful and I haven’t heard any moaning yet however I am not that socially connected. Maybe it has just calmed the streets and hasn’t impacted that much on travel times on the arterials. The overbridge at St George street has being a choke point for travel for many years no one would notice if they had spent an extra couple of minutes there.

Car ownership in Mangere/Manukau is under 50% which is much lower than the wealthy parts of Auckland. A multi modal transport is about choice and equity. Cars are expensive, both for individuals and for society.

Meanwhile car mode share to work is around 85%, which is higher than most wealthy parts of Auckland.

It sort of shows us that travel to work data shouldn’t dictate the overall shape of the transport network. If most people don’t have a car, yet most commuting is done by car, it probably means that the transport network currently excludes non-drivers from employment.

Maybe you will just exclude more people from employment if you don’t cater for cars.

Would you? Cater? For a car?

Eat them! Eat them! Here they are.

My observations are cars are driving faster, even in the newer narrow street subdivision around Papakura / Takanini. My walks / bike rides with my toddler are still a little on edge when it comes to road crossings.

Yes the overall number of vehicles is way lower, but the speed certainly hasn’t dropped.

The speed last year was recorded as having gone up, and this is an international phenomenon; how to counter the trend is also established. This year, this increase in speed is a result of Government and AT choice to not act upon the evidence for what to do to keep us safe.

Personally, i’ve actually been driving slower during the lockdown. It’s really given me a sense of empathy for cyclists and pedestrians who are a lot more prominent on the roads (since i’ve never really cycled before). It’s made the idea of speed limit reductions on our urban roads feel much more natural. I’m really dreading the return of our noisy, dangerous car gridlock.

Thanks Jolisa, I hope people do start to reflect on the benefits they get from low traffic living. It is pretty obvious the children love time spent out and about with whanau or independently moving around their neighbourhoods, and I hope some of the grown up decision makers reflect on this. We went for our walk on Sunday and decided to use a coin toss to determine which direction to take at each junction -a great time was had by all.

Idea of the week for transporting freight not the virus between regions at different alert levels. Put it on the train. One driver versus 30. One nasal swab versus 30. Save the cotton buds.

Very good.

Friends in Bath are enjoying emergency street closures for easy social distancing. What’s the understanding amongst advocates, Jolisa? Do you understand why we don’t have them, especially with that Lessons Learned report? Have AT said the reasons they’re not following the advice?

I’m getting the feeling Low Traffic Neighbourhoods are being resisted.

It is great waking up without hearing motorway noise. It is like before Transit NZ built it and told everyone it would be fine.

It makes a huge difference. I’m looking forward to reallocating those motorways to rail and cycling. 🙂

Hard to see it happening. You have a better chance of making 85% work from home permanently. Meanwhile the quiet has me thinking about retiring to Kawhia.

Miffy, do you know much about intersection design?

Or anyone else for that matter.

I’m trying to find someone to answer questions I have about some reasons for things.

https://goo.gl/maps/g7eLQa9r1qS1ajzN9

In the linked map, why doesn’t the bus lane extend all the way back to the intersection, with the left turning vehicles from carlton gore road having a larger painted turning circle to keep the bus lane more open.

Same just across the intersection here:

https://goo.gl/maps/YCiC8vqrz8SysmBT8

Traffic there routinely blocks busses crossing the intersection for several cycles, its not improving car flow at all, I cant figure out why they’ve done it. Its really common around the city too.

Also do you know how AT models traffic flow at intersections? What software etc.

Most don’t like the rhythmic lapping of waves due to coastal inundation between their toes, but each to their own.

I didn’t do it but it looks like they have tried to keep two through lanes for general traffic. The capacity of each lane is greentime/cycletime x 1800vehicles per hour (that bit varies but 1800 vph is the same as 2 sec per vehicle ie 3600sec/hr/2.). If the cycle is 100sec and the green is 40 seconds then for each lane you get 40/100 x 1800 = 720. Two full lanes doubles that to 1440. The short approach due to the bus lane ending and the short departure due to the bus lane starting again reduces the capacity of the 2nd lane somewhat but it is better than nothing. It all fails if the downstream queue blocks the whole thing up and nobody can move. The capacity upstream of a bottleneck is the bottleneck capacity and no higher. Sounds like what you are describing. They may not have tested this at all before putting it in. Sometimes they decide they are doing something regardless. They may have used SIDRA which doesn’t do a great job with bottlenecks. Alternately someone used a microsimulation model and spent a fortune, a heap of time and got results nobody could fathom.

Thank you miffy, I didn’t realize it would impact throughput for cars so much.

I think in this specific case its not really adding any capacity to the intersection. The bus lane coming in from the north, its not adding any capacity for straight traffic because its left turn only for everyone except busses. And coming from the south I’ve never seen any car queue up in that left lane for a straight movement. Although I may have a selective memory.

I think AT could be doing a lot with a little in this regard. And some minor reduction capacity for general traffic, perhaps a bit more theoretical capacity, could yield a huge increase in reliability / speed of bus times, especially in these network crumbling scenarios.

Given that the lanes merge, the absolute maximum capacity you’ll get is the downstream capacity of a single lane, i.e. ~2,500 vph. Miffy is spot on in his criticism of SIDRA. If someone has modelled this intersection in isolation, the capacity results will be completely wrong. But a lot of people will blindly believe what comes out of a model.

I have a much more cycnical view on why this looks like this. It’s a rare treat for me to be more cynical than Miffy.

If you use the older bits of streetview, you can see this went in in 2008/9. It was introduced by Auckland City Council, before AT existed. ACC refused to designate bus lanes through intersections across the city. To be fair to them, bus lanes were a very new part of the legislation at that time and ACC may have been worried about the risk of trying to enforce them.

Jack, it’s a design standard for Auckland that all bus lanes end ~50m before an intersection. This makes it easier to indicate to people people to know when they can enter a lane to turn left without getting a ticket.

You rarely get bus lanes that continue through an intersection unless there is a 24/7 bus lane on the departure side (Like Fanshawe) which isn’t the case at this location.

As Miffy suggests, a Sidra model would get better results with two through lanes, even though one is useless in practice. It’s a problem with relying on models too much in design. This is one possible reason, but I don’t know for sure.

Ari

Is it standard that we always allow the left turns into the closest lane, even if that is a bus lane?

When we have multiple turning lanes we certainly allow traffic to turn directly into the right lane.

The question is, why cant we have cars left turn into the right lane here (see link)? is this not allowed?

https://goo.gl/maps/aG8WvRMaDw3MxmA57 (from the perspective of the left turning car)

We could paint the wide turning lines like they do when there are multiple turning traffic lanes. And a “left turn into general lane only” sign or something, instead of the turning traffic give way to pedestrians sign. Or would this be too much confusion / not legal?

I believe this section the cars are turning into now is a 24/7 bus lane. There aren’t any hours signs that I can see. And from the entering side (southbound) the bus lane has limited hours, but there are yellow lines for a long way, and the lane that the busses go straight from, is a left turn only for cars. So it kind of is a 24/7 bus only movement.

Thanks for the info!

A bit alarmed that you cite gated communities as a good example of a walkable community – gated communities by definition not only keep out other people’s cars they also bar other people and present pedestrians with sizeable detours to get around them. Gated communities might be very attractive to those who live in them but are anti-social and anti-community. The same might be said of some large apartment developments that prevent through site links which might otherwise exist.

I think she means the pace and vibe once you’re inside, not the way they connect to the outside world.

“gated communities by definition not only keep out other people’s cars they also bar other people and present pedestrians with sizeable detours to get around them”

This is not true. Gated communities can allow pedestrians through. As a courtesy to the wider community, or as a requirement of the resource consent.

Doesn’t that defeat the whole point of a gated community?

It depends what the point of having a gated community is. Sometimes, the whole point is to exclude other vehicles, not other people.

And then there’s Weiti Bay.

https://weitibay.nz/residents/

https://maps.walkingaccess.govt.nz/Viewer/?map=b1d1e76a6c754d11b3f3fd9dfce1eb12&extent=1751310.1095%2C5940333.7739%2C1756469.6089%2C5943133.2801%2C2193

Weiti Bay is a fantastic example of a place where owners should have been forced to allow pedestrian and cycle access to the waterfront

Public access to the beach is “allowed” but from this document (P 18) it seems like it will be gated too.

https://unitaryplan.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/Images/Auckland%20Unitary%20Plan%20Operative/Chapter%20I%20Precincts/5.%20North/I547%20Weiti%20Precinct.pdf

Gated communities are the ultimate recognition that public space in cities is of negative value and it is an amenity to be insulated from it.

If the point is to exclude vehicles it is simply called a street with a bollard.

The University of Auckland campuses, along with many other universities are great examples of gated communities that prevent non-university vehicle access, but allow pedestrian access on a courtesy basis.

OK but as far as I know nobody calls these examples “gated communities”.

Even though they have gates on their driveways.

This is true re Gated communities. That’s why they have gates. By definition. It seems Auckland is being held ransom to a small group of pushbike fanatics.

If they’re holding the city ransom then they’re not very effective. More motorway going in than cycle lanes

It’s the stuff of snowflakes or privilege (and probably both).

Reduce the car’s dominance from 99% to 98% and suddenly, its oppression…

Selwyn village in Point Chev no longer lets outsiders access the coastal path.

Eh? I walked through there last week.

It was closed for a month for some not-very-needed repairs, but open now. You never could go through Selwyn Village to access it.

(and the walkway belongs to Council anyway and it was Council that closed it for repair. It’s part of Eric Armishaw Reserve)

Anthony is right. We used to live in Humariri St, and we’d walk through to the beach in the early 2000’s but they locked the gate to the top of the steps mid 2000’s. The residents I knew there had liked our young family going through and talking with them, but community access wasn’t valued by management.

@Heidi thanks for the history. I thought he meant recently. I don’t rate Selwyn Village management too high (reasons not relevant here) but having a through way for randoms could be a concern.

Aren’t all Retirement Villages examples of gated communities – and aren’t they good in all aspects? Yes, cars have to drive round them, and yes, many people do walk round them, but they will often be open to pedestrians at two or more entrances. They seem to be low speed, low traffic, safe walking environments for people who are often visually or audibly impaired and physically handicapped by old age. Got to be a benefit and a good example to everybody! Also rather low-crime and low noise, and a big local employer of all the essential workers.

More modal filters at intersections with main roads please – reduces the right turning into them across busy traffic, turning out of them and opens up pocket-park and linear walking options that aren’t there now.

This does highlight an issue with LTN design. Reducing access options using modal filters and controlled turn also requires modernising the main routes that will remain in use for vehicle traffic as well as PT and active mode longer journeys. No Right Turn across busy traffic lanes is best, but needs to be supported by the means of getting where you’re going. Roundabouts solve almost all problems, given good design and not hampering the active modes.

That’s easy enough – it’s not sealing off streets completely. Plus roundabouts tend to consume a lot of space and that’s not likely on sidestreets branching off from main corridors – in reality, not every one of those side streets needs to feed into the main corridor if you can reach them using other streets on other blocks – which opens up the pocket parks – which we could use to better serve things like bus stops on the main thoroughfares.

Great post thanks. Noise pollution is a significant issue in NZ. Yet not well or consistently monitored. 600,000 NZers live with levels of traffic noise pollution that exceed WHO guidelines, ie. is basically creating heart disease. And studies show that even when you habituate to it (and we do), its still causing damage. An important public health issue that we need to do more about. LTNs are a great solution

I have some lockdown stuff to share. I had a walk around Grey Lynn and found some new things:

* There’s a new beautiful block on Surrey Crescent 13 (just across the Grey Lynn school), looks like it’s always been there, great work of integrating higher density into existing town fibre. There’s a nice inner backyard where kids of the block can play together. Ockham’s Newton on the other side of the road looks monstrous in comparison to this.

* There’s a new tactic traffic calming near the Grey Lynn School. Looks really good.

* Two old villas on Rose’s road were demolished. I’m wondering what’s going to be built there.

* It seems like real work on the Okham’s green house on the Williamson avenue has begun just before the lockdown.

* There’s a new lot sale sign on the corner section adjacent to the Countdown on the Vinegar lane.

* Just before the lockdown I took a train to wellington. This was a great experience. I think track condition is good enough for sleeping in sleeper train.

* Apparently the train isn’t considered to be a transport. When the lockdown was proclaimed the return train was cancelled late in the night before the departure date. We’re almost stuck in Wellington, but succeeded to buy flight tickets back to Auckland.

* Sudden flight allowed us to try new orange AirportLink bus and new Puhinui station. Last time I tried public transport from the Airport was in 2014 and it was complete disaster. This time everything worked smoothly. We just used our hop cards, the journey on the AirLink, Train and InnerLink was charged as a single transaction with quite a competitive price. Connections are quite convenient. Sharing a short video of this transit:

https://youtu.be/_eKClLhtR7U

+1 Thanks, interesting. Good video.

Were you given a refund for the return train or a chance to ride again? The Government and Kiwirail haven’t treated regional rail seriously for decades.

Yes, the full amount less card charges was refunded.

I was thinking maybe they consider trains some tourist frivolity. But then again, as a tourist you’re equally screwed.

Andrew, that block you’re talking about on Surrey Crescent is probably Cohaus – http://cohaus.nz/

I agree, it fits the street beautifully!

Dreamed up by a collaboration of architects, planners, urbanists and their friends. Part of the reason it’s so great is that they don’t provide any car parking for private cars; just a double-stacked park for 6 shared EVs. And lots of bike parking, of course.

Yes, that’s the one. A quote from the website: “On site, we will provide at least 30 cycle and 10 car parks. At least two of the car parks will be for shared cars which will be owned collectively by the Cohaus community.”

“But we’re here now (again). This time, are we ready to test ways we can hold onto the good bits?”

Unfortunately I suspect not. Indeed, the Devonport Locals facebook page in Auckland recently included a post by a person who reminded pedestrians and cyclists to keep out of the way of motorists. A discussion about the legal responsibilities of motorists and pedestrians ensued. However, there seems to be more support for changes on Tamaki Drive.

Many of the Living Streets projects have been campaigned against by business people who fear the loss of a few carparks will damage their business. Others have been attacked and physically destroyed by locals who are reluctant to switch to more active travel means they see as more time-consuming, who see street art and sometimes giving way to pedestrians as an affront to their values, and consider the Living Streets process to be profoundly undemocratic. I suspect that it is a matter of convincing people that physical exercise is good for them, and there is a need for safe corridors for walking and cycling. And also of increasing urban density so that people with limited private green space of their own support making better use of space currently occupied by roads and carparking, and there are more shopping and cultural services nearby.

“Indeed, the Devonport Locals facebook page in Auckland recently included a post by a person who reminded pedestrians and cyclists to keep out of the way of motorists.”

Ah yes. The arrogance of “my journey matters but yours doesn’t”.

From Our Auckland

“Innovating Streets is about creating safer, more people-friendly places across our region,” Phil Goff says.

“The government funding means we can work with local communities and local boards on the design and delivery of creative projects to improve our streets at a low cost.

“Ideas can be tested and improved in response to feedback from local communities and businesses, and where projects work well and gain strong support, we can investigate making changes permanent.”

So things only change for the better with strong support? And yet it seems that if two or three people complain about the removal of a car park it doesn’t happen?

Can I politely suggest that much of Aucklands’ problems with street improvements might start and end with the person named above.

Meanwhile in Hastings alleys between streets seemed doomed with a councillor and local residents arguing that they are a “haven for violence and drug dealing”.

Hastings councillor Malcolm Dixon, a former longstanding principal of Frimley Primary School, said he fully supported closing the alleyway.

He said that included others like it in the region that are close to schools.

The article is paywalled, but you can read it on Pressreader, where it is on the front page of Hawke’s Bay today.

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/a-hastings-alleyway-was-a-good-idea-30-years-ago-now-its-a-haven-for-drug-dealers/LBKZL6CNGP2ARKDUXHLEZLZHVY/

I wonder if there is a plan to close Pakowhai Road near Frimley School because it is so damn dangerous.