This is a guest post by Hope Puriri. Hope’s whakapapa is Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua Ōrakei, Ngāti Awa and Tūhoe. She is a spatial designer at Matakohe Architecture + Urbanism in Whangārei.

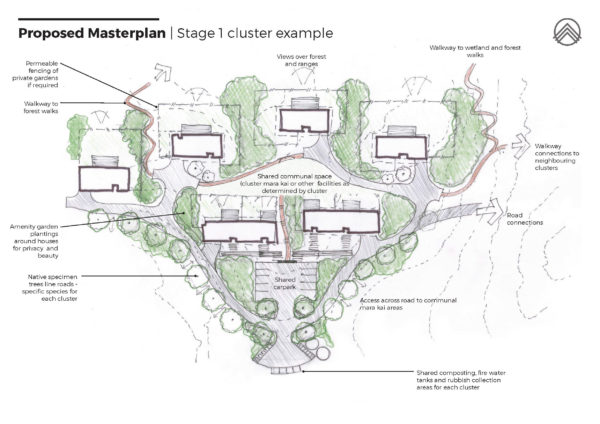

Featured image from Matakohe Architecture + Urbanism.

He aha te hau e wawa rā, e wawa rā?

He tiu, he raki, he tiu, he raki

Nāna i āmai te pūpūtarakihi ki uta

E tīkina atu e au te kōtiu

Koia te pou, te pou whakairo ka tū ki Waitematā

I ōku wairangitanga

E tū nei, e tū nei!

What was the wind that was roaring and rumbling?

It was a wind in the north

A wind that exposed the nautilus shell (symbolising both a sail and the unfolding of a new order)

And in my dreams I saw that I would fetch the ‘wind’ from the north

To support the mana whenua at Waitematā

The lines above are a prophecy by Tītahi, a matakite of Ngāti Whātua, predicting the tides of change to come across the Waitematā isthmus in decades to come. It was with this in mind that Apihai Te Kawau, a tupuna of Ngāti Whātua, invited Captain Hobson to relocate from Kororāreka to Waitematā.

Matakohe Architecture + Urbanism was started by my director and whanaunga, Jade Kake, who has a passion for papakāinga, marae developments, and land use development plans, which she’s published a book about. About 75% of the projects we work on are on whenua Māori (Māori-titled land). One of the good things about being a part of the waka (as I often refer to our business), is being able to bring it back to my whānau: having the space and knowledge to guide our whānau through marae and papakāinga development projects, including some of the regulatory and governance requirements. It’s an absolute delight for myself to do this kind of mahi for whānau Māori, of Te Tai Tokerau in particular.

My role as a Future Director on the Whai Māia Board, which delivers the social, environmental and cultural aspirations for our hapū, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, has me travel on a monthly basis from Whangaarei Terenga Parāoa (Whangarei, as it’s known by the majority of New Zealanders), to the Whai Māia office base in the central area of our papakāinga at Ōrākei.

I am interested in the contrasts that exist between the two places.

While my whānau of Ōrākei are established, structured and on a pathway to ensure our people and community are supported, it is a different landscape here in Te Tai Tokerau.

Kāinga Tuatahi, an innovative 30-home development, is one of the many living papakāinga assets that Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei has. Kāinga Tuarua, the next phase of whānau housing, is in the stages of being planned for. There are also many homes and units on our kāinga that have been established over several decades through various financial support systems.

Among the many things that have helped Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei successfully develop papakāinga, two of the most significant factors are the Te Tiriti o Waitangi Settlements and the close-knit relationships we have with various government departments, organisations, businesses and corporates.

However many of the hapū of Te Tai Tokerau are still awaiting their claims to the Waitangi Tribunal to be honoured and settled upon with the Crown. This includes the iwi in whose rohe I was raised in – Ngāpuhi. While we are awaiting a decision about potential pathways forward and what a settlement could potentially be, Ngāpuhi is unable to move forward with the physical development of a post-settlement world for the iwi and its many hapū.

Ka pū te ruhā, ka hao te rangatahi

We have several papakāinga and marae development projects in our current business kete, all at different stages of development. We are also preparing ourselves for the potential rise in jobs to come our way after the Budget 2021 announcements from the Central Government which included $380 million towards papakāinga developments and repairs across the motū, and ring-fenced $350 million from the Housing Accelerated Fund for papakāinga infrastructure.

That is a big boost not only to the current national housing crisis, but also for my kāinga, Te Tai Tokerau, where we have a lot of people living in substandard living conditions, particularly across the more rural areas. Kaumātua (elderly) and families with three or more generations in them are living in homes that require urgent, if not desperate, repairs, along with cabins that are on blocks. This article from Newshub paints a stark picture of housing in Te Tai Tokerau, where some homes don’t have bathrooms or running water. Like a lot of other places around Aotearoa, in our urban and suburban areas in Tai Tokerau you can find overcrowded properties where the houses are so full that some whānau are living in the garage or shed. I also see many people, families, couples, elderly, teenagers and others, that are living from their vehicles if not on the streets.

He kai kei āku ringa

Through the different papakāinga projects on whenua Māori that we’re working on, we’ve worked with whānau of different sizes to help them achieve their goals towards returning to their ancestral lands. Papakainga are unique legal structures that can be complex for whānau to navigate, and require specialist knowledge to manage. There are too few consultants with this expertise, which is another barrier to successful development on Whenua Māori. However, the body of knowledge and guidance is growing.

Te Puni Kōkiri (The Ministry of Māori Development), Kāinga Ora (formerly Housing New Zealand), Te Kooti Whenua Māori (Māori Land Court) and other organisations offer guidance and support for Māori to develop papakāinga projects on their whenua – land that is Māori title, not general.

One of the harder parts of a papakāinga development project is when the governance structure is not established to function properly and getting a consensus on a decision. Māori land, in particular where multiple shareholders are concerned (which can be up to hundreds or even thousands depending on the size of the block), presents the challenge of being able to bring the shareholders together to move forward on a project or idea that comes to the surface. It can also be challenging to get the right people in roles of governance, with the skills and time to be able to fulfill that role. It can take between 12 months to three years for a papakāinga development project to reach the resource consent stage.

Another element of a successful papakāinga development project is the finance. Te Puni Kōkiri, Kāinga Ora and others can provide up to a certain amount of financial backing, but the whānau also need to make some form of financial contribution in order to progress housing in the project. It is very difficult to get financial support (a home loan/mortgage) from almost any bank in the country to build on Māori land, due, in most cases, to the land having multiple owners. Finance ends up coming from multiple sources. Working up a financial model that incorporates TPK, Kāinga Ora and whānau contributions is an important part of the process of a papakāinga development, to ensure that the development can and will happen.

Technical Feasibility Studies are a good way to see how a papakāinga can be developed into a project or not, something I’d recommend to anyone wanting to see what a papakāinga could look like on their whenua. These involve a organising a team of technical experts to undertake site investigations, and then lead whānau and Trusts through a process of understanding the whenua and what possibilities and opportunities exist.

Nā tō rourou, nā tōku rourou, ka ora ai te iwi

With the boost in funding for papakāinga in this year’s budget release from Central Government, we can expect a rise in Māori wanting utilise their whenua for papakāinga housing. During the feasibility study process, experts will be able to provide advice and guidance on suitable options for the project, including climate conditions, soil and water effects, information which will be incorporated alongside whānau history and matauranga about the whenua. More technical experts and consultants will be called upon to work with Iwi Māori, and this brings opportunities to both train Rangatahi Māori in this work, and up-skill non-Māori kaimahi about tikanga Māori ways of working.

Whangarei District Council has a papakāinga chapter in their District Plan that’s 10 years old now. The chapter supports papakāinga development within the district on all whenua Māori and encourages the owners / shareholders to undertake a Papakāinga Development Plan which is based on the Feasibility Study. If more local governments across the country did something similar within their district plans, in particular the regions with more whānau returning to their whenua, it would help whānau to be able to take up the opportunities available with papakāinga on their whenua.

He aha te hau ka hau mai nei?

What is the wind that will arrive next?

Processing...

Processing...

Excellent post, thanks. I hope you’ll write more posts – there’s so much in this. Keen to know about processes and also would love to see more information about Kainga Tuatahi.

Thanks, Hope! Great post. We have a papakāinga development under construction in Pt Chevalier that has got a great design and will house many families.

I’m interested to know if you have in-house transport specialists to help incorporate sustainable transport design from the outset?

Is there a way, perhaps through Local Government New Zealand, to work on the support that Council RCAs can give to developers of these papakāinga? It may not be appropriate to alienate land by vesting public roads, but an equitable and affordable alternative may be needed for long-term asset management. Advice on design standards appropriate for asset management may be helpful. Private developers are often not doing well for their customers by constructing private Joint Owned Access Lanes in place of equivalent public streets. Papakāinga should not become burdened by asset management costs greater than Council RCAs would normally meet.

Papakāinga may be better set up to agree the way place and movement are to be managed in a way that can be better than conventional public management.

Good post. “It is very difficult to get financial support (a home loan/mortgage) from almost any bank in the country to build on Māori land, due, in most cases, to the land having multiple owners. Finance ends up coming from multiple sources. Working up a financial model that incorporates TPK, Kāinga Ora and whānau contributions is an important part of the process of a papakāinga development, to ensure that the development can and will happen.”

Is this working, from your point of view, or do you think there are other changes that need to happen to make getting a loan easier?

I am certainly not an expert, but from my understanding a lot of the issue is collateral. Normally the asset you leverage against is your land, and if you cant pay then the bank takes it. But Maori land I believe cant be removed from that iwi’s ownership so cant be used as collateral.

I am unsure what the alternative could be. The government could remove these ownership requirements, and that would allow iwi to sell marginal land and put the money somewhere else. Doing with their land as they see fit, rather than the government telling them. But the issue is when it goes south. Eg the investment fails, you might get calls of predatory banks taking advantage of indigenous people etc. The government could become the loan guarantor, but that could lead to some very poor investments becoming made, or being criticized for their choice of loans they back. Seems like opening a can of worms as far as the government is concerned.

Of course this is difficult. Where banks are comfortable with loans secured against the (consensus-imaginary) value of land title, they need a different security to fund iwi investment. It’s up to government and Reserve Bank to build a system in collaboration with the banks to open up the opportunity to the banks to lend capital for these schemes.

Great post. Lots to think about in here.

Thank you for writing this post, I enjoyed reading it. I have been thinking a lot about housing lately and it seems like this is an area should be given a lot more in the Government’s budget. I wish you every success.

Great article & generous sharing of your knowledge