This is a guest post by Camilla Payne. Camilla is an Urban Planning student at the University of Auckland.

In my life, I walk with my feet split between two worlds. One hearing world and one deaf. Sometimes I identify myself as deaf. Sometimes I feel more hard-of-hearing, and as the state likes to point out, ‘disabled’. I have worn hearing aids since I was a child. I was raised in a hearing culture, in the dominant hearing world. Although advanced hearing aid technology has afforded me the ability to largely pass as a hearing person, my life experience has made me acutely aware of the differences between how hearing and deaf people experience space. My regular day-to-day life flows on the invisible undercurrent of stepping between these two worlds. There are often times I feel unsafe walking around my city and in urban environments, a sense of heightened vulnerability because it’s easy to miss little or big things going on around me. The necessity to always stay alert slowly chips away at my energy levels, and by midday I’m already starting to wane.

Our cities and urban environments are simply not built with non-able-bodied people in mind. Here, I attempt to express what this means to me as a hard of hearing person living in a hearing world in Tamaki Makaurau, Aotearoa. The challenges I face along with so many others highlight the opportunities Auckland Council, planners, architects, and designers have to improve our public spaces for everyone.

d/Deaf and hard of hearing (d/DHH)[1] populations tend to navigate their urban environments differently than otherwise able-bodied people and this will inherently impact how safe they feel in public spaces. It is important for me to affirm that while hearing loss is widely viewed as exactly that, a loss, it is not advantageous to anyone, d/DHH or hearing, to view it in such a way. Instead, we should recognise that our urban environments are largely designed by and for the hearing person and hearing culture.

Challenges for those of us who have hearing loss are not limited to communication barriers. While a hearing person may be able to easily distinguish between background sounds, conversation and peripheral sounds a d/DHH person must expend a significant amount of psychological energy in an attempt to do the same. Every experience of hearing loss varies, and my words here are based on my own personal experiences and views. They do not define anyone else’s. Amanda Kolson Hurley (2015)[2] explains that hearing loss “isn’t a straightforward matter of all sounds being muffled or fading out. It’s a broad spectrum, from slight impairment to profound deafness. Often, it’s surprisingly noisy. Different noises override one another, and in fact, you can hear too much noise or distortion of noise.” Hurley helps us to understand that the d/DHH experience of an urban environment does not mean silent and neither does it mean hearing. This highly subjective middle ground is what makes hearing loss a difficult condition to understand without personal experience.

Navigating urban life poses many invisible challenges for d/DHH. Sensory stressors that naturally occur in urban environments are chaotic, often intensified by hearing instruments like hearing aids or cochlear implants. Sensory processing can be an intense, stressful and constant activity. Poor urban design exacerbates these issues for many d/DHH and often puts our safety at risk. Poorly designed or non-existent cycle lanes provide a clear example. Without good hearing it may be difficult for cyclists to identify the proximity, speed and reactions of cars nearby them. These stresses and safety risks could be reduced through designing cycle lanes to be protected with clear visual signalling for vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians.

The psychological stress that accumulates from the need to be hyper-aware of our surroundings is highlighted through the NZ Crime and Victims Survey (2018) which states that people who are ‘psychologically stressed’ are more likely to experience crime. While there is currently very little local research concerning d/DHH perception of fear in urban environments, d/DHH people are marginalized as part of the greater ‘disabled’ population, who are 4.2 times more likely to be a victim of violent crime (Statistics NZ, 2013). Marginalization and discrimination may occur in a variety of ways, but systemic and institutionalized marginalization can be some of the most disempowering, in particular the inability to exist safely in our built environments. The need to be hyper aware of your surroundings as a d/DHH person is more often about survival than enjoyment of space.

The ‘curb cut’ revolutions of the 1970s led by Ed Roberts in California led to acknowledgement of wheelchair users’ experience of space, improving the daily lives of wheelchair users worldwide. The acknowledgement of blind and partially-sighted populations’ experience of space led to the implementation of various tactile-based installations that have since become commonplace, including textured sidewalk transitions and audio-signals at pedestrian crossings. These adaptations pose the question: how can we improve urban spaces for those with other kinds of disabilities, perhaps for those of us who are non-hearing?

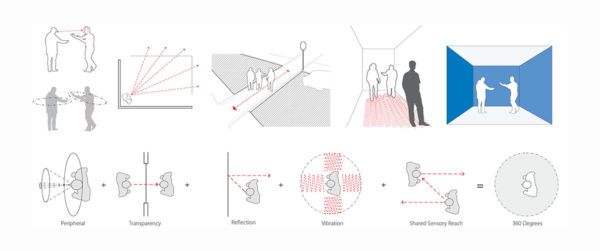

Academics at Gallaudet University in Washington, DC coined the term DeafSpace: “An approach to architecture and design that is primarily informed by the unique ways in which Deaf people perceive and inhabit space.” (Vox, 2016)[3] It focuses on a multi-sensory approach to the experience and design of space. DeafSpace guidelines encompass several key areas of interest[4]:

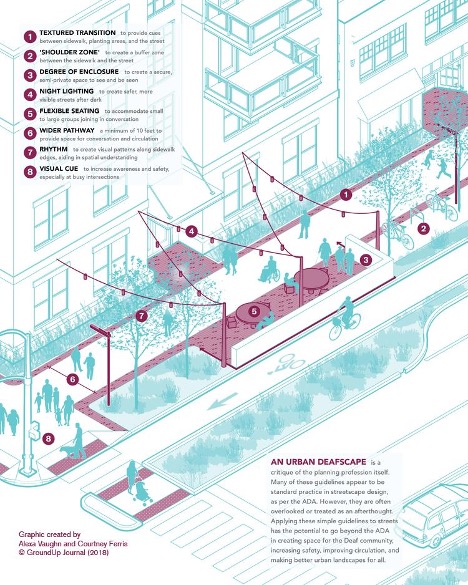

These principles may be applied to urban design, architecture, and landscape architecture to be more inclusive of non-hearing people and aim to create safer and more enjoyable spaces for everyone.

The Gallaudet University campus in Washington DC, designed by Hansel Bauman (2005), provides a precedent of thoughtful application of DeafSpace principles in an architectural and urban design context and can be explored in more detail through Gallaudet University literature[5]. Their design clearly acknowledged differences in d/DHH communication and movement styles, featuring:

- ‘conversation circles’,

- indirect lighting to minimize shadows,

- walkways with clear visual signalling, and

- strategic placement of mirrors and lights.

Deaf landscape architecture graduate Alexa Vaughn coined the term DeafScape, an application of DeafSpace principles to urban landscapes that demonstrate their potential in creating safer public spaces for d/DHH communities.

Currently, there isn’t much substantial research regarding the experience of space for d/DHH people in Aotearoa. Unfortunately, there is also little record of the application of deaf architecture or urban design in the Aotearoa context. This lack of data makes it difficult to understand the role that DeafSpace principles may have in our national and local contexts. However, lessons learned from Gallaudet University’s research and integration of these design principles offer insight into the potential of what Aotearoa’s cities could be like.

Auckland is often described as a diverse, inclusive city, with ‘improving liveability’ included as one of the goals of Auckland Council over the next 10 years. DeafSpace principles offer an opportunity to move a little closer to that. An inclusive city does not discriminate against perceived ‘ability’ and planners, architects and designers must open their minds to what they can learn from d/DHH culture and our experiences of space. By considering the accessibility and experience of space for our less-abled bodied and neurodiverse communities, we improve the safety and liveability of our urban spaces for everyone.

[1] Definitions:

- deaf: severe/profound hearing loss, may/may not use aids or use sign language.

- Deaf: severe/profound hearing loss, lives within Deaf culture, often sign language as first language.

- HH: hard of hearing: mild-moderate hearing loss, may/may not use aids.

- d/DHH: abbreviated term, including and acknowledging all types of hearing loss

[2] Hurley, A. K. (2015). What It’s Like To Be Hearing Impaired in a Big, Dense City. https://www.citylab.com/design/2015/09/what-its-like-to-be-hearing-impaired-in-the-city/405631/

[3] Vox. (2016) How architecture changes for the Deaf. [Video file.]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FNGp1aviGvE

[4] DeafSpace Principles. Gallaudet University.

[5] https://www.gallaudet.edu/campus-design-and-planning/deafspace/

Processing...

Processing...

Great article, Camilla, thanks.

Public spaces and streetscapes should absolutely be designed with best practice principles in mind for a variety of impairments (mobility, visual, hearing etc.). It must make it really challenging for designers but it’d be worth it. Everyone, including able-bodied people, benefits from safer, easier to navigate and less stressful streets.

Thanks heaps, Camilla. I learnt lots :-). So easy to see how multi-sensory planning will make everyone’s lives better, too. My son has autism, and the use of more visual cues is super helpful for him, too. And in my transport and mental health research, lots of people talked about the need to think about how we can make our cities more ‘restorative’ and reduce sensory overload, and noise in particular.

Great post. Good to see someone talk about the issue facing deaf. I am deaf and I wear hearing aid

There are lot barriers facing deaf people.

– when there is an public announcement whether on the trains or waiting for the trains, I can hear it but can’t understand it what the talking is about. I often ask a member of public to explain what this is about. I have a twitter account but the information are quite slow.

– when walking along a cycleway, the cyclist will shout to warn me but I can’t hear it till it is too late. This is why I walk to the far left if possible and keep looking behind me from time to time.

– I cycle to work few times a week and often rely on visual check, that is sometime checking behind me before passing a parked car on the side of the road. I often can’t hear a cyclist behind me.

– It is very hard to lipread and walk at the same time without tripping over. Sadly most of the footpath in Auckland are uneven and in some place are narrow. We can do sign language but we need to look where we are going to make sure that path is clear.

Yes, it is a great post. Thanks for your comment too, Ian.

Basically, we need far better infrastructure.

Hearing loss is setting in plus I have a of a hole in the vision of my right eye. But yesterday I was looking about for something to do so I settled on a bike ride on the new Southern path. So a 1 km ride to the station then on to Te Mahia 200 metres on the footpath two intersections and I am on the path. A southerly head wind plus the gradient slowed this pensioner down at one stage I was overtaken by a runner. Made it through to Beach Road went into the service station but $7 sandwich no way so ride into Papakura to find something cheaper. On the train and home. And slept real well last night. Its a bit messy at Te Mahia and I stuck to the footpath in Papakura it didn’t seem to unsafe with only a couple of pedestrians who I gave way too. Traffic on the path was sparse one runner two walkers and four bikers plus myself. So hardly a main traffic artery still it early days. I am more concerned with my eye sight than hearing but that could be fixed if I fitted a rear view mirror. Main problem just not enough leg power although I consider myself reasonably fit as I regularly walk up to 10 thousand steps. I don’t think I will save up for an electric bike but you never know. My worry would be leaving a 3 or 4 thousand dollar toy outside a even if its locked up.

🙂 I have a rear view mirror and it really helps. On the shared paths, yes, because I’m overtaken a lot too. Also when wanting to turn right off a road and needing to concentrate on broken tarmac, road crash debris and both oncoming and turning traffic, use my arm to signal while braking (if going downhill especially) yet also keep ahead of what’s happening behind…

I can’t imagine attempting all that with any hearing loss.

Thank you so much for this – I keep trying to elevate the need for universal design in projects but so many enginners just dont get it. It isnt on their checksheet. Its a ‘principle’ rather than an engineered requirement and allows obfuscation.

I still see new AT projects (roudabout at Deep Creek / Firth) that dont even have kerb cut downs. There is just no requirement or review for universal design factored into ‘the system’ and its borderline non-complying with UN charter of Human Rights.

NZ we need to do much better.

Thanks for the post. Where I live we have been lobbying the council for a year to remove a key kerb that makes it difficult for prams and wheelchairs to cross a local road. Seems hard to get these small change jobs whereas nearby 100 trucks work day and night to finish off Transmission Gully.

What I find hard to fathom is why so many people with normal hearing deliberately impair themselves with headphones, ear buds or other such devices. Having tried using an old-style ‘Walkman’ out in the street many years ago, I was so struck by the reduction in situational awareness it caused that I soon ditched it. I feel for those whose impairment is not from choice, but those who intentionally drown out their hearing seem to me to be daft.

Absolutely agree. I thought it might be fun to have some musical accompaniment when I go on my regular long urban walks, but I very quickly found the lack of situational awareness positively dangerous. Now I reserve the ear buds for the gym.

Totally understand where you are both coming from, it seems counter intuitive but I love listening to music with headphones on when I’m out and about partially because it reduces my anxiety. Sometimes I feel quite vulnerable and afraid of strangers and the headphones and music make a barrier between me and strangers, buffering me from the world and enabling me to go outside & shopping etc. It reduces the social pressure to interact if someone tries to talk to me, and the music itself is familiar and soothing.

I don’t want to trivialize important issues, but:

Ear buds/ earphones = hearing impairment

Looking at phone = visual impairment

Conversing/thinking = cognitive impairment.

Inclusive design benefits everyone, so there is a huge benefit value to any measures that deal with the problems faced by anyone with an enduring impairment.

A post like this does show how important it is to set out and explain these aspects of design in Guides and Codes, so that Inclusive Design becomes standard practice.

What we need to identify across the spectrum of sensory abilities and experiences are the synergies and conflicts. For example, yellow tactile tiles at crossings benefit d/DHH as well as visually impaired, but can be uncomfortable for some mobility-impaired people. Too much visual ‘noise’ as well as audible noise can be a problem, but is often there to add ‘interest’ to a space.

Finding a means of setting down design principles, as done for Deafspace, can make it easier for designers and reviewers to produce inclusive spaces. Identifying barriers is a first step (once called “Barrier Free design”), but not sufficiently positive to become truly inclusive design.

Got woken up at 6am. Car crash outside my window. Corolla on wrong side of road. No injuries – just two mashed cars. Heard the corolla didnts see the black suv parked on side of road – due to fog on windows. We dont need ear/eye deficiency to be involved in impairment accidents.

Crossing Gt Sth Road walkking with my 12yo son today – no footpath and bridge squeezing traffic. My eyesight crashing with age, my long glasses back in my car. Safe designed footpath spaces, are even more important when all our roads are 120% full and optimised for speed – nobreaks. nomercy. nosightlines. Crazy even with with 20/20 vision.

Great post, thank you! I have experienced hearing loss over several years and weat hearing aids. It was so nice to see someone talk about how exhausting all the noise is in an urban setting when you have hearing aids in, and the constant hyper alertness about one’s surroundings – especially as a female. I also cycle and would love more separated cycleway a so I feel safer.

Thank you Camilla, I learnt a lot reading this.

Thanks Jacquie! x

Malls don’t usually have reptile-guide.com

outward-facing shops*. We could force them too as a condition of consent.