This is a guest post by Meredith Dale and Greer O’Donnell, The Urban Advisory.

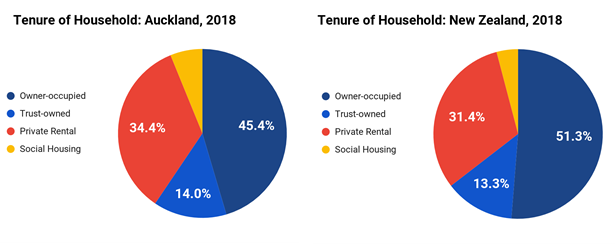

Housing in New Zealand generally falls into one of three tenure groups: home ownership, private rental or social housing, with a limited amount of community housing (Figure 1).

The housing system is dominated by for-profit development, creating housing for owner-occupiers or investors seeking a market rent. The remainder is largely public (‘state’) housing, plus a little community housing, which itself largely depends on government funding and the social housing register.

There’s a growing discourse about the challenges this system presents for moderate to low income households, with a severe undersupply of housing options which are secure, good quality and affordable for them. In 2018, 40.2% (95,400) of renter households in Auckland, or 16.5% of all households were ‘stressed’ – that is, unable to afford to buy a house at the lower quartile house price and paying more than 30% of their income on rental housing. These households fall into the growing Intermediate Housing Market category, with little option other than to end up on the social housing waitlist or endure expensive rental options in the market.

There are several types of housing overseas that could serve the Intermediate Housing Market, many of which are almost unknown in NZ. One development model that is starting to provide options for these households, and getting a lot of media coverage, is Build-to-Rent. However, there are also other options, such as cooperative housing, which are poorly understood in New Zealand, and are struggling to establish roots here because of our legislative frameworks, monetary and fiscal policy.

What are Build-to-Rent and Cooperative Housing?

Build-to-rent (BTR) are multi-unit residential developments that are designed and built with long-term rental in mind (rather than selling to residents as unit titles to own). Tenants benefit from long-term secure rental, often tailored to a specific price point or ‘market’ rent, and assurance of a reliable, professional landlord. In turn, investors receive a return on their investment for financing the project.

Cooperatives are housing developments where residents own a share of the housing cooperative, which allows them to have a legal interest in, and access to the property, as opposed to owning a title to an individual unit. Purchasing a share creates a pool of resources for the cooperative, which can be used to pay any existing mortgage, cover maintenance, management, services and provide collectively held amenities. This shared approach can reduce the cost of living and, if desired by the cooperative, can be designed to offer affordability, providing a third tenure option between pure ownership and rental. For more info, see The Urban Advisory’s crash course introduction to cooperatives.

Long-term, affordable rental tenure options like cooperatives and BTR support residents to ‘put down roots’ in their neighbourhood, and be involved in their community. At the regional scale, BTR and cooperative housing improve the quality and supply of rental housing by creating new warm, dry homes that are professionally managed, and consequently they improve overall community health and wellbeing with associated economic productivity, education and healthcare benefits. What BTR offers to the rental market is a stark contrast to the realities of rental housing in NZ at present. Renters often live in older, poorer quality houses with insecure tenancies; issues that are only just beginning to be addressed through recent policy changes.

BTR and cooperatives are often produced as medium to high-density housing typologies (e.g. apartments, terraced housing), but that isn’t always the case. There are examples of lower density build-to-rent emerging in New Zealand, with New Ground Living, who has been providing BTR for Aucklanders since 2014 moving into more detached typologies for BTR development. More recently several other forms of BTR development have emerged, such as 26Aroha in Sandringham (a ‘mum and dad’ developer who wanted to deliver a more sustainable housing product) and Modal by Ockham Residential in Mount Albert. The cooperative housing agenda is being advanced in small pockets in Aotearoa too, most notably by CLOSER Developments, in Katikati.

The Future of Build-to-Rent

Build-to-rent has been popular in the UK and Australia over the last decade, but has not yet taken off in New Zealand. However, a recent report from JLL records a growing appetite for build-to-rent in New Zealand among local and international investors. This is an important point, because pre-COVID, multi-unit residential and higher density development made up a large proportion of approved consents in Auckland (Figure 2), contributing significantly to our growing housing supply. Indeed, high-density housing is a critical piece of the housing shortage puzzle we need to solve in Auckland, and BTR developments are likely to be part of the solution. It seems that in post-COVID times, BTR is an attractive new prospect for investors and developers alike.

For renters, BTR also delivers something the market has in short supply: high-quality, secure long-term rental housing. And for the overall market, BTR encourages a more stable and resilient housing system. These benefits of BTR should not be underestimated: stable communities and healthy homes improve wellbeing outcomes for individuals, families and overall productivity, education and healthcare outcomes.

Current market projections for a growing BTR sector focus on the commercial investor-only model of BTR for NZ, however some developments still require a government underwrite or other forms of support. This has been raised with the government, who are looking into what they can do to enable the sector to scale.

The same challenges (and more) are hindering cooperative housing in New Zealand. For a more detailed look at the cooperative model and the challenges facing cooperative housing development in New Zealand see our report: Cooperative Housing.

Internationally, this sector is supported through both public sector funding (state or national, philanthropic and impact investment sectors), by banks providing longer amortisation periods, and ‘patient capital’ (low interest, over a long time period) from investors with social responsibility criteria, like pension funds. In Canada, for example, the Mortgage and Housing Corporation has a seed fund to support cooperatives. In the UK, the Community-led Homes programme offers funding at support at every stage of the development process, in acknowledgment of the benefits these tenures provide to communities.

Confused about the difference between BTR and cooperative housing?

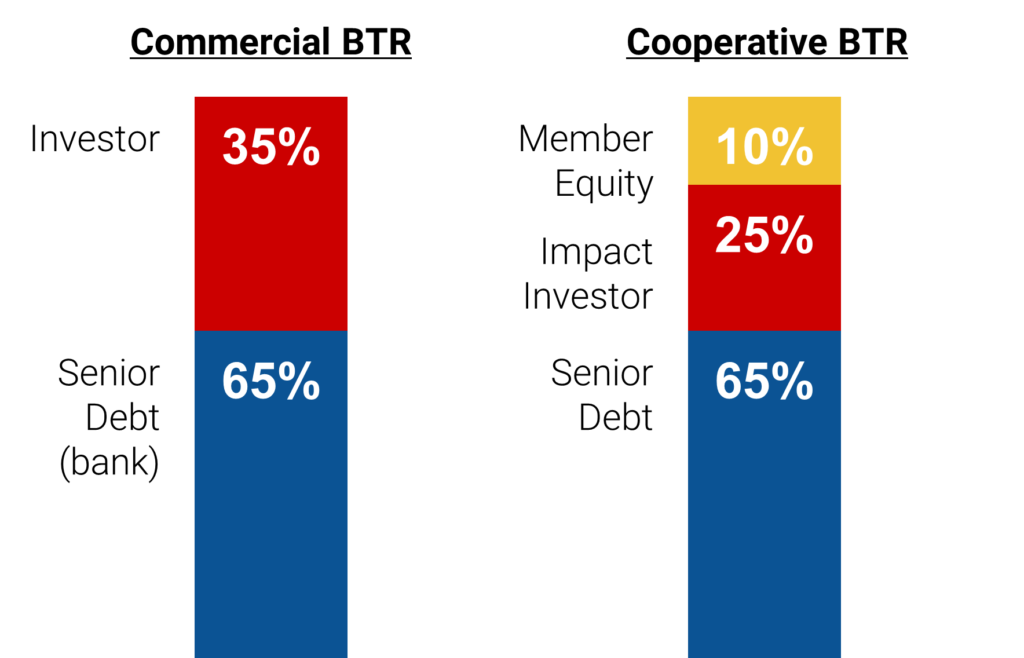

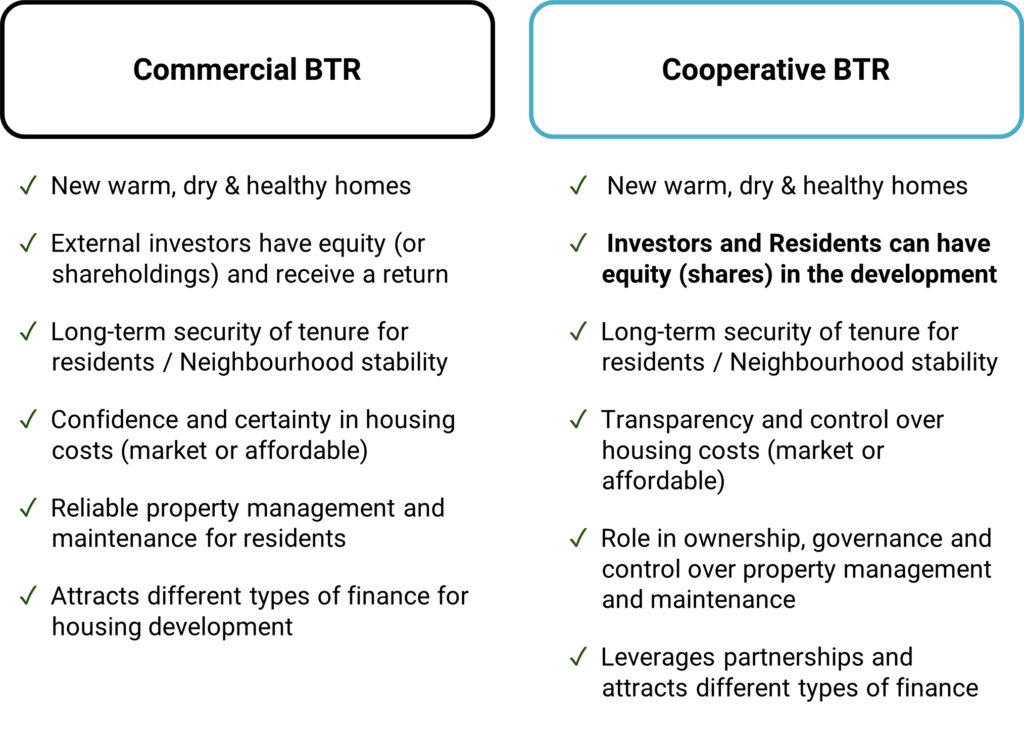

The main difference between commercial build-to rent and cooperative housing is the cooperative governance, management and financing structure, that provides the opportunity for co-op residents to have both an ownership interest through an equity shareholding in the development, as well as their leasehold ‘rental’ interest (see figure 3).

Because of their characteristics, cooperative developments have a capacity and track record of attracting more diverse types of capital and investment, e.g. through impact investors. The below table provides a high-level overview of the key differences between the two development models.

The post-COVID environment and growing pressures on the housing market, presents an opportunity to work with the government to diversify the housing ecosystem, scale the BTR model and remove the barriers to cooperative housing in New Zealand.

Further work is required on what the appropriate support for BTR would look like. It could start with a commitment to support existing projects, through seed funding, capacity building within government organisations, development capital, underwrites or guarantees, and preferential access to leasehold land under The Land for Housing Programme. To ensure an enduring bi-partisan solution however, consideration should be given to what fit-for-purpose legislation and finance settings would like, that make BTR both commercially viable for developers and investors, and fair for residents.

Processing...

Processing...

Imagine if we put the same passion and expertise into solving our housing and climate emergencies as we do into yachting.

Imagine if we weren’t all sad sacks and realise that it isn’t a case of one or the other but that both are possible.

Imagine if we didn’t have to imagine but had a track record we could point to.

Yes. So funny. And that cycle routes stuff in London also impressive and actual track record.

Winning at yachting just involves solving a lot of technical problems. That’s easy.

For our housing and climate emergencies all the technical problems have essentially been solved*. Resolving these emergencies requires implementing the solutions and this implementation creates a myriad of political problems. Political problems are really, really hard. As evidenced by the lack of progress on these issues.

( * The reason that research and development on technical solutions continues to be done is that we are looking for technical solutions that are politically easier to implement.)

+1

The housing and climate emergencies are solved. We just need politicians to take action.

Yes. Well put.

And for politicians to be able to do that, we need the general population to see that the “problem” (poverty and the inability to work your way out of it) is worthy of the “solution” (removing land as a vehicle to accumulate effortless wealth). But any sniff of a chance to do that, like the Tax Working Group daring to mention a land tax, and it’s shut down immediately by the PM to prevent political suicide. It’s so easy to blame politicians, but they mostly just reflect the electorate. Ditto on climate change.

Yes, but that’s not the full story either. Good leadership involves harnessing the public’s wider goals – which include providing for our children and improving our social and environmental outcomes – by ignoring or skirting around the short term hurdles and popularity contests. To achieve those wider goals, good leaders take risks, in a way that sparks hope and allows people to emerge from their shells and stand up to be counted.

Our PM – as others have said – is like a great battlefield leader. But she has yet to truly lead in a properly democratic way that seeks out the people offering a solution to our challenges. She has trodden a politically conservative path and hasn’t listened to the more fundamental truths and more vulnerable voices – but to the more conventional narratives and the more arrogant voices.

Good in theory. But when “the public’s wider goals – which include providing for our children and improving our social and environmental outcomes” amounts to amassing a fortune to leave our kids and having our own private lawns, then liability-free property ownership seems like a human right to the masses, even if it is actually counterproductive to those very goals. If we can get the masses to understand and act on that, I’d hope we’re home.

If only Council invested as much in housing as AT/AC do in car parks.

The THAB zone is making a big difference. I have been working on some BTR projects recently that wouldn’t have happened without the THAB.

Its making a big difference in supply. We just have to make sure it works for us in terms of better neighbourhoods, less car dependency etc..but definitely seeing hundreds of large single story lots fenced off ready for demo in these THAB areas these days.

A non-cynical post by Miffy. I’m shook.

I think his account has been hacked

“Hacked” you can put in whatever name and email you want.

(Not miffy)

The rent in that Aroha development is very high, so I laugh a bit at their ‘social objectives’.

Cooperative models are quite interesting.

I would like to see the government build a lot more shared equity housing. It gives people an ownership stake, plus security of tenure. Plus outgoings are much lower than rental outgoings.

Yes guess we are still at stage were limited supplies equals high prices. In Te Atatu we have a development of 11 x 1 bedroom units for sale – nothing built yet but advertised as all sold. The advertising material was stating a rental yield of $700 per week. are we going like the UK were rental properties are a solid investment as rent is paid by government to solve housing shortage ?( Blackpool is the example were all the old B and Bs are now multiple occupancy dwellings) Genuine question as I don’t know how system works.

$700 pw for one bedroom, no way! Things are insane but not that insane!!!

“Patient capital” is the key. Mum-and-dad need a retirement income. Accumulation of lots to enable building at economical scale for BTR, or for Co-op, needs to be taken away from the “quick return” investor market, where silly prices are showing up.

I was one of the architects for 26 Aroha, and fortunate to live in it now. While the rent looks expensive on paper, you have to factor in the savings through not having a car, high level of insulation, solar hot water, shared car, shared laundry, internet and shared garden. The expenses after rent, are half of what we were paying previously in a standard apartment in Eden Terrace. Then there’s the use and maintenance of the shared spaces, which is incorporated in the rent and therefore requires a change in mentality in treating the shared spaces simply as an extension of your own apartment. It’s a good time, we have dinners and general social events on the rooftop regularly. On top of all this, it’s important to note that the rents are market rate.

What is the rent?

We’re paying $690pw for a 2 bed. It’s 74m2 with a 10m2 balcony. Notably larger than Ockham 2 beds.

Cheers for the reply. I’m also interested what’s the story with the car?

It would be nice to not have to own one and I’m interested in what solutions / models are around.

But my sport is Tramping / Mountaineering / Climbing, usually distant from Auckland. And leaving a vehicle unattended at road ends for a few days.

Probably not compatible with many schemes like this.

Thanks for that, fair points. However it’s still a bit cheeky proclaiming it’s social equity attributes at that rental price.

It’s got some innovative attributes, but it’s not doing anything for social equity.

The 2 bedroom apartments are large, at 71-98 square meters. Why couldn’t they be smaller and more affordable, when there are generous communal areas?

This is quasi sustainable housing for the middle class.

Apologies, I was a little harsh. It’s a good project, a more sustainable middle class project is of course preferable to an unsustainable equivalent. The social equity claim does bug me, though. People who are interested in this stuff but with a much more genuinely equitable approach should check out Christie’s Walk in Adelaide.

It’s a valid question, but this isn’t social housing.

No 2 bed’s are 98m2 also, they average mid 70’s.

The client required bank funding, so in order to secure the funding the building and individual apartments have to be of a certain value, this in turn pushes up the apartment sizes. It’s unfortunately how the private market is so heavily persuaded by bank security.

Developers like Ockham can reduce this through their funding model and existing equity. That being said, they arguably have very little storage. If you’re designing small, you’ve really got to maximise storage through inbuilt cabinetry etc.

I was going by the 26Aroha website which specifies the size range of 2 bedroom apartments between 71 and 98 square meters.

Also the rents for studios is above $500 per week, that’s pricey.

I realise it’s private market accommodation, not social housing, but maybe it could have been done differently to be a bit less pricey…

Those two residential developments look like what you’d see in Australian cities.

There’s a shared electric car which is bookable at an hourly rate.

Plenty of residents park on the street, or just Uber, it’s not a problem.

Very quickly becomes a problem if everyone intensifies and expects to be able to just park on the street.

Very quickly becomes a problem when apartment developments are driven by car park yield. Easy solution, provide a number of shared vehicles and rental services.

But less of a problem than if we sprawl instead to achieve these homes. And a problem that has solutions.

Agree

Liam – thanks for your replies, I’m interested to know more. What are the apartments built from – concrete frame? What about internal / inter-tenancy walls? External cladding? And how do you get light and air to the second bedroom? Individual HWC or a combined apartment wide hot water system? And lastly, acoustics: how did you prove that the desired acoustic ratings were achieved? Lots of questions, if you can answer, that would be great.

Hi Guy (Marriage??)

The apartments and primary structure is concrete block 20 / 25 series.

I.T walls are 25 series, exposed and honed. Floor slabs are concrete rib, that we left exposed on the upper levels to increase volume. Ceilings in the living spaces generally are 2650 and 2550 in the bedrooms.

External cladding is mostly profiled metal (Top Deck T in reverse). In the core the cladding is Fundermax. All bedrooms have a window, there’s no borrowed light. There’s a central solar hot water system, so no individual HWC’s. The 4 solar hot water panels on the North block provide up to 70% of the power for the hot water system. Acoustics, Marshall Day do on site testing once complete. This is required to prove the designed floors and walls reach building code minimum.

Thanks Liam ! Much appreciated. (Yes, Marriage)

No problem Guy! I’ve messaged you on LinkedIn 🙂

Just a thought, but could the new developments that we are getting enthused about here, also include special recreation areas to stop their occupants going stir crazy. We need to look at the modern developments in senior citizens complexes, where, in addition to social rooms, swimming pools and bowling greens and mini put courses, there are metal and woodworking workshops for those who want to work with their hands.

You have explained very well regarding the better renting through new housing models. The one who is going to plan, buy a new house this is very helpful blog. Thanks for sharing it with us.