Auckland’s current rapid transit network (RTN) is fairly limited in its reach and quality but the region has some big plans for developing it going forward, some aspects of which are already under construction. Importantly and positively, over the last decade we’ve seen a big shift in thinking from central government. Processes like the Auckland Transport Alignment Project (ATAP) has seen successive governments agree on the need for the RTN as well as some rough priorities. Furthermore, most of the political parties that are either currently in parliament or likely to make up the next one include some form of RTN expansion of it in their policies for the upcoming election – ACT doesn’t explicitly include it but doesn’t rule it out either.

Buses and busways will play an important role in the future but things differ on how and where we expand the role of rail in the region. For the purpose of this post, there are two main schools of thought on this, we:

- expand the existing heavy rail network; or

- introduce a new form of rapid transit, such as light metro or light rail.

We’ve seen this debate play out for almost six years after light rail re-emerged as an option being seriously being considered. In this post I want to focus on why we should introduce a new form of rapid transit

Expand the existing network

From Britomart to double tracking to electrification and now the City Rail Link, we’ve been spending, and are going to continue to spend billions on improving it. At $4.4 billion the City Rail Link alone is currently the single biggest transport project the country has ever undertaken and the project is needed to unlock capacity on the network. It will eventually allow up to 54,000 people an hour to arrive in the city centre by train, up from just a maximum over 14,000 currently. Although, to achieve those numbers significant additional investment will still be required such as signalling upgrades, level crossing removal, more trains and longer platforms.

The main argument for expanding the existing network is fairly straightforward, that we should make the most of the nearly four-fold increase in capacity the CRL allows for to serve areas not currently on the network such as the North Shore and the Airport. Other arguments often include that it allows for fleet interoperability and a wider variety of network designs.

On the surface this can sound practical or like “common sense”.

Introduce a new network

As noted above, when it comes to rail this could be in the form of light rail or light metro, both of which have been discussed here many times. Below are some of the reasons why building something different to what we currently have is not a bad thing.

Resilience

If there’s anything the last few months has shown us with both the rail network and Harbour Bridge, it’s that we shouldn’t put all our eggs in one basket. The CRL is a fantastic and much needed project but even with it, our network remains very skinny and with still just two tracks at its core – a far cry from the sometimes lavish rail resource available in other, often older cities.

That skinniness means a single issue, be it a train breaking down, a signalling fault, a medical emergency, or a range of other things, could grind the entire network to a halt. Most regular rail users will be very familiar with the chaos that quickly spreads across the network when there something goes wrong at Britomart.

Introducing a new, independent network doesn’t stop issues from happening but it does mean when they do, the core of the entire regions PT network isn’t taken out of action.

Network Design

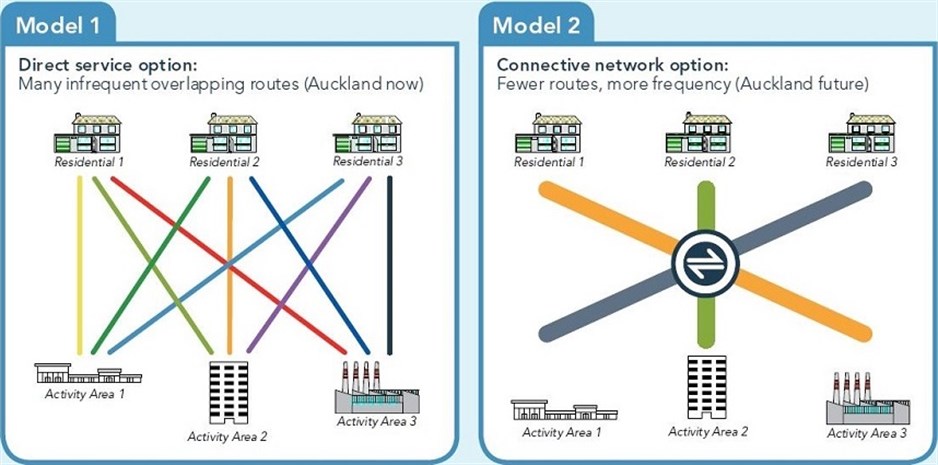

Somewhat related to resilience is also the issue of network design. It’s one thing to be able to run trains from every line to every other line but that can mean you may end up with long waits for the exact service you want. By comparison, by having just one or two routes using a piece of infrastructure like the CRL it means you can run each route at very high frequencies. With the new independent network also operating the same way it would only require a quick and simple transfer to get to a destination served by it. I get that some people don’t like transferring but it is standard practice on metros around the world. I’d challenge people to point to a well-used network that doesn’t do this.

If people can easily transfer between services, that also means there’s no requirement that both those services be identical in design, just function.

Of course, this kind of network principle is the same thinking behind the successful bus network changes implemented a few years ago, where the graphic below comes from.

This network design philosophy also applies to future intercity trains. Why would we divert a train to serve an area many of its potential users don’t want to go when they could easily transfer like locals do.

Capacity

As mentioned, the CRL provides for a nearly four-fold increase in capacity, but if we’re going to met our goals for the city and the climate, we’re going to need every bit of that just to serve the existing network.

Auckland’s Climate Plan sets the target of us needing to increase the public transport mode share to 24.5% by 2030 and to 35% by 2050. That’s a huge jump so let’s put that in perspective.

Prior to Covid we had just over 100 million trips annually on PT and that is estimated to equate to about an 8% mode share. With our currently expected population growth it means that by 2030 we need our PT system to be moving nearly 400 million trips annually and by 2050 that increases to almost 700 million trips. In other words in 30 years we need our PT system to cope with seven times the amount of trips it was doing prior to Covid.

I expect the current and future RTN will need to play a substantial role in achieving those levels of growth, much like it has over the last decade. Of course, you’ll note that a seven-fold increase is much larger than the four-fold increase the CRL allows for. Catering for much larger future growth is one of the reasons for the extra cost of the project by allowing for 9-car trains and I think there are further opportunities for increasing rail capacity, such as metro style seating. However, I also suspect a large chunk of that growth will come from making our PT network more viable off-peak and on weekends.

Capacity issues also apply to the argument about depots too. We originally bought 57 electric trains and have almost finished receiving our second batch of 15 to bring the total to 72 trains. Depots don’t have unlimited capacity though and our current one was designed for a maximum of 109 trains. We’ll need that depot capacity for all the extra trains we’ll need for the CRL. But that also means there’s no capacity available in the depot to also serve new lines. That means any new line we build will need a new depot anyway.

Design Standards

If based on all of the above (and more) we know we’ll need a new dedicated new line we finally need to ask ourselves if we should be saddled to legacy design standards or if we shouldn’t instead use something more modern and fit for purpose of moving people. These more modern systems also have the advantage of allowing for things such as steeper gradients and sharper curves, things which could help make such a new line cheaper and easier to build.

It’s here that we can also look to other cities and see that building new lines and modes that are not compatible with what we’ve built in the past is actually very common. For example, just over the ditch in the West Island, Sydney has added recently added two new modes, metro and light rail, that are incompatible with their existing networks. Bigger and older cities like London, Paris or Tokyo are patchwork quilts of different designs from different eras. What they have in common though is each of the systems perform part of a cohesive network.

We need to not be afraid of having different modes, if anything, they should be embraced as they could potentially open up new opportunities.

Processing...

Processing...

Until central government ceases meddling in the design and implementation of local transport initiatives, Auckland will never succeed in a high quality network.

City state time!!

Only half kidding, aside from power generation (which could be fixed with a few atoms) and food production issues, Auckland could totally be a viable city state.

It would be an interesting thought experiment at least. Wouldn’t be beholden to Wellington, could have our own central bank with much more appropriate borrowing capabilities.

Auckland is not self sufficient in anything except clean air. You can’t survive as an independent city state without Waikato’s water, or Hawkes Bay fruit and veggies, or Taranaki milk and cheese, or Otago pinot. Or, for that matter, Samoa’s hard working immigrants, and a fair dollop of the rest of NZ’s money….

So, good luck with that.

All the above also applies to Singapore

NZ can’t survive without the world’s cars, oil, electronics but still functions perfectly well as an independent state.

I don’t support Auckland being a city state but producing everything yourself is not a prerequisite.

Auckland as a city state could trade with NZ for all the goods it needs. However trade in services would be the biggest barrier to Auckland seceding from the rest of NZ.

Most of New Zealand’s financial services firms are headquartered in Auckland’s CBD. The major banks, insurers, stockbrokers, consultancies, law firms etc. All of them would be hindered by having to operate across two different legal/regulatory/tax systems. The additional costs would have to be passed on to their customers, ie everyone.

My tongue was firmly in my cheek when I said that, in case that wasn’t obvious. But digressing slightly, I’ve done a bit of study into one particular city state, that existed for almost 800 years – the city of Ragusa, now known as Dubrovnik. It was a tiny wee place, surrounded by city walls, and fairly impregnable from attack due to the walls. Key point is that it survived all that time by means of trade – very much focused on being the good trading partner of both the Turks to one side of the mountain and the Catholic Italians to the other side of the sea – and still maintaining a working relationship with the Venetians who ruled the whole area by sea.

Auckland is a modern version of that. It relies hugely on trade. On not pissing off its neighbours. On spectacle, on worshipping of gold, on being the flashy dresser, on being the banker for all the neighbouring areas, but most of all on trading with everyone, to make sure that they can survive.

New Zealand could survive without a steady stream of new cars from offshore (although arguably that is a habit we should perhaps try to kick), but a city without water or food or a means of creating your own electricity wouldn’t last long at all.

So until a city state is created, free from those awfully restrictive laws created by Auckland politicians working in Wellington, you’ll just have to stay trading with the rest of the country. So, let’s be nice…

Matt, well thought out as usual.

Can I also suggest that a just as important challenge will be to have mechanisms that encourage individuals to use our networks. I note that the recent edition of Vienna in Figures shows that the number of annual pass holders sits at 852,000, up from around 800k. If Viennese people were behaving rationally they would only be buying an annual pass if they intended to do four trips a week. What number of trips would persuade anyone to buy a Hop Card – four a year?

It would be interesting to know the uptake of annual passes in Auckland. I suspect it is likely to be different by a figure of a thousand, that is, somewhere near 852.

The resiilience argument does not work.

Having two networks only provides additional resilience if the same journeys are possible using the two independently. That means that service frequency and geographical reach have to be sacrificed to achieve resilience within the same budget. That won’t happen and shouldn’t happen.

If the two networks have different geographical reach, resilience will be improved in some cases and made worse in others. Journeys possible on either network can be undertaken on failure of either. But a journey which requires two independent signalling systems both to be working becomes impossible on failure of either of the two, which is worse than relying on only one.

The limited geographical resilience of Auckland’s high-tension power supply would also act as a shared risk to both at the same time, unless of course money is diverted to fixing that. Which is the same tradeoff against quantity of services.

The definition of a network is a system of lines but with a number of nodes that together make alternative routings possible.

Think London Transport, or the internet. Partial closures can then be bypassed except in their outermost extremities.

It is these alternative routings that give the resilience lacking in Auckland Transport at present.

The thing I’ve never understood about Aucklands rail network is why there isn’t a centre passing track at most train stations.

Melbourne rail stations have this 3rd passing track which allows express trains to bypass trains stopping at every station.

Just seems sensible to jem

Which stations in Melbourne are you thinking of? The only ones I can think of are those with an express track for the V-line regional trains. The majority of stations in Melbourne have only two tracks.

Passing tracks at stations are pretty useless as trains usually need to maintain a decent gap. Even in a perfect system with no delays the all stops service would need to wait about four minutes at the station to allow the express to catch-up, pass and then get far enough ahead.

Jezza: I used to live on the Lillydale line.

Although now that I come to look into it, the 3rd passing track isn’t as prevalent as I thought… in that not every station has it. However many do such as Box Hill, Blackburn, Ringwood etc.

Still, being able to run express trains remains a good idea even if it does complicate scheduling. Its also important to remember that goods trains continue to operate on many sections of Auckland’s rail corridors.

I’m not sure about Box Hill but some services terminate at Ringwood and Blackburn, the extra track is used to keep these trains off the main line.

I agree about express services but they really require an extra track (or tracks if you want to run them in both directions) for all or most of the express section. From memory Lilydale express trains pass all stops services closer to the CBD where there are four tracks.

You’re right about freight trains, which is why Kiwirail are currently in the process of building a third main line between Westfield and Wiri.

Jezza: The Box Hill station box is huge. It has room for a 4th rail (uninstalled) and a 4th platform (built but unused).

I definitely recall passenger trains rocketing through stations either on the normal rail or via the 3rd passing rail. I’m not sure if these were passenger carrying services or not. I also (as you indicated) recall trains parked up on these 3rd rail lines… although for some funny reason my memory records them as being on a curving section of track… I may be thinking of a larger station such as Camberwell.

An argument for increased topological diversity is not an argument for a separate network. And a lower-capacity link cannot reliably act as a replacement for a higher capacity link without service degradation.

(In telecommunications networks. prioritisation of traffic is central to the way service degradation is designed for, with most Internet traffic allowed to experience degradation before voice service is affected. This permits the same network to offer different levels of resilience to different services. There is no easy equivalent in road or rail networks.)

There is so an easy equivalent in road or rail networks: User behaviour.

Auckland Harbour Bridge reduced capacity: Widespread communication to this effect from NZTA/AT. People avoid making the trip if possible. People delay travel to offpeak if possible and/or reroute to the Upper Harbour Motorway. People who still need to travel at peak just put up with the reduced level of service.

Auckland railway shutdown: Widespread communication to this effect from AT. People avoid making the trip if possible. People delay travel to offpeak if possible and use buses. People who still need to travel at peak use buses and just put up with the reduced level of service.

If one mode fails and another mode experiences service degradation from overloading, then this is acceptable in the short term. Additional independent rapid transit lines just decrease the degree of overloading and thus decrease the service degradation that results from failure of any one mode.

LogarithmicBear has the best take in resilience here. The ability for the most critical activities of the city to continue through a degradation of service is the objective. It’s where the Second Harbour Crossing knee-jerk fails – we don’t need duplicate capacity, we just need adequate alternatives for ‘coping’.

The additional network case needs to be examined in this context – the extent to which it enables the city to cope, when one major degradation happens somewhere. The question may be: does the alternative network mode option provide a coping mechanism? If it does, then it should be a good thing. However, if alternative route capacity on existing networks can cope, then not so much. WE’ve had some pretty good examples lately of what ‘coping’ means.

Actually I disagree.

If you study Sydneys Metro Network, you’ll find that it duplicates much of the existing Heavy Rail network both north and south of Central.

So there is precedent… although exactly why its been designed in this fashion escapes me.

In Auckland’s case, there is need for rapid transit for many areas notably Dominion Rd/Sandringham, further east beyond Panmure the North Shore, out to the airport etc

As heavy rail was developed long before the population centres developed, retrofitting these areas is likely to be problematical. So mixed mode public transportation is all but inevitable as is duplication to some degree of existing routes.

Despite the cost, I’m in favour of grade separated Light Metro. The trouble with Light Rail is that its subject to the same traffic jams that surface traffic is.

I just wish that the government would get off their chuff and do something. We’ve already lost 4 years dithering around. Hopefully we won’t burn off another 4 years with nothing to show for it.

BTW As a telecommunications engineer myself, the analogy between telco networks & rail is a poor one. IP networks carry mixed mode traffic, something that doesn’t happen on rail.

Southern heavy rail line fails. I take the Eastern line. They both fail I take a 70 bus into the city. If light rail went down one of the Isthmus roads like Dominion Rd etc I could take the 66 bus and transfer to that. At the moment I could use the 30 bus say along Manukau Rd. That’s good temporary resilience.

Add in a cycling network, too, and a good chunk of people would use that, ensuring those who can’t aren’t held up in overloaded buses, too.

Sydney have recently added a second line of light rail, the existing one L1 City to Dulwich Hill was built and then extended some time ago.

I also think that resilience also needs to encompass having different fleets, particularly as technology increases within a vehicle, meaning that a glitch in software can stop an entire fleet, particularly as new vehicles/fleets are introduced. An example probably more relevant is would a second fleet include retractable ramps or would you have level boarding to assist less able passengers to board?

The retractable ramps are actually a network issue. They are required as the rail platforms have to allow enough space for freight wagons to pass. A new light rail network wouldn’t need to account for this so would likely have level boarding in at least some parts of the vehicle without needing ramps.

Other things being equal, one network is as resilient or more resilient than two disconnected networks half the size; won’t bore anyone with an explanation of that.

Sydney’s “Metro” trains have the same track gauge, the same loading gauge, the same platform height and run off the same voltage as the rest of the fleet. That allows more of the existing lines to be, over time, converted to driverless operation.

Any new rail vehicles in Auckland may be driverless and/or designed for street running and/or able to take sharper curves and climb and descend steeper hills than the existing rail fleet. But the new rail vehicles should IMO have the same gauge, the same loading gauge, the same platform height and the ability to run off the same voltage (may require dual voltage) as the rest of the Auckland fleet.

There are no significant disbenefits to such compatibility but the benefits over time would range from modest e.g. joint maintenance facilities, to very, very significant e.g. tram-trains running on the mainlines outside the CBD to make use of the significant redundant capacity the network will still have, other than in the CRL, and then on-street in the CBD along Quay Street as the CRL will be full. There are many other ways that a rail fleet with significant interoperability would and could benefit Auckland over time. As we don’t know what the future holds it is surely responsible practice to provide future generations with as many options as we possibly can with the decisions we make today.

PS: a second underground transit route through the CBD would cost at least what the CRL is costing.

Constraining new rail lines to the standards of the existing heavy rail network would be a mistake.

Keeping the same loading gauge and platform height will make future rail stations worse. The high platform height will make all future platforms more expensive, and in particular will make on street running less practical. The large loading gauge will force the continuation of the relatively big gap between trains and platforms, which will require retractable ramps that slow dwell times at stations.

Keeping the same 25kV AC traction system is no problem for any new completely grade separated rail line. However it would be a hindrance to on street running lines where battery or wireless systems could be used instead.

Of course a second underground transit route through the CBD will cost more than the CRL. However the cost will be even more if constrained by legacy standards. In particular the need to accommodate physically taller trains (higher platform height and traction wire height) will force the tunnel(s) and stations to be larger, which is obviously more expensive.

Something you haven’t mentioned is signaling. Rail signaling integration is complicated, difficult and expensive. Crossrail in London is trying to connect to the legacy rail network (with 3 separate signaling systems) and this has lead to more than 2 years of delays so far. If Auckland builds a new rail line from scratch then trying to make its signaling compatible with the existing network is high risk and probably not worth the effort.

What Auckland’s public transport network needs is greater geographical reach. The areas with unmet PT needs are the ones without rapid transit coverage. The ability of new lines to share legacy rail infrastructure will be of no use since there is no legacy rail infrastructure to share in those areas. The ability of new lines to be retrofitted into road dominated environments (North, Northwest and East Auckland) will be the priority.

Completely correct Bear.

Auckland’s current rail system is already overloaded with too many tasks: Metro, Freight, Intercity, on a tiny two track interlined network riddled with level crossings, creaking formations, and constrained corridors (but soon new rail). Oh and signals need major upgrade to squeeze more capacity too. Negative redundancy. We will keep improving it, at considerable cost, but certainly won’t be adding new Metro branches, that would be very high cost/low value.

Nor is there any value in having new rapid transit system carry any particulars of the old colonial rail system over, why would it? Nostalgia?

Transit systems connect by transfer not junction, this has so many advantages as it massively increases; frequency, capacity, reliability, redundancy, stageability, safety, cost, and so on.

The user doesn’t care about gauge, bogies, loading gauge, etc, and all the other technicalities. But they do care enormously about frequency, reliability, safety, system reach, comfort, modernity, legibility.

Vehicle interoperability is of very little value. No train London’s Northern line, for example, runs on the Jubilee line, or the Central line, or the Bakerloo line. The Elizabeth Line is on the Tube map, users hop from one to the other without caring that those trains can’t (or, even where technically possible, won’t) switch lines themselves.

The new Sydney Light Rail system crosses the old one, but they are not interoperable. They run completely separately. Passengers’ legs are the interoperability component.

The idea of transit networks being like freight or intercity ones where there is value and utility in standardised vehicles being able to access the whole network is a mistaken one. Is simple mainline thinking not urban transit thinking.

Unfortunately this also aligns with road network thinking too, which of course dominates our transport practice and experience, so it seems like ‘common sense’ to the average driver too. They are wrong.

I feel that rails that have potential to serve wider regions be HR. Lines that will always be within urban limits be LR. I could see a HR line extend from Kaukapakapa to Silverdale, then proceed on to Auckland via the second harbour crossing. This line could draw developers away from the fertile soils of Pukekohe, where no housing developments should be going on. Such a line could then be extended to Kaipara Flats and into the Warkworth area. In the future commuters could potentially live on the Hibiscus Coast and commute to both Auckland or Whangarei. The airport line should be in from Onehunga and out via Wiri and be able to serve distant regions. LR would be good for the NW motorway, Westgate to Glenfield, Westgate to Huapai could connect with the HR system, the Auckland Isthmus roads of Dominion, Mt Eden, Sandringham and extending through Remuera Rd to Eastern suburbs, with direct lines to St Heliers and Kohimarama, perhaps continuing to Panmure. The main HR routes need to be (and can be) widened for 3 or 4 mainlines to cope with express suburban, long distance passenger and freight services.

Your general idea of how to balance HR and LR is worth considering.

But we’d be better off neither building on the fertile soils of Pukekohe nor any other ‘distant regions’. Because

1/ regardless of the rail type you might provide, the driving modeshare of residents in new sprawl households is still too high;

2/ those households put in instead as TOD improves the travel options and local amenity – and reduces the vkt – of residents in existing urban areas.

For too long this has been claimed to be too hard, but it’s not. It’s just about setting the right policies, stopping the wasteful spend of billions of dollars on greenfields sprawl infrastructure, and using that money instead to enable this TOD.

I agree to a point Heidi. The pepper pot sprinkling of housing across greenfields as per Pokeno and Paerata currently, is wasteful and disorganised, but properly designed sattelite villages with a combination of 3 or 4 storey apartments, terrace houses, semi-detached and stand alone housing with areas for parks and wetlands, areas for amenities and green belts between villages would offer a quality standard of living in a sustainable way. Vkts could be discouraged through congestion at peak times and with a good PT service outside that time. I just don’t think that many NZer’s want to be crammed into one big city. I do agree that we can densify a bit more, but there is a limit, at which point quality of life reduces. When that happens, there needs to be a damn good alternative. Currently, people are following a world trend to keep close to the coast, so from Orewa to Leigh people will continue to buy and build. We need to be able to offer them some rapid PT, and stepping the population out in a planned way will help to provide this when needed, which won’t be long from now.

But allowing people to keep sprawling and having to offer them rapid PT takes too much money; if that was costed into their lifestyle decision, they wouldn’t choose it. It’s money that should be spent on providing a proper network in the urban area we’ve already built, where it can be split between the many, not the few, in an affordable way.

Why would you think we’re anywhere near a density point beyond which quality of life reduces? Our quality of life is limited by our car dependence and all the pollution, danger, noise, lack of walkability and carbon mitigation costs it imposes on us. We have the opportunity to intensify well and completely change our urban form – IF we harness it.

If we don’t, all we do is continue to ruin ecosystems and induce traffic.

“If we harness it”. From my point of view, Auckland citizen’s quality of life is already below what it was 20 years ago, due to crowding. I agree that Auckland should not develop beyond Drury in the south, Clevedon and Whitford in the east, the foot of the Waitakeres in the west and Long Bay in the North. We do need to densify within this area. But we have Pukekohe, Tuakau and now Pokeno in the south, Beachlands and Maraetai in the east (not to mention Waiheke Is) and Whangaporoa, Orewa and Warkworth and the Mahurangi Beach towns in the north and Piha and Whatapu in the west. All of these areas need better planning too. They need a variety of high rises and terraced housing as well. The problem is primarily one of human nature. Few people choose to live in densley populated cities. They are there primarily for employment. I agree that the city needs to be well planned so that life is easier and more bearable and that nature doesn’t suffer, but I also believe that many people will (and do) provide a market for out of town commuting, and I believe that this will be very hard to deter. In fact, most politicians won’t! As it is, property developers have all the say, once the land is freed up by councils. That is why we are currently building on the most fertile soil in the country around Pukekohe and every house has a section. I would see more hope in directing councils to move the developers to the less fertile soils (clay) of the north and northwest. However, I would also urge that councils are more prescriptive with the land use, dictating, areas for housing, amenities, schools and the like, types of housing (level of density) and maintaining wildlife refuges, especially wetlands in the northwest. If the cost of this is an expensive rapid rail service, then so be it. We have to be able to find the balance between living sustainably with nature, having a quality of life and being able to deal with human behaviour to make this happen. Harnessing that behaviour at the city limits will be difficult and will ignore the inevitable overflows which also need to be a part of the “harnessing”.