The Covid-19 lockdown showed us all how important housing quality is. Some homes were uncomfortable or got cold. Some homes were fine physically, but not well suited for how they were used over lockdown. For me – a numbers-focused economist type guy – it’s a crucial reminder that it’s not just about the quantity of our housing and whether we’re building enough. It’s whether our homes (existing and new) are good enough, and whether they’re well suited to our needs: needs that can change over time, and sometimes in ways we don’t expect.

Housing quality is starting to get some long-overdue policy attention. Stats NZ define it as

“The degree to which housing provides a healthy, safe, secure, sustainable, and resilient environment for individuals, families, and whānau to live in and to participate within their kāinga, natural environment, and communities”.

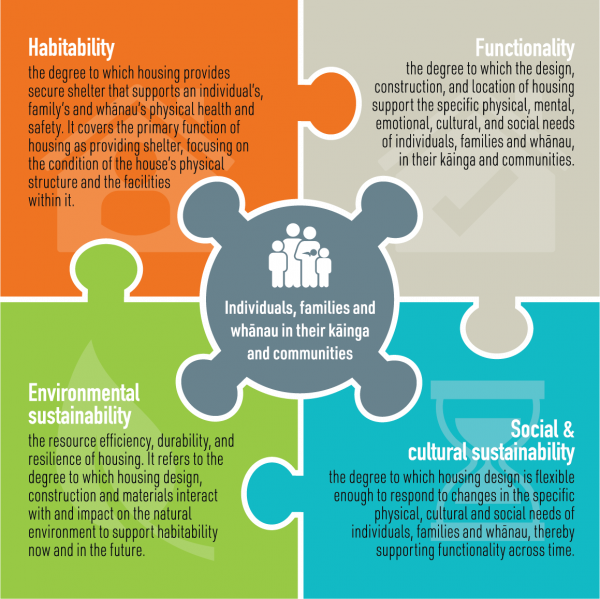

Stats NZ published a Framework for Housing Quality last year, which looks at four interrelated elements of housing quality:

The top two elements focus on the ‘here and now’ whereas the bottom two recognise that housing is long-term, and has to meet people’s needs both now and into the future.

Habitability is the most obvious dimension; is the home physically fit to be lived in? Is it built solidly (structurally sound, ideally not earthquake prone, offering protection from wind and rain); is it secure (lockable, the occupants can feel safe that others can’t get in); is it healthy (offering water, light and energy sources, ways to clean yourself and prepare food, etc).

Our homes often underperform on the ‘healthy’ aspect. The home should offer “protection from cold, dampness and mould, indoor pollutants, and excess heat” and too many NZ homes don’t meet the mark. More on that below!

Functionality gets a bit broader, and different households have different needs. The home needs to meet the functional requirements of its residents, as well as the people who might visit. This could mean accessibility for people with disabilities; a place to practise religion or host friends and family, etc. Maybe it means a ‘home office’ space – but is this just a way for landlords to sneak an extra bedroom in and collect more rent on a space that wasn’t designed to be lived in?

Functionality includes several aspects that relate to transport:

- Social and economic participation: enabling “access to social support networks and interaction within the local community”, and “access to employment”)

- Connectivity: enabling “access to transport, services, and the environment, including health services, education, employment, food sources, green spaces such as parks, and blue spaces such as beaches”

Environmental sustainability Stats NZ talk about this as meaning ‘habitability into the future’, but it’s really a whole-of-life look at the home. Was it designed and built with sustainability in mind; can it be lived in sustainably (i.e. energy and water efficiency, ‘solar gain’ and consideration of heat and shade); and are the materials are durable so they will last into the future?

Social and cultural sustainability Stats NZ talk about this as meaning ‘functionality into the future’. It’s whether the home can be easily adapted to different needs – e.g. the same residents as they get older (can it be made safe for people with limited mobility or vision?) or different residents who might look for different functional elements.

Stats NZ note that a home’s location “is an important part of all four elements but may interact with them in different ways”. It can affect habitability as “proximity to busy roads and exposure to heavy traffic can result in exposure to noise, stress, and pollutants”. It affects all the other elements too:

Location can also affect people’s ability to access services, employment, and green spaces. Whether an area has easy access to public transport, cycleways, and walkways can be important in terms of both environmental sustainability (potential reduction of carbon emissions) and social and cultural sustainability (meaning that people are less reliant on private cars for transport).

Now there’s a framework for thinking about these things, Stats NZ and other agencies (including MHUD, apparently) can start to collect data. This has already begun:

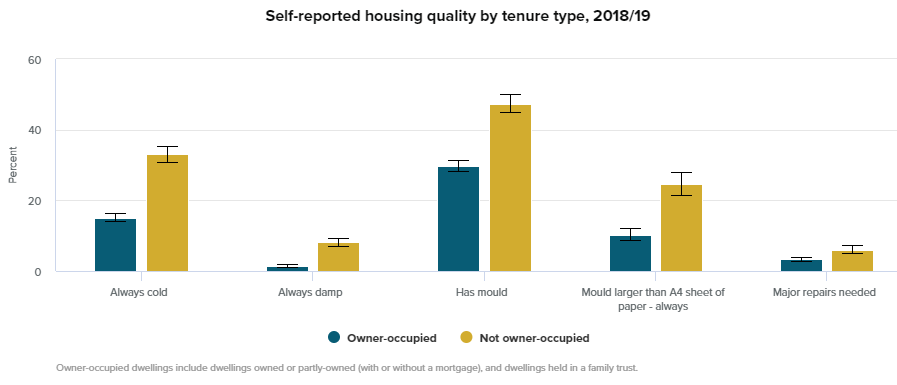

- The 2018 General Social Survey found that nine out of ten NZers were satisfied (or very satisfied) with their home, but satisfaction was lower for renters.

- The same survey found that a third of homes were too cold in winter (almost certainly an underestimate, since temperatures were measured during the daytime in the part of the house most likely to be heated), and too warm in summer.

- The 2018 census asked a couple of questions on housing quality, including whether the home never/ sometimes/ always had mould, or was damp.The census found that 22% of homes were damp at least some of the time, rising to 38% for rented homes. The figures for mould were similar, and again renters came off worse.

Where to from here?

I want to write more about housing quality this year, as it certainly seems like one of the ‘less examined’ areas of our homes. The Framework is a good first step, but what will actually be measured? What is the role of the market, and government, in achieving better quality?

I’d like better information to be available for both buyers and renters – there’s a lot of potential for ‘information asymmetry’ when moving house, and it’s hard to know what you’re getting into. Who will be a trusted source of information (spoiler: probably not the real estate agent)?

Should the government (or councils) tighten up regulation, and if so what areas should they target? Their current focus is on habitability, but some aspects of functionality are covered too – e.g. the Unitary Plan has minimum living space requirements. If they broaden their focus too far, will they run into tradeoffs – quality vs cost, present vs future, or pre-empting people’s choices about how they want to live?

Should the government (or councils) fund quality improvements for existing homes? If so, should they subsidise people to renovate their kitchens as Australia is doing, or is there a public policy rationale for focusing on certain upgrades and household types (spoiler: yes)?

I’d love to hear from you in the comments below – how can New Zealand get to a future of better-quality housing?

Processing...

Processing...

This is such an important issue John. How to encourage really good housing at development stage and raise expectations in residents on what to look for and demand? Do we need a Grand Designs TV show looking at the wider functionality of housing? Water resilience is on my mind too.

Good to see discussion on the diverse attributes of housing quality. It is widely understood our housing, even many new homes to the legal minimum of the Code, are much lower quality than most of the rest of the world. “Made for NZ conditions…” yeah, nah.

The actions we take based on this framework are what matter. Learnings from elsewhere:

– higher regulatory standards are a necessary tool. The govt says it is improving the Code; right now it really isn’t. This has to change to address climate change, population health, energy costs.

– govt leading by example is really valuable in changing the market. Kainga Ora adopting Homestar is a huge step forward which will drive change in supply chains and building practice.

– retrofit is a huge opportunity that we are currently neglecting. Ceiling and floor insulation is good, but woefully inadequate as an overall package. Govt needs to incentivise this area, remove regulatory barriers, stimulate skills training and business growth, and adopt clear standards for measuring outcomes (for example, passivhaus enerPHIT or Beacon Pathway’s retrofit standards).

The sad fact is that we have actually had studies and analysis of housing quality for years now, thanks to people like Phillipa Howden-Chapman and many other great academics and advocates.

We just haven’t done much about it.

How can you say we need higher regulatory standards then say we need to remove regulatory barriers?

And you must have really good knowledge of the code to know how it relates to international codes?

Better standards and less barriers are two different things. We have the worst of all worlds – low standards and complicated process with high costs. I’ve designed, consented and administered but of contracts in multiple jurisdictions and NZ has to be the least efficient and effective.

but of contracts = build contracts…

Yes horribly inefficient and ineffective. But I don’t agree that our standards are low. If you consider our cost to income they’re too high.

Thanks, John. I looked up what’s covered by the framework in terms of covering the site with low-rise sprawl, as infill tends to do, with driveways and turning areas. Also as many of the smaller developments (eg 4 or 10 homes) are doing even in the THAB zones. Very little permeable land left, and unnecessarily so. It could have been a bit more overt, but it does seem to include this aspect, so I hope this framework is one way to address the flooding problem the consented developments are creating:

Environmental sustainability includes …

Responsiveness to climate and environment [which] is how responsive the building envelope is to the climate (different weather events). This includes the efficiency of energy and water use, the limited use of finite resources…

Facilitation of sustainable living [which] is the ability of people to live sustainably within the home and within their community. This includes factors such as… the sustained health of neighbouring ecosystems.

Other considerations of environmental sustainability [include] … their resilience to climate change, and the resilience of the housing site…

Thank John for this post, I looked at min dwell size – link below, interested to know what you are think.

What is missing from the conversation is the importance of having the front door opening onto a public foot path. Jane Jacob writes about the problems of front door open lobbies or private hall ways and with Covid-19 we have seen how unhealth ships can be and rest homes. My mother was lucky her front door open to public space, some of her older friends not so lucky their front door open to an internal corridor, life was like living on a cruise ship for them.

http://hamiltonurbanblog.co.nz/2019/03/dwelling-minimum-size/

Hi Peter, interesting post on minimum sizes – thanks! Personally, I’d be happy to see those regulations tightened. In my life, I’ve lived in:

1) A student hall of residence for a year – my bedroom was probably 12 sqm tops, but I didn’t spend much time in it. We had a little communal lounge on our floor but spent most of our time elsewhere, in the dining hall, on campus or in any of a number of bars.

2) A 53 sqm, 2-brm apartment with a small balcony and breezeway access. It was fine for me and my then-girlfriend, and no doubt it could have fit more people in if required – although probably not in a level 4 working-from-home lockdown! Anyway we were only there for 6 months before being booted out so the landlord could move back in – I think it was him, his wife and possibly one kid.

3) From there to a 62 sqm 1-brm apartment in the same complex, with an outdoor courtyard and corridor access. This was a nice step up but the rent was about the same, since the reality is that people will usually pay more for a 2-brm regardless of size. We were there for almost 5 years.

A crucial point, also made by the commenter on your post, is that it’s not just about the size of the dwelling; it’s about what facilities or public amenities are nearby, and how the dwelling will actually be used by the occupants.

However, a really small home inevitably does have limited functionality – or adaptability – in itself. So it probably comes off poorly on that element of quality. But should we regulate that? Again, I think context is important, and resource cost too; if households are getting smaller and we can deliver several small homes for the cost of one large one, then why not? It illustrates the tradeoffs we’ll run into though.

In NZ houses are generally built to the building code, ie built to the minimum possible standard. The only way to improve the standard of building is to raise the minimum standard.

Opportunities for improvement include:

– Increase insulation requirements. Lots of new homes already do this because it’s such a cheap way of making the house more comfortable and very difficult to do retrospectively in modern houses without underfloor cavities or ceiling spaces.

– Introduce an air-tightness standard. The technology is now readily available to test how air-tight buildings are. A lot of the benefits of insulation are lost if the house has too many air leaks.

– Mandate forced air ventilation with energy recovery (ERV/HRV systems). A lot of overseas jurisdictions already do this so the equipment is inexpensive and readily available. This works in conjunction with a relatively air-tight house to maintain indoor air quality.

– Mandate grey water recycling (using wastewater from the shower and sink to fill the toilet cistern). This is a very easy way to cutdown water usage over the life of the house but it needs to be plumbed in and is very difficult to retrofit.

– Increase the energy efficiency standard for hot water heating. A big portion of an average house’s electricity usage is hot water heating and this is one of the easiest to minimise. This could achieved be by using a solar panel system in conjunction with a traditional hot water cylinder or by using a heat pump hot water cylinder.

Another issue with NZ houses is construction cost. Improving the building code as I’ve described will put upwards pressure on construction costs (but not hugely so). The easiest way of building a house cheaper is to build a smaller house, this also reduces its environmental footprint. We need to look at getting rid of the barriers to doing this whether they be developers covenants mandating minimum floor areas or planning rules restricting density.

I’m pretty sure that a lot of the problem in NZ is that the houses built between 1990-2010 weren’t built to code because the builders could get away with it.

One thing I’ve long said is that it makes no sense for all of NZ to have one universal code. Every winter in The Southern South Island and Central North Island sees a considerable dumping of snow yet it virtually never snows north of Cambridge nor in Wellington. It’s clearly considerably more humid on the western side of NZ and north of the Bombay hills than it is on the eastern side of NZ.

So why is it that buildings across the nation are built to the same standards?

I recall a few years ago; a recently-built sports gym in Invercargill’s flat roof collapsing from the weight of the snow. From what I understand; this gym was designed in Australia by an Australian architect. Why don’t the building regulations in Southland, with respect to the snowfall that occurs every winter, completely prohibit flat rooves?

Not really universal in terms of geography relating to insulation requirements, see:

https://www.building.govt.nz/building-code-compliance/h-energy-efficiency/h1-energy-efficiency/building-code-requirements-for-house-insulation/house-insulation-requirements/

As in Central North Island is the same as the South Island, still pretty much bare minimum though.

‘ Improving the building code as I’ve described will put upwards pressure on construction costs (but not hugely so).’

Ya reckon? I think you’ve added a good %20 to the already far too high cost to build a house.

And why can’t I if I decide to, build a rough shack to live in if I want to? Why do I have to go begging to the council for permission to build a house to a code someone has dreamt up so any future buyers ‘investment’ is protected?

Some have talked about the ’right to decent housing’ but we don’t even have right to build.

I agree. The worst part about the building code is that it encourages a whole heap of expensive paperwork and experts which means builders cheap out on the stuff that would actually make houses better. It also encourages building big expensive houses; if you have to spend a ton of money on surveyors and geotech reports and architects and engineers just to build a basic residential house you may as well make it worthwhile.

Yet we have houses built over a hundred years ago that are fine because they spent the money on good materials and good builders, not on reports and paperwork.

I agree that you (as an adult giving informed consent) should have the right to build whatever rough shack you like and live in it. However this will inevitably lead to people who don’t know any better or don’t have any influence (your children, your elderly parents, your tenants etc.) being forced to live in the same rough shack that you build. So I don’t think the concept really scales to the country as a whole.

Thing is LB were are doing exactly that. We just call them caravans and tow them into a back yard.

It’s already at the point where many can’t afford the current code and the hopeless application of by the council so I get a bit annoyed when people claim the the code needs strengthening.

Jumbo you must had recent experience with the ‘system’. My condolences ha. What really pisses my off is when their box ticking system can’t find a box to tick they demand a Producer Statement and you have to cough up another $1000 to cover the councils arse when they’ve already charged you thousands to check there isn’t a box to tick.

The whole system from top to bottom is broken and we will never have affordable housing till it goes.

Auckland Council wants a producer statement for absolutely everything. You have to have a “professional” (18 year old boy who is (not) being “supervised” by an LBP) to do everything, even painting on a simple bathroom waterproof. I don’t think these make the quality better at all, they just save the council’s arse and cost us lots of money. In fact they barely inspected anything other than paperwork during inspections. No check of roof or cladding or anything – I wonder how we got leaking homes?

I’d like to see the council out of the process altogether. Their job should be planning compliance and record keeping only. There’s no point in having them involved when they’re demanding producer statements for everything anyway.

If we put engineers or specifically qualified project supervisors in charge of the building process we might get some actual value for money.

Government should be in charge of building consents, not councils. Government sets the building code, governments should enforce it.

The houses we live in also reflect how we consume energy. Most of the older homes in NZ were built to have a fireplace, coal stove or electric heaters on all day in winter. Dampness wasn’t so much of an issue as one adult would be at home labouring on keeping the home functioning and they (almost always she) could open the windows in the mornings to air the place out. Society changed but those houses are still there, partially insulated and without ventilation other than the draughts.

The housing stock was designed around cheap fuel or cheap power. When Max Bradford decided energy was a market rather than a necessity people stopped heating them and stopped opening the windows as often. Only the Greens have even tried to fix this, but they didn’t do it very well.

I agree with you on the reasons for our house design historically.

However, I think you are drawing a long bow to suggest a significant number of people stopped heating their houses after Bradford’s reforms, a few would have sure but not large numbers.

Even if you are correct it just demonstrates the benefit of charging true costs for power. By treating it as a cheap necessity just discouraged people from improving their houses to reduce resource consumption.

Bradford’s “reforms” were an unmitigated disaster.

Total reliance on ‘market forces’ = total market failure.

Very informative opinion piece btw.

Agree, if we didn’t have Max Bradfords “reforms” power would be a lot cheaper in this country, we’d likely have a much higher percentage of renewables and we would have more reliable power as it would be used as best purpose rather than most profitable (eg saving hydro during dry years as much as possible rather than having some spill while others are low).

Price definitely has an impact on power usage. I don’t know many people that aren’t careful with their power usage especially regarding heating due to powerbill costs.

Yip. And I’d put $100 on it being cheaper to subsidise power so everybody can access it cheaply than it is to run people through the health system cause they’re cold and damp.

Or can’t afford decent food cause of the power bill.

Such a cruel thing to do.

Tis I – agree. However, it would be cheaper again to channel the money towards home insulation, then the cheaper power wouldn’t be leaking straight out of older houses.

Reducing the cost of power just encourages more wastage, which means more infrastructure has to be built to generate and transmit the power.

Jezza weren’t people using highly subsidised power to mine bitcoin in Venezuela? Classic example of subsidy gone wrong.

The ‘market’ model used by Bradford was based on the flawed concept that every dollar is equal. Economics is supposed to be about maximising utility not the traded dollar value of a good. If you wanted to maximise the utility of energy then we would have large subsidies for the energy poor to enable them to heat their home, dry their home and travel to where they can make enough to support themselves. Instead we have a cash market system where many participants are priced out and energy gets allocated to those with the highest incomes rather than those who can gain the most utility from using the resource. But that is what you get we wealthy people make the rules.

Another issue is that a lot of housing in NZ was copied-and-pasted from Australia.

And aside from a few geographic locations in the South of Victoria and Tasmania (where the buildings are more like British buildings anyway); Australia has a completely different and warmer climate than NZ and were designed more to keep people cool than to keep them warm and dry.

One of the best things this government is doing is building more apartments near the CBD and stations. It gives people choices. The Unitary plan has helped. This will reduce travelling time for the occupants and allows them to better enjoy the benefits of being close to work, community, culture and sporting events.

Urban sprawl is costly. Those developments in distant suburbs require expensive earthworks, roads, footpaths, services all costing about $160 000 per section. Sprawl adds to congestion and takes good farmland.

Then those suburbs are infrastructure poor and have less libraries, cultural and community groups. I doubt many living in the new area of Flat Bush would be going to the rugby at Eden Park. It would take 2 hours each way to attend.

A family living in such a suburb would require 2 or 3 cars and each of the members would be commuting hours each day and transport costs and wasted time would be a burden keeping them poor.

For Auckland to be competitive housing is high on the list. Any student, local or international, commuting 2 or 3 hours each day will struggle with their studies. Any person living in a good apartment in the city will be more contented if they also work in one of our many good CBD located businesses

I’m not against more of a shift away from detached houses towards medium-rise multistoried residences, at least concentrated near town centres and transport nodes by any means.

But I was pretty disappointed when seeing renderings in the Unitec plan in the article from a couple of days ago, where the said residences were drawn as the sort of bland & uninspiring, glass-exterior, minimalist rectangular blocks that the rest of the world learned are a bad idea with bitter experience.

Can’t NZ ever get anything related to urban design right?

The rest of the world has actually learned that minimalist buildings with a lot of glass are fantastic residential buildings. Which is why across most of Europe, including the UK, this is what every apartment building currently going up looks like. You see exactly the same architecture across the UK,the low countries, the Scandinavian capital cities, the meditteranean cities, across the alps.

Thankfully architects have finally learned that lots of sunlight is great and lots of glass is attractive.

While the point you made on that post about builkding around parks, not building in parks was great, the point about not building simple structures that give good daylight access was terrible.

In 2009 (our last recession) there was a really effective home insulation scheme as a result of agreement between the Greens and National. Seems like we should be doing something similar again, but even bigger?

Some of that is being done https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PA2005/S00124/more-warmer-kiwi-homes.htm and it’s better targeted than last time, focusing on low-income renters (the old scheme was mainly taken up by homeowners). I’ll take a closer look at this in future!

By better targeted you mean by focusing on rich landlords that have just made a ton of capital gain without paying a cent in tax? Or do the low-income renters get to keep the insulation if they leave?

Lord help us…

Hmm, on closer look it seems the new scheme focuses on low-income homeowners only, not renters. Which probably stops short of where I’d like.

To answer your question Jimbo – I would want the scheme to focus on the people who need it most and are least likely to be able to afford it themselves. That will generally mean people who are low-income, and they are generally more likely to rent. As with the graph in the post above, renters are more likely to live in damp, cold homes and landlords may not have the financial incentive to improve them.

We can address that either with tighter regulation (as has been done recently) or with incentives, the stick or the carrot.

I haven’t dug into this in detail yet so will save it for a future post!

Definitely the stick in this case. I don’t want to pay for landlords to enjoy more carrots.

Isn’t it kind of like the govt paying the supermarket to not put poison in the food?

We already gives landlords the carrot of tax free capital gains. Until they give that up they don’t need anymore carrots; onlyy sticks.

We rented a villa to four students who all had community services cards. As a result we got the ceiling and underfloor insulation put in with a huge subsidy under the old scheme. It really did make a difference for them. But no they didn’t get to take the insulation with them. They probably didn’t want it as one is a marine biologist, one is a taxation lawyer and one is in marketing now. They all probably live somewhere much nicer now.

If someone gave me $25K with the stipulation I had to spend it on improving my house then underfloor insulation and solar would be a no brainer. Possibly also an external socket for charging an EV?

The graph highlights that the government should get as many people into home ownership as possible, as clearly owning your own home results in it being of being quality.

It used to be that home ownership was guaranteed in New Zealand. We need to return to that.

The property that the landlords own is the landlord’s “own home” that they own too.

So clearly not.

Note the distinct concept of ‘home’ as a place to live – and the right to quiet enjoyment of it whether you own or rent it.

It’s certainly possible to have a rental sector that consists of good quality housing. Other countries manage it, why not NZ?

Agreed, why not?

Contributing factors include:

– Other countries have higher building standards, both by stricter building codes and more capable residential construction sectors.

– In countries with better standards of rental housing, the housing is typically owned by institutional investors (who want a low but reliable rate of return over very long time horizons) rather than here in NZ where it’s typically owned by mum and dad investors (who think much more short term in their investing).