With the country now at Level 1 and ‘back to normal’ it means all of the restrictions have now lifted. That means that many more people will soon be heading back to the office. Universities will likely take a little longer and not be back till the start of the next semester.

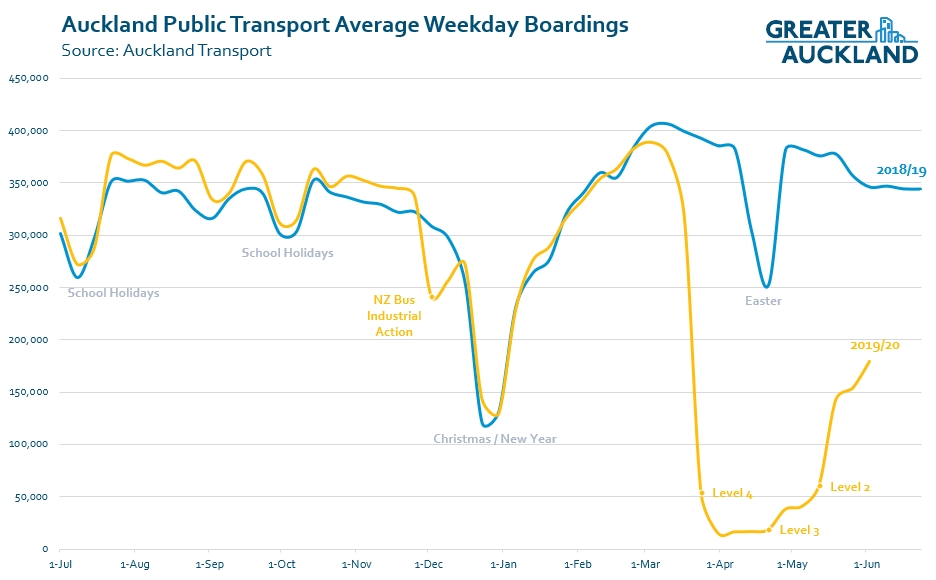

As I wrote last week, the big question now is how long it will take for public transport demand to get back to some semblance of normalcy. Given the trends we’ve seen so far, I’m fairly optimistic this will happen relatively quickly. For example last week the four working days saw an average of 179k boardings a day. That’s about 52% of what usage was at the same time last year and is up from about 154k trips the week before. It’s also not too bad when you consider that physical distancing requirements had reduced capacity by about 50%.

But a return to normalcy also means we need Auckland Transport to get back to focusing on how to get a lot more people to use public transport more often. Doing so is needed to play an important contribution in reducing emissions and improving urban mobility.

To get more people using PT there are many things we need to do. These range from small improvements and tweaks to improve the customer experience to fare policy to large infrastructure projects to improve the network.

Many of those large infrastructure projects are already underway and in the past, particularly around the time when Auckland Transport raise fares, we’ve often seen debates about fare policy, including the suggestion of free fares.

An interesting paper from the Council’s Economist Unit released in April looks at question of whether a better network or free fares would deliver better climate change outcomes.

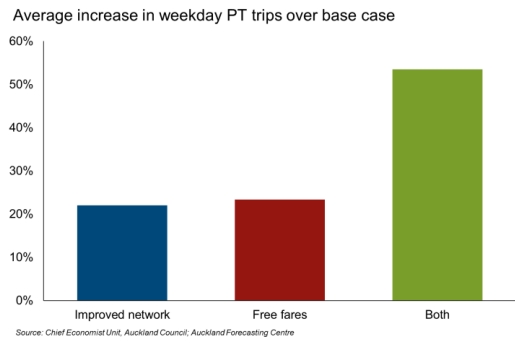

To test the impact of large interventions we worked with the Auckland Forecasting Centre to model a range of scenarios that allow us to see the impact April 2020 of i) planned and proposed infrastructure improvements to the network ii) more radical fare policy changes, and iii) a combination of the two. In all cases, the counterfactual is that no changes are made to either today’s PT infrastructure or policy.

It’s worth noting that this is a model – it won’t be a perfect reflection of reality – but is a reasonable guide for the scale of likely impacts.

For the network improvement option, they include the City Rail Link, the Eastern Busway, more bus lanes around the city and Light Rail to the airport and to Westgate. This largely sounds like the network that is expected to be delivered as part of the current ATAP.

What I find strange about this scenario is that they estimate ridership would only increase by 22% over what would occur without them. It’s not clear what timeframe this analysis covers but it doesn’t really pass the sniff test. There were just over 103 million boardings on the network in the 12-months to the end of February and growth had been slowing – you can see on the graph that this year prior to COVID ridership had largely been tracking last year.

The City Rail Link alone is expected to roughly double usage of the rail network within a few years of opening to around from 22 million to 50 million trips. That alone could potentially deliver the 22% increase but add in those other projects and if we only achieved a 22% growth, that would be a significant underachievement. Also of note, ATAP suggests usage will rise to 170 million by 2028, about an 83% increase on what it was in 2018.

By comparison, if instead of improving the network, we made fares free, the model suggests we’d seen an increase of 23% in ridership. The problem with this option is there simply wouldn’t be the capacity on existing services to accommodate that kind of increase unless it all occurred off-peak. While fares will play a part for some, for most PT is simply slower and less convinent and so addressing that is key. This means network improvements, like those above, would need to be made.

Doing both network improvements and free fares is expected to deliver a 54% increase in ridership.

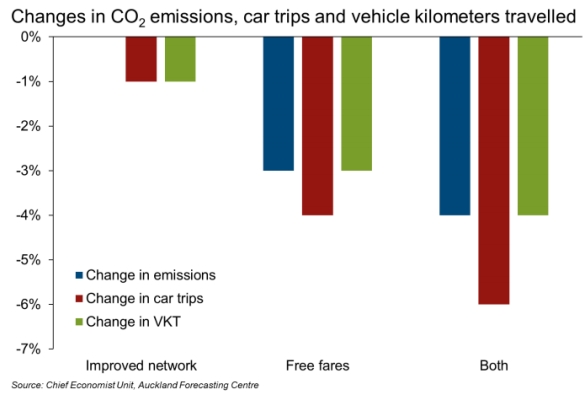

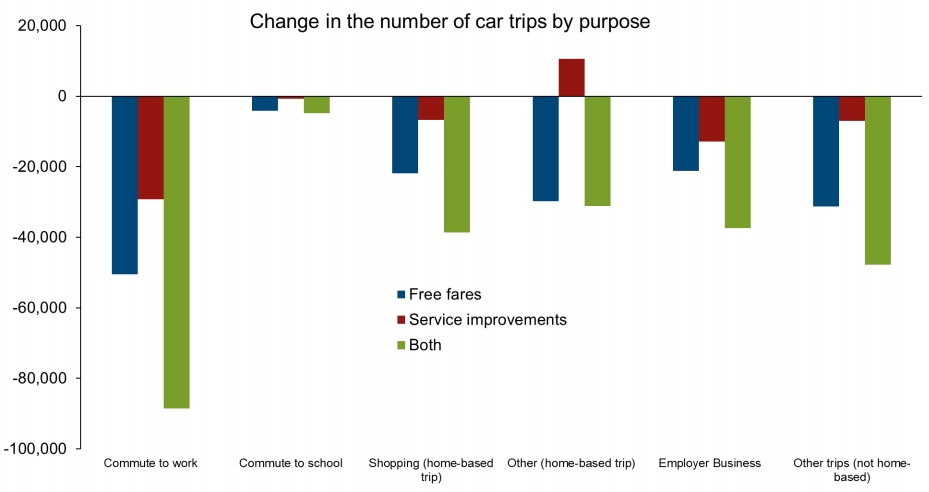

Translating these changes to changes in emissions and car trips they estimate:

- the improved PT network would only reduce car trips by about 1.2% but have almost no impact on emissions as the gains would be swallowed by induced demand.

- free fares would have a greater impact with a 4% reduction in car trips and a 3% in emissions.

- both options combined see car trips drop by 6% with about a 4% drop in emissions.

They don’t explain why, under their model, similar amounts of increased ridership generates quite different levels of car use and emissions. I also suspect these outcomes will be heavily skewed by the earlier issue on the impact on usage but th

After putting some high-level costs and benefits around the the free fares proposal they note.

These scenarios reveal a few things that can help inform the conversation on good transport policy. At a high level, we learn that emissions reductions alone are unable to justify a policy as radical as free PT, with a value of the reduction in the tens of millions of dollars per year but a likely cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

This does not imply that reducing emissions is a bad thing, but rather points out that emissions cannot make the case for free fares on their own. Naturally, there are other important reasons to consider making PT free – congestion, social equity, better access to jobs, and a nudge toward sustainable transport – but as always, the value of these impacts needs to be weighed against the costs.

We also learn that PT users respond to both changes in service quality and changes in fares. Put simply, this is because fares are not the only or even necessarily the dominant cost in someone’s decision to use the service. The other costs of travelling are largely time costs – waiting, delays, transfers, headways, and total in-vehicle travel time – costs that an improved network can lower. The modelled results suggest that fare reductions and the service quality improvements we looked at are equally important to PT users.

It is important in all this thinking to remember that “bums on seats” is not the goal. PT is a means to achieving the other outcomes we have highlighted. One further implication of the analysis is that improved PT itself won’t eliminate congestion and emissions. Something that cuts more to the behaviour of motorists, such as congestion charging, is still likely to be needed.

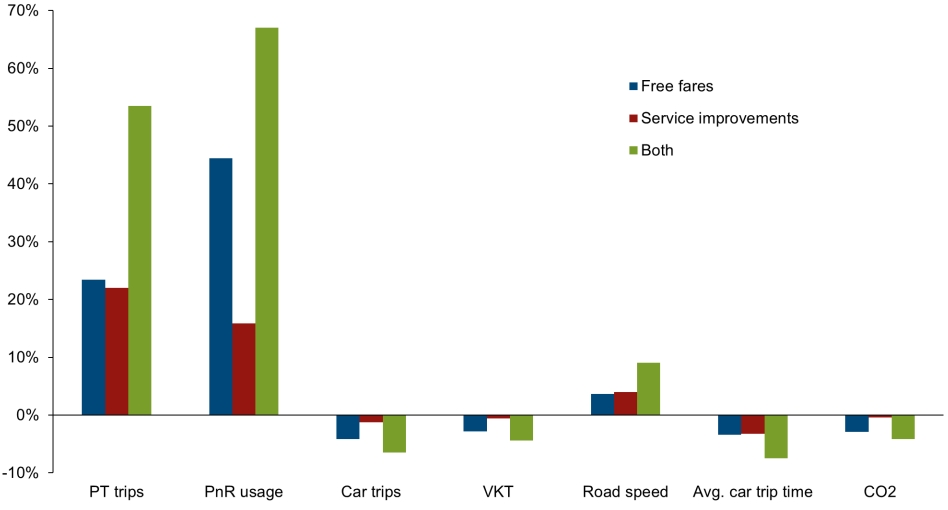

A separate presentation I was provided breaks down the impacts across a number of other metrics

And the change based on the type of trip

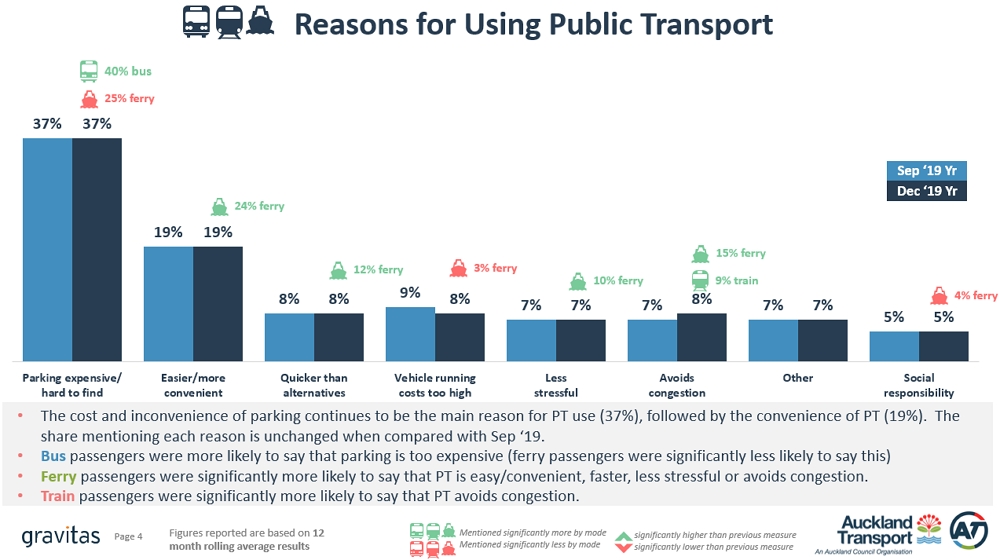

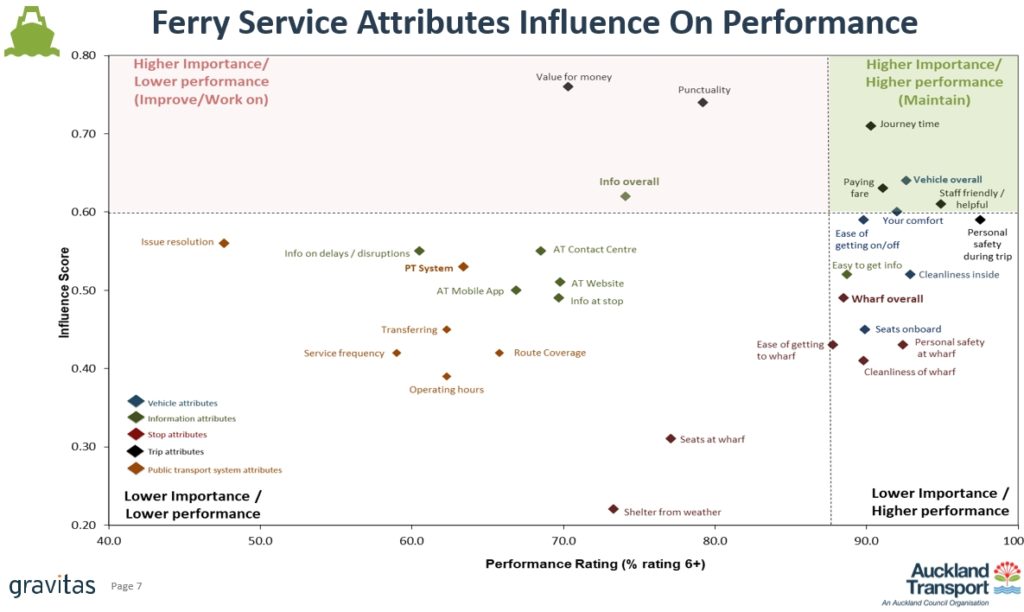

Overall it is an interesting report but there does seem to be some flaws with it. Furthermore, it doesn’t line up with other research we’ve seen that suggests frequency, reliability and speed are larger drivers of PT us than price. I even recall seeing a chart showing this from Auckland Transport a few years ago but have never been able to find it since. They did send me the results of a a survey in December of nearly 13k customers though showing the drivers for current PT users.

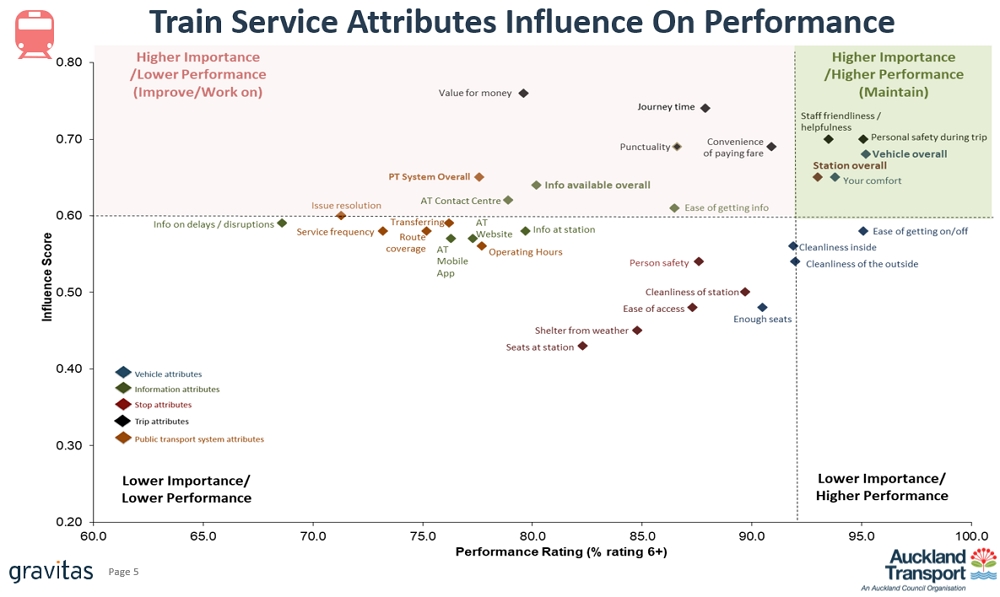

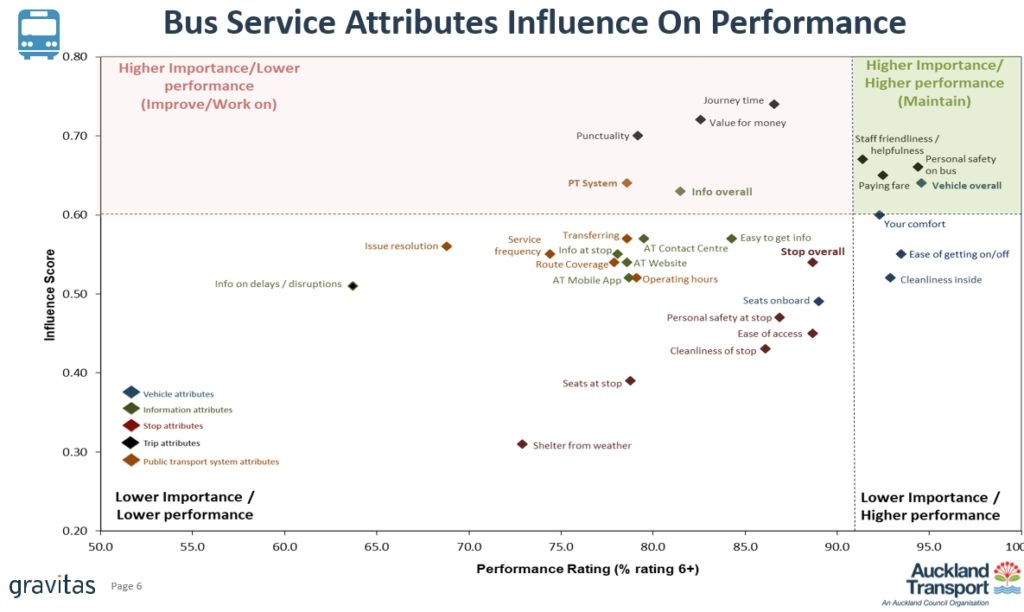

It also includes these charts showing how people ranked the attributes of each mode. It does suggest value for money is important but as per above, value for money could just mean it’s cheaper than the alternative.

Processing...

Processing...

Oh dear, the good old strategic transport model strikes again. Reminds me of those CRL debates where the model said bus use would keep growing massively regardless. When people finally dug into this, apparently the model was running 300 buses per hour along some streets and each bus had 200+ people on it!

No wonder the modelling under estimates the impact of projects to expand PT capacity on future ridership!

Which reminds me that models that contain errors can be fixed and run again at a low cost to society. Whereas saying “stuff this modelling nonsense let’s just pull a Benefit Cost ratio out of our butts” results in building projects that shred money for little gain.

So the main driver of PT use is just the cost of parking. Conversely, almost no one finds it a more stress-free or quicker experience. Hallmarks of a network that isn’t really trying to compete with SOVs, just price them out of the market with scant regard for how fit for purpose the actual service is.

Or maybe a network where not enough people are priced out of parking and driving? I’m sure even in cities where PT is exceptional, if the Council and Government spent most of their money on massive roads and subsidised parking, a lot of people will drive.

If getting people out of cars is literally your only goal, sure.

The idea that people should be expected to use a network that is slow, unreliable and stressful to navigate just because ‘cars r bad’ doesn’t exactly scream ‘livable city’.

You could frame it as ‘stop subsidizing parking so much’.

BW, in most cases PT will never replicate what you can achieve with a car; hopping into it in your drive way and out of it at the destination. AT have tried to replicate that in Devonport with the AT Local and that hasn’t worked.

Isn’t it reasonable to price parking at least at the cost of supplying it? With car parks in the city currently valued at about $80k, just to recover the long term cost of capital at about 5% over 260 business days per year the daily charge would be about $15.40. Of course on top of this is rates, electricity, water, security, overheads and profit etc. AT car parks make a negligible return and probably no return if you add all these factors in.

There’s nothing wrong with pricing parking, but relying on it to drive PT adoption instead of actually improving PT to the point where people want to use it is bad and lazy planning.

To give you an example: I used to have to wait for twenty minutes before my scheduled bus time at my old place to be sure the bus that was coming didn’t erratically and inexplicably come early – but usually it would be late. Now, it was still about as quick as driving, and cheaper too. But was it enjoyable to wait that long in the rain for a bus that may or may not come? Of course not. It was horrific. The only reason I didn’t drive was that I couldn’t afford to fuel a car and park it.

Of course now with WFH being a hot topic post-Covid19, if the car is expensive and PT still sucks, some people just won’t go at all anymore. I just think those low ratings (which you can basically call ‘quality of service’) are pretty telling and we should aspire for them to be much much higher.

Was your bus experiences pre or post New Network out of interest?

I get what you are saying, but part of the reason the your bus was unreliable is likely lack of bus priority. Charging for parking would help address this by being able to pay for bus priority, in turn this would shift more SOV drivers into PT as becomes more attractive. Same goes for the lack of shelter and so so frequency.

The hard bit is making this jump to better PT when there isn’t the parking income to fund it yet. I’m sure they could, just by not forking out on a new big parking lot somewhere. Just needs a change of thinking.

I definitely find PT quicker and more stress free than driving an SOV.

My commute to work takes around 35 minutes catching a feeder bus to Constellation then the northern busway to downtown. I don’t have to do anything but watch the view of the harbour.

Driving would take me a minimum of an hour, and demands constant attention to crawl in stop start motorway traffic.

Needs to be a combination of both aspects but not both in full.

That means improvements, while REDUCING fares. If you cut fares in half you would likely get 90% of the gains of free fares (while also keeping control of the system – less undesirables too – tagging, damage, assaults etc).

If this causes too much peak demand (either improve capacity – DD-Bendy, 6car/7car EMU, etc) or make less reduction during peak but make offpeak cheaper.

I would say a lot of the issue with fares is the overhead of having a card or having to use cash etc. For the typical Aucklander that never steps foot on a bus in their life, they don’t have a HOP card and they probably don’t carry cash, so they will never even try a bus and find out they really aren’t as awful as they imagine / once were.

I’m not sure hopping on a crowded free bus where anyone can ride to use it as a place to hang out or keep warm will necessarily encourage new users.

“Undesirables”. It’s okay, we’re all adults here, you can just admit you think that poor people are thugs.

No Daphne, that is purely inflammatory character assassination on your part – not surprising really coming from you though.

Having an element of cost or ownership (by way of paying) does discourage criminal elements and makes the service more user friendly for other passengers. I have advocated for cheaper fares (which mostly favours poorer people than wealthier people), but cool push your usual wacky agenda…

Sounds like you aren’t Daphne…you sound more like an angry teenager.

I fail to see what the point is of a model in which the PT network improvements are assumed to be incapacitated by some unknown dampening effect (which is what their ridership growth indicates).

A more useful exercise would be for the Auckland Forecasting Centre to model some things I haven’t seen them model:

A business as usual scenario with plenty of growth happening on the outskirts but the housing crisis unabated, so many, many people are stuck in overcrowded housing in outer suburbs with poor public transport and active transport networks, vs

A scenario with government-supported growth happening along arterials shaped into people-friendly multimodal boulevards where buses and active modes have priority, surrounded by low traffic neighbourhoods. This scenario would involve a significant number of people moving into well-connected Transit-Oriented Development areas because it would be both affordable and attractive. In this scenario the “You can’t change much through modeshift” myth is thrown out the window by three things:

– significant land use change

– significant network change at a fine grained level – the low traffic neighbourhoods are cheap, and the arterial boulevards are no more expensive than the BAU bullshit work.

– the latest research showing it has been wrong to ignore discontinuities in travel habits, and in fact disruption is very effective at creating radical modeshift.

I was hoping we might return to some semblance of normality. But Matt thinks we are headed for normalcy instead. Now I am really scared. I think it was Warren G Harding gave the world normalcy.

Bet the ferry users surveyed did not include Waiheke ones. Value for money? lmao.

You use a lot of lame Americanism’s too. In a post above you say “butt”….

I thought is I wrote arse they might delete it.

I guess it’s all relative. It probably is value for money when compared with the alternatives of swimming, kayaking or the cost of owning and maintaining your own boat.

People will gradually forget about social distancing and being super-hygienic.

What will last longer is the global recession that the pandemic has caused. Recovery from that may case in increase in usage of public transport.

Or unemployment will just mean less mobility over both public and private transport.

If you go to Apple.com/covid19/mobility and look up Auckland, you can see that driving has already recovered to baseline, while PT is around -45/-50% below. This trend is even worse in other countries (US has driving +40% and PT -60% and Norway +55/-20). This is a reflection of people being reluctant to board a ‘filthy bus’ while they can sit in a ‘clean car’. Clearly they don’t have young children. I think it will take some time to change that fear.

We’ll see. People might be apprehensive now. But what about in 6 months time?

Like with using the back door on buses during the previous covid-19 stages will that continue ,as it will make it easier and quicker to board and depart , if they are not collecting Cash fares ?

I hope I’m wrong but it doesn’t look like it.

No, it’s front door entry now. I wonder if cash fares will ever come back? I suspect not.

Interesting rankings. Wonder how they arrived at the data?

I think actual users of PT recognise the importance of frequency a lot more than those that have never or hardly ever used it. If they are pretty much only “car users” they will more likely to weight importance of a near door to door service, not having to transfer & total trip time. We really need our frequencies improved, especially on the rail network.

Yes we definitely need improved frequency, and across the board (not just rail). A better survey might be to ask vehicle drivers why they are NOT using public transport.

My hunch is that frequency-related issues (long waits for service to arrive, having to muck about with change-overs, long walks to service etc) will be amongst the top factors propelling vehicle usage.

Good idea. And asking why they don’t walk or cycle or let their children would be good, too.

I see AMP Wealth Management in Auckland and Wellington are closing their city offices in favour of working from home.

Their thoughts are that others will do the same.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/121777578/the-start-of-a-trend-amp-wealth-moves-out-of-the-city

Will be interesting to see how the 70 % respond if they are told by the business what days they have to be in the office, especially if they find out the colleague that they actually enjoy catching up with will be there on different days.

Also were they aware of a proposal to move the office out of the CBD when filling in the survey? This could make the commute more difficult for many.

The idea of having a mix of office and home days is quite popular, it’s my preference too. However, you can only really downsize if you schedule people’s days in the office and have an even number of people in each day.

Yes this and other likely post covid trends leaves me much less optimistic on the future of PT than the author.