A few weeks ago, Streetfilms released an eye-catching video about the small Belgian city of Ghent, and the dramatic changes they made to traffic circulation in 2017. This video should be professional development watching for everyone involved in Auckland’s transport planning.

It seems that rather than “build it and they will come”, Ghent used the concept of “return it to the people and they will come”. When road space is at a premium – as in Ghent, or Auckland – trying to magic up new space and protection for all the neglected modes is futile, and expensive. Much more can be achieved within a limited budget by removing the ability of cars to dominate.

Ghent’s story turns out to be even more interesting than the video shows. I’ve put a list of lessons for Auckland at the bottom of the post.

Belgium is known for its car dependency, making Ghent a useful city for Auckland to watch. Although there are differences in urban form, we share many political difficulties in developing a sustainable transport network. I was inspired to find out more about how Ghent got to a point where it could make such fundamental changes. What I found reminded me of the approach that other cities have used to successfully transform their networks. Common elements are:

- comprehensive, sustainable planning,

- excellent communication and public engagement, and

- crucially, having a visionary politician or spokesperson lead the plans. In Ghent’s case, the deputy mayor stepped up with the energy needed to empower and channel the enthusiasm of the planners, and to bring the public along.

Also, instead of gold-plating and expanding slowly, Ghent used cheaper solutions over a larger area to achieve fast results. They sought the easiest way to implement key concepts, rather than roll out standard engineering templates. This means less need for hard engineering solutions and expensive streetscapes. Inspired by the Dutch cities of Utrecht and Groningen, Ghent’s transport planners sought a way to ‘catch up’ fast:

We took a shortcut… without hard and expensive infrastructure.

The City of Gent is situated in the East Flanders region of Belgium. It has a population of 243,000 – Civitas

[Ghent dates] back to the Middle Ages when it was the second most important city in northern Europe after Paris… During the 1980s, the city centre suffered the impacts of increasing car traffic, including congestion, air pollution and noise… Public transport had little or no priority and conditions for cyclists and pedestrians were deteriorating. – EC Streets for People

Gent … committed itself early to the principles of SUMP [Europe’s “Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning”] and successfully transformed from a car and traffic dominated to a people and quality of life focused city… – Civitas

In 1987, the first major plan to reduce congestion was reversed after only 5 months, because of opposition:

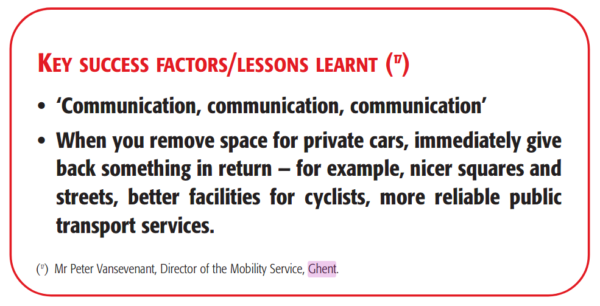

The City of Gent recognised that the plan was poorly planned, as there were no accompanying measures, such as bicycle policy, parking policy, public transport or refurbished streets and squares to help people access the city centre sustainably. – Civitas

But they didn’t give up. A decade later, in 1997, the plan was successfully reintroduced – this time, accompanied by other measures and better communication:

- Comprehensive bike policy to promote cycling (implemented in 1993)

- Increased public transport frequency and coverage

- The construction of underground car parks

- A dynamic parking guidance system

- The renovation of public spaces – Civitas

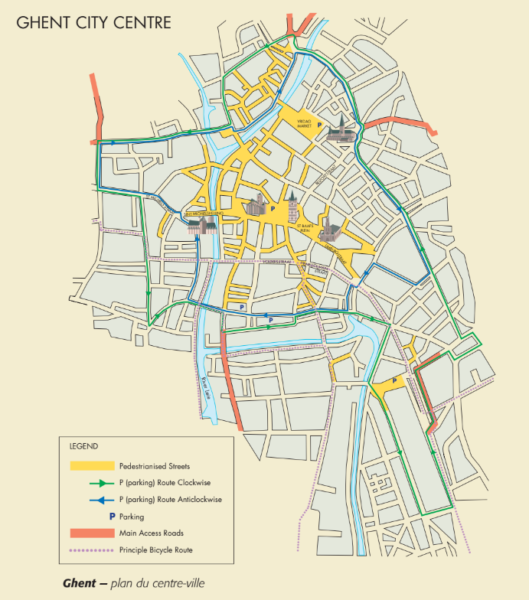

The 1997 plan covered 35 ha in the central city:

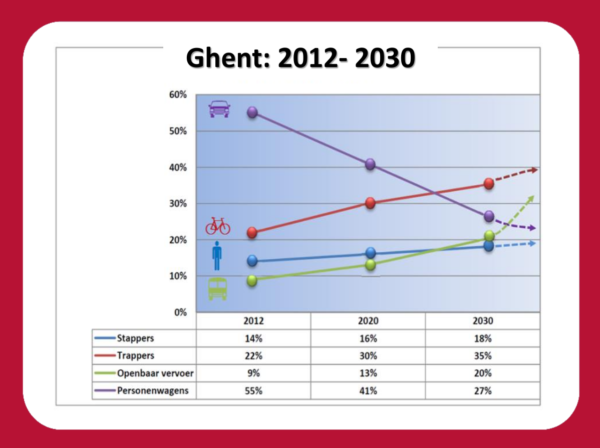

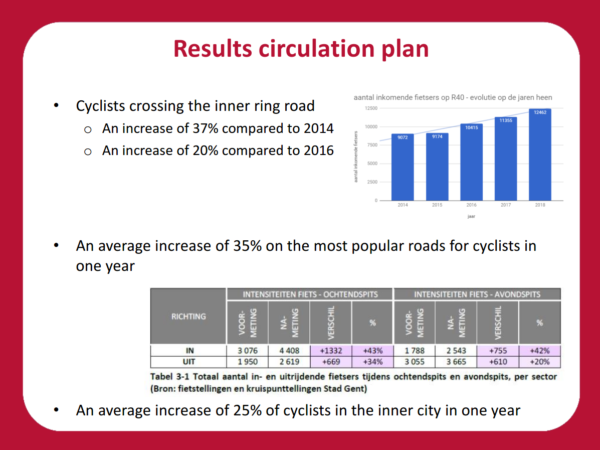

Further improvements in sustainable mobility continued to be made between 1997 and 2012 – which is when Ghent took things to the next level, with its boldest mobility plan yet. The plan set clear targets for mode share: halving the number of journeys by car, and doubling the use of bikes and buses. From a 2018 report:

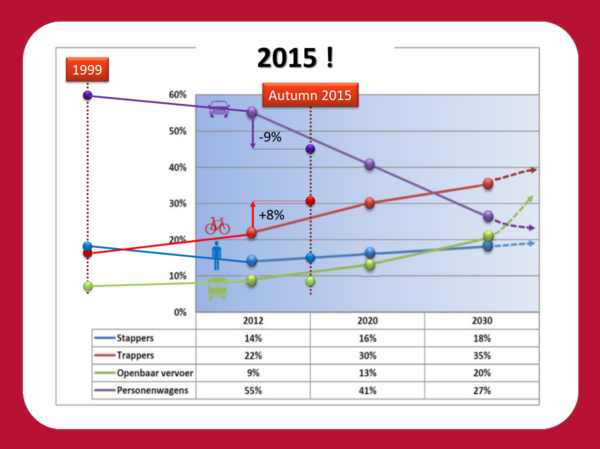

By 2015, progress was healthy:

With the help of all the ongoing improvements and the circulation plan, the 2030 target of a 35% cycling mode share was reached 11 years early, in 2019!

we have the modeshare of 35% which was actually the target for 2030, so it seems that we have to rethink about the targets.

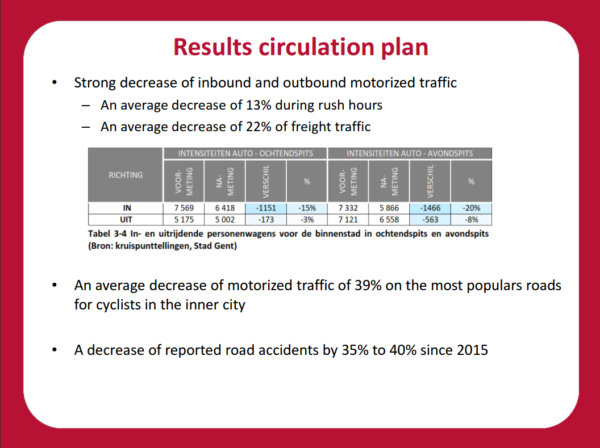

Here are some more results, again from the 2018 report:

Not surprisingly with these great outcomes, citizen satisfaction rose. By 2018, Cadence found that even those who weren’t yet convinced made positive changes to their mobility habits. This week, The Guardian newspaper reported on stories from residents:

Not surprisingly with these great outcomes, citizen satisfaction rose. By 2018, Cadence found that even those who weren’t yet convinced made positive changes to their mobility habits. This week, The Guardian newspaper reported on stories from residents:

The changes have made an enormous difference to people’s quality of life…

My advice would be to focus on the whole city not just a small area to not disadvantage people who are not able to afford to live in privileged areas…

If your city is planning to do the same my only advice is: don’t listen to the haters.

So what did the the 2017 “circulation plan” involve? Firstly, it happened nearly overnight, something they recommend over the sort of staged changes that Auckland is trying to do:

Watteeuw advises Birmingham’s councillors not to stagger any changes.

“In Ghent, we implemented the plan as a whole overnight,” he says. “It was technically and politically the easiest way.”

Near the city centre, Ghent’s plan included 15 ha more of pedestrianised area with limited vehicle access. In some pedestrian streets, people are required to walk their bicycles rather than cycle:

But the more substantial changes affected traffic flow over a much larger area – the 700-odd hectares within the R40 ring road. So it’s roughly 20 times the size of the 1997 plan.

To prevent cars to needlessly traverse the city center, the Circulation Plan divides the city into 6 sectors and one big carfree/pedestrian zone.

Creating the sectors was achieved in many ways depending on the location, including

- signs, paint markings and cameras, allowing certain types of vehicles to pass,

- simple barriers that rendered streets closed to vehicles, but open to walking and cycling.

Lowering traffic speeds was, of course, important. The 1997 plan had already introduced lower speeds:

speed limits in the pedestrianised area have been reduced to 5 km/hour for those with permitted motorised access. – EC Streets for People

And the 2017 plan introduced survivable speeds across the larger swath of the city inside the ring road.

The speed limit is 30 km/hr here… it is quite safe and you don’t always need separate bike lanes…

Lowering traffic volumes was equally important – something Auckland’s planners need to be designing into our plans:

If you set up a cycling street, you really need a low intensity of cars. – Streetfilms video

Here are some more of the changes made in 2017 listed on the official information page in anticipation of the plan:

- Transit traffic [i.e. through-traffic, rat-running] on important roads will be prevented by closing streets for motorized vehicles.

- There is a change of travel direction in various streets.

- The inner ring (R40) will get you from section to section.

- The main ring road (R4) will get you from municipality to municipality.

There was also a full parking plan with tiered pricing, streets where cars can’t overtake bicycles, and cameras to help with enforcement.

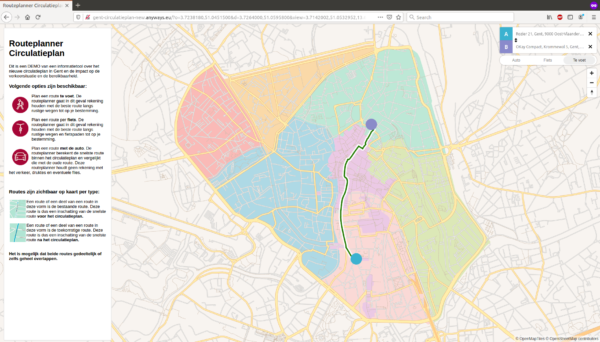

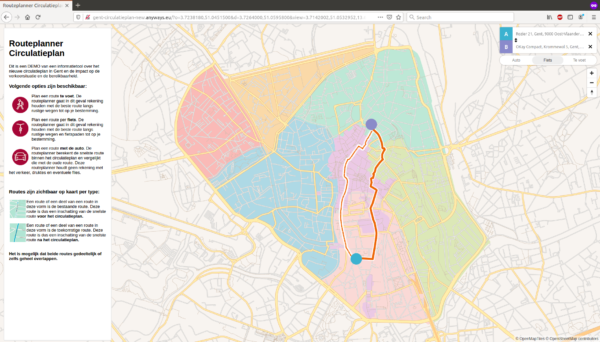

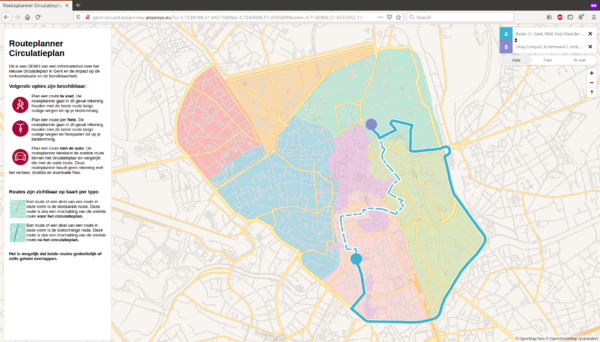

If you’re interested in learning more about the specifics, you can zoom in on this interactive map. The following gif indicates the sort of information layers available, including the cycle routes, tram and bus routes, sectors, filters, parking lots, and changes to one-way and two-way streets.

The communications material for residents and visitors was very good. Here’s the app Ghent produced to help people understand how to get where they wanted to go. In particular, it shows what the route would have been before the plan (thinner lines), and after the plan (thicker lines).

Here’s one example. The walking route hasn’t changed.

The cycling route has changed, to avoid a no-cycling street:

And the driving route has changed:

And the driving route has changed:

Seeing this, many people – including some traffic engineers who haven’t kept abreast of new research – might assume the traffic would increase because “everyone would have to drive further.” Yet in practice, traffic volumes reduced considerably as people chose different ways to reach their destinations. And less traffic meant nicer spaces, cleaner air and a more active population. Above all, Ghent offers a brilliant illustration of traffic evaporation and mode shift.

Credit: http://www.ppmc-transport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/04_Pelckmans.pdf

Public transport ridership and car-share rose, and an economic report suggests retailers have mostly benefited from the changes.

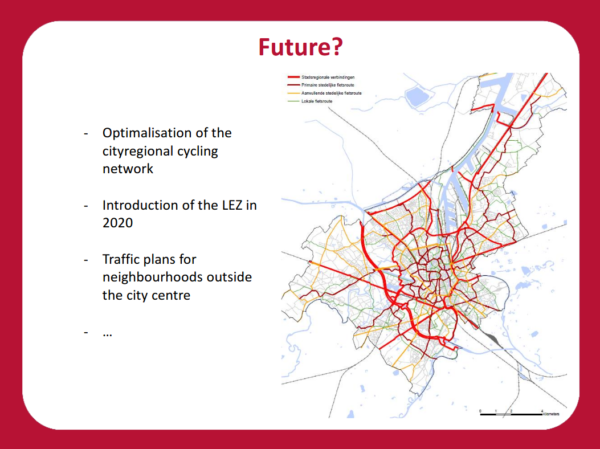

Other cities, like Birmingham are taking the lead from Ghent. And yet Ghent is still aiming higher:

Where the car traffic has not been reduced and where cyclists and car drivers can’t share the space, the City knows a plan must still be conducted to improve the standard of cycling infrastructure. During the next six years, the City is going to improve cycling conditions beyond the ring-road. – Cadence

There are lots of lessons here for Auckland:

- Car-dependent cities can change radically – but it requires steady work.

- Many of the changes can be cheap, quick and reversible, and implementing them quickly is better than staging them.

- Transformational change is often led by a visionary politician, or a visionary transport planner enabled by a politician. In Ghent’s case, it was the Vice Mayor, Filip Watteeuw, whose steadfast, cheerful and evidence-backed promotion of the plan and its benefits helped steer the city through the process.

- Success seems to result from having a comprehensive Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMP). One way SUMP plans differ from what Auckland is currently doing is in setting significant mode shift targets, and using significant reduction of traffic volumes as input to the travel demand management.

- Adding cycling infrastructure alone isn’t enough; cycling mode share rises as traffic volumes (and speeds) are reduced. So it’s not just about adding bike lanes where you can; it’s about reducing the threat level overall. This works to encourage more walking, too, especially for kids, the less physically able, and the elderly.

- More progress is made, and faster, when you work with a larger area – and when the traffic circulation is designed more comprehensively.

- One-way streets are not something to fear if they are part of an entire circulation plan. They can be a good solution when the road corridor doesn’t otherwise provide enough width for all modes and goals.

- While it may seem like driving will become “harder” if routes are more circuitous, in fact the lower traffic volumes mean driving can be less stressful.

- Communication, public engagement, and public access to quality information are absolutely critical.

- Every city has vocal naysayers, whether private citizens or political parties – but they shouldn’t prevent demonstrable progress for the planet and the population.

If there is political will to make really good changes towards more walking and cycling and really making the city more pleasant and happy… on a political level, people get rewarded for it. – Streetfilms video

Not gold-plated – but sunny yellow, and effective. C

Edit on January 24: The Dutch Cycling Embassy has tweeted:

First it was Ghent. Then Birmingham. And now Auckland…

Pioneered in the Dutch city of Groningen 40 years ago, 2020 just might be the year of the Traffic Circulation Plan.

Learn more about the New Zealand city's ambitious Access for Everyone (A4E) Plan: https://t.co/kwmNkPkRYv pic.twitter.com/dGPgX27uwt

— Dutch Cycling Embassy (@Cycling_Embassy) January 23, 2020

Processing...

Processing...

The Plans are all there but we know Auckland Transport just is not capable of doing this.

It wants to do 150km of cycle lanes over 10 years (we have over 1000km of urban roads) and gets over excited when it does 1 metre more than the SOI stated for the year.

We have an AT CEO that gets excited about loss making public taxis and tech bro solutions while not exactly caring for buses.

Until a broom is put through AT none of what is mentioned in the post will happen.

I don’t think attacking the staff personally, even at the top, is the best way to achieve change. What’s clear from all the cities making successful, enduring and often radical change is clear ambitious leadership from the political level. Paris with Hidalgo, New York under Bloomberg, Madrid’s previous mayor… etc.

I think at the technical level there is a great deal of confusion, not least because they get attacked, often personally, and sometimes viciously, whatever they do. This is because there are polarised constituencies out there. Those that fear change, that are used to total car priority and have yet to discover the freedom and improvements that come with experiencing urban places with no or fewer cars, are loud and entitled and complain too.

So those who want change are better to lower the violence of the discussion and ask for leadership from those whose job it is to provide it while presenting evidence and urging professionalism and imagination from the technical level. Increasing fear levels is unlikely to lead to creative action.

You might be right about “attacking the staff personally” as that only persuades those staff to dig their toes in.

Removing those staff and starting again from the top would be a far better idea.

The best idea however would be to have the Super City legislation changed to give Auckland Council direct control over all it’s CCOs

I’m not sure progress would be any quicker if our current crop of councilors had direct responsibility.

Thanks for this post, the line ‘don’t listen to the haters’ note easy, here are my notes on Groningen circulation plan and the push back from the business as usual people

http://hamiltonurbanblog.co.nz/2019/09/groningen-%e2%80%93-introduction-to-traffic-circulation-plan-vcp/

typo ‘not easy’

When Max van den Berg proposed a plan in 1977 that made the centre of Groningen virtually impenetrable by car, his party was the subject of outrage, protests, and death threats. Now not a single resident misses the days when cars choked their streets. Fortune favours the brave.

Thanks, Peter. Interesting stuff in there. The unnecessary concern about parking is interesting, and how they ended up not needing to build the parking building. “Parking: the proposed Sledemenner-straat parking garage was ‘completely scrapped’ (p35)” At least that’s one urban form difference with Auckland that makes things easier for us! There’s certainly no call for more parking; we have about 20,000 spaces more in our city centre than even Sydney does.

Yes this is a great advantage Akl has; all the driving and parking amenity is already in place, has been for years, PT is catching up fast, bike lanes less well, but still at least moving.

Actually if anything I see a problem here in how cheap and easy this is; there are no endless $$$millions for big contractors and engineering consultancies to grow fat on here.

Remember they led the charge at the beginning of the motorway era, funding study tours to the US and publishing documents full of pics of mostly empty diamond interchanges on sunny days contrasted to gloomy pics of trams nose to tail in Queen St…

That’s what I was wondering. This could potentially save us billions of dollars, if it means we can stop the silly highway widening projects.

It’s cheap, and reversible. It looks to me like we should be spending the money to do this, and then change things if some part of it is wrong. Less money wasted than many an individual roading project. But the potential for finding real gains and a whole different approach seems high.

Auckland is such a spread out city that yes in some local areas some of this could be achieved but a big problem is the number of people that live on one side of the city and work on the other. Look at the nightmare traffic when they did roadworks on AMETI last week and just closed a couple of lanes. More than AMETI is required to make any drastic car ownership change and use and have any great effect. In that areas maybe they should be looking at reducing speeds in certain residential streets too. A little off topical but I’m just looking at it from my local area.

“the number of people that live on one side of the city and work on the other”

You don’t think that happens in any other city?

Considering the average commute in Auckland is 5kms, I suggest the number of people making these “supercommutes” are really a minority. A minority who will probably continue to drive.

We don’t have to mkae changes that mean 100% of people travel differently. If we managed to get 20% of people to to PT or cycling, that would be a massive improvement.

Erm, we built a vast motorway right through the city for this. Those that want or need to drive ‘from one side to the other’ are more than catered for.

A motorway that is heavily oversubscribed and not fit for purpose in the absence of usable alternatives? That’s like saying we don’t need separated cycleways because you can in theory just ride on the road. Your chances of being killed are exponentially higher, but if actual function doesn’t matter, then why are we bothering?

Are you concerned about safety on the motorway for people driving from one side of the city to the other, or are you just talking about cycling? (Just curious.)

Clearly we don’t want to increase the motorway capacity and induce more driving; rather we want to make it less “subscribed” by reducing traffic volumes.

That’s what’s so cool about the UK low traffic neighbourhoods, Ghent circulation plans, Barcelona Superblocks – by enabling enough neighbourhoods to revert to being calm neighbourhoods, the modeshift is so substantial the arterials and motorways see lower volumes.

Heidi: I am more taking issue with the idea that those who have to drive to places like North West Auckland are ‘more than catered for’. If the fact something is there is good enough, regardless of how well it functions, then why bother building anything? The bare minimum should be good enough for everyone.

We don’t accept that sort of logic when it comes to cycleways and we shouldn’t accept it when it comes to tediously slow rollout of driving alternatives and modeshift in the North West.

We only need to mode shift 50% of the current and all the new light vehicles in Auckland away from fossil fueled (emissions) to other modes – bikes, walking, and PT. Plus EVs in the short term, but in the long term leaving that space for those that can’t get out of their cars.

I doubt the average commute is 5km. Unless you include children commuting to school and stay at home parents commuting to the kitchen.

5km from CBD gets you to Westmere or just over the bridge.

“The report, released on Monday, claims two-thirds of car trips made for commuting between 2015 and 2017 were within a comfortable cycling distance (five kilometres or less), while one-third were within a reasonable walking distance (2km or less). ”

https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/112311772/kiwis-need-to-halve-car-use-by-2050-to-sufficiently-improve-health

Regardless of distance – short trips create congestion for long trips. Shifting to active mode is about removing these short trips that block the transport system.

Maybe read the article. The claim is for NZ not just Auckland. Given the source is Stuff I wouldn’t rely on it.

It’s urban areas, and the data is from the Household Travel survey. I don’t have the particular spreadsheet the report used but I do see in the MoT data that of the urban areas, the average km travelled by car for drivers and car passengers in Christchurch is high and pushes the national average up, with Wellington, Auckland and other urban areas lower than average.

The report itself, Turning the Tide, says:

“If we assume that 2 km is a walkable distance and 5 km is a cyclable distance, in urban areas in New Zealand nearly one-third of all car trips are within reasonable walking distance and nearly two-thirds of car trips are within reasonable cycling distance.”

It’s an important point; doubting the distances involved just prevents taking the opportunity of providing active mode choices for people.

The assumption that a trip can be cycled if it’s 5 km is very conservative. I’ve seen consultants using 6 km for this but with e-bikes I believe the distance is being increased significantly for new analyses.

http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/Maps_and_geography/Geographic-areas/commuting-patterns-in-nz-1996-2006/distance-travelled-by-commuters.aspx

Admittedly this is 2006 but median in the 4 cities of Auckland (North Shore, Manukau, Waitakere, and Auckland City) is only 6 km.

Well I suggest your doubt might have to give way to the facts set out above. Doesn’t back up 5kms average, but a 6 kms median is even better to prove the point.

That suggests that if you were to eliminate the longest 5-10% of commutes, there would be almost no need for infrastructure for cross city commutes. Effectively meaning we are building these huge motorway systems for a fairly small % of drivers. Perhaps around the same as the number those taking public transport – which of course is a “waste of money” and “not used by anyone”.

It also means that 30-40% of commuters could easily get out of their cars and commute by bicycle, bus or train if the option was given to them. And I suggest that is exactly why we are seeing so much growth in PT and cycling numbers.

Stats are great. You can read into them what you want to see…. The quoted stats are taken from census data. Dig to the source and you see the 6km is a straight line from centre of home suburb to centre of work suburb where the information was given. 47% of NZ live within 5km line of sight. I live just under 5km from my work but my normal commute is over 7km. Of course you really need to look at upper quartile data to capture typical commuters where it was 11.6km line of sight for Auckland.

BTW I am not saying there isnt a need for better infrastructure for cyclists. Although as this article suggests it doesn’t need to be gold plated as pushed for by made if this sites readers.

True about reading what you want from stats. In the same vein, is there a reason why you wouldn’t include the travel of children commuting to school in an average commuter travel stat?

The HTS doesn’t include children, and of course that skews their average trip length statistics upwards.

Heidi, when I was involved with the HTS a few years ago it included everyone in the household, of whatever age.

I hope that that hasn’t changed – children’s travel is at least as important as anyone else’s.

Thanks, Mike. I doubt anything’s changed, so that’s interesting to hear.

The brochure says: “An interviewer will provide your household with a survey kit. The kit contains Travel Loggers for

each person (12 years and over).”

The FAQ says, “Children under 12 will not be asked to carry a Travel Logger. However, if you are taking part and have children under 12, you will be asked about their travel.”

I’ve heard users of the data consider it misses children’s travel. If there wasn’t a log provided for each child for the parents to fill out, do you think the questions about their travel are precise enough? Maybe that’s where the issue lies – generalised questions are usually incomplete and less correct. I’d love to hear more about how it worked when you were there.

I don’t think you’re off-topic; I think you’re musing on all the right challenges.

What I’m learning from all the different cities I’m looking at is that the key is having the intention to reduce the traffic. The way the solutions will be implemented will be different for different cities, but having this core intention is critical. Currently, Auckland’s battle is really difficult because while there’s progress in one area, the lack of this key intention removes that progress in another.

You’re right that reducing speeds in the residential streets would help. Keeping through-traffic to the arterials, and out of the smaller streets in neighbourhoods, can happen throughout the city. The traffic reduction would be considerable.

And yes, more than AMETI is required. It’s not just expensive projects to add new infrastructure we need. It’s putting what we have to better use, cheaply and comprehensively.

“the number of people that live on one side of the city and work on the other”

You don’t think that happens in any other city?

Considering the average commute in Auckland is 5kms, I suggest the number of people making these “supercommutes” are really a minority. A minority who will probably continue to drive.

We don’t have to mkae changes that mean 100% of people travel differently. If we managed to get 20% of people to to PT or cycling, that would be a massive improvement.

A similar plan for Wellington city (not region) central city area was promoted in 1963 and it still talked about. Like with Ghent, it is simple to introduced and can be done ‘overnight’. But our so call theoretical urban transport planning bureaucrats, weak Wellington City Council and an out of touch GWRC keep having talkfests and pat each other on the backs for doing nothing, mean while the central becomes for more polluted with nasty fuel and noise emissions.

Like Chent, Wellington is public transport, walking and cycling friendly city and should function as such.

Could you provide details of that 1963 Wellington plan, Kris? It would be good to see what was proposed.

agreed. Wellington seems like a perfect city in NZ to introduce those improvements.

Heidi writes “Instead of gold-plating and expanding slowly, Ghent used cheaper solutions over a larger area to achieve fast results”.

I think we more of of this. For example the less than 1km of bikeway on Victoria St will cost $5-6million. Wouldn’t some standard barriers do the job. No need for digging and resurfacing

You would think so but once you consult with Auckland wide, change the design several times, upgrade bus stops, cater for improved pedestrian movements, improve stormwater, improve overall road safety, add in some urban design and resurface the whole road. Suddenly $5 – $6M seems cheap.

Fundamentally much of Auckland’s infrastructure is poor. So often a adding cycleway is really upgrading the street to modern standards.

Sprawl makes the situations worse. As we have a lot of roads that need upgrades.

You’re all correct. So the question becomes, are we happy to go at snail’s pace and fix everything up properly every time we do something?

Or do we owe it to our population to use best practice? At this point in time I’d suggest best practice is something faster and more radical, with the actual repair of surfaces and infrastructure continuing steadily in its wake.

The problem with doing it slowly and well is that without the modeshift that we’d see from doing a comprehensive plan, we’re likely to get new streetscapes that still allocate too much space to private cars, but set in ‘stone’ with hard infrastructure that won’t be redone for decades.

I think we’re going down the most expensive route we possibly can.

It’s the 80/20 rule, innit: Much more of the value is in the better street pattern than in the well designed and more permanent materials. So deliver that higher value layout changes to more places quicker, test, refine, and steadily make solid and durable over time.

Basically what we are arguing is that Tactical Urbanism should be best practice.

I think our roads in Auckland are near perfect. Beautifully smooth and cleaned often. Some have patches but our vehicles don’t notice them. I have asked before if anyone can find and let me know of a bad road in Auckland.

@Jim – I don’t believe upgrading has anything to do with this lovely, smooth tarmac you are referring to but to do with the antiquated storm water system which Auckland has which has been neglected for shinier election winning infrastructure.

This is a good discussion to be had. I think perhaps some of the more central city ones like Victoria St are best done “fairly gold plated” but yes it is a slow process so far. Further out we should be slapping down the barriers, removing on street parking or wide general traffic lanes.

You’re probably right, Jim, that the road asphalt is often maintained to a high standard, albeit with rough chip seal. But this is probably at the cost of spending money on basics in other ways. “Upgrading the street to modern standards” is much more than the pavement surface.

It includes the layout of intersections, which are fundamentally deficient in Auckland – legless crossing, slip lanes, dangerous wide kerb to kerb, footpaths too narrow, bus stops too far from intersections for catchment walkability or transfers.

It includes the widths of the roadways, which are often too wide, encouraging high speeds.

It includes the form and maintenance of the gutter, which is often where cyclists end up, and is lethal, with leaves hiding dangerous changes in level and piles of loose gravel or rubbish.

It includes the state of the footpath – look at Rosebank Rd’s footpaths and verges for an example of hazards caused by allowing trucks to manoeuvre all over pavements not designed for their weight.

It includes the basics for personal safety, like lighting.

And then there’s all the other infrastructure, like water, stormwater and wastewater pipes that haven’t been maintained for decades.

AT just aren’t moving on this stuff. Look at Queen St.

The plan should be for AT/AC to identify one of these simple changes each month. Local wards can propose the priorities. They can have 2 a month if they so wish.

This time next year, we would have the successes to be made permanent, the failures to be dumped or reworked. And a new list of projects would be oversubscribed based on the transformational effect of the first year.

Its not that hard, surely.

Everything is hard for a public department.

Perhaps AT should be privatised…

Jimbo

Privatising for the reason that you have mentioned is well worth exploring.

Great research with lessons for many towns and cities throughout New Zealand. We seem to battle it out for every cycleway, pedestrian crossing or traffic calming measure street by street. Yet for all the reasons set out in the article we need dramatic modeshift and this requires the sort of wider plan seen here. I look forward to the day when our local Kapiti cycleways are full of ordinary people using bikes to get around rather than simply using them as a leisure activity.

Thanks for posting. I do love these case studies that show what is possible. It is very impressive growth in a short space of time, but the baseline mode share for cycling was 22%. My sense is that there isn’t yet enough of a critical mass in Auckland to make an ‘overnight’ change anywhere near politically palatable. Don’t get me wrong… I ‘d love to see that! But would require an incredible amount of political bravery – even more than was shown by the deputy mayor of Ghent.

Thanks Joe. Ghent’s cycling modeshare was 22% in 2012, as you say.

In 1999, from the chart I’ve included, it seems it was just below 18%… not sure what it was before the 1997 pedestrianisation, nor before the 1993 cycling plan, but we can assume it was below 18%. I’ve seen one mention of 14% but couldn’t pin it to a particular year. It probably wasn’t as low as Auckland’s but then again if you look at Auckland’s modeshare in different areas, there’s a big difference here too.

Another city to look at is Berlin, where making the residential streets 30 km/hr brought many safety improvements, as intended. But unexpectedly (for the time) it also boosted cycling modeshare, as people found they could cycle safely. And this is what created the public desire and pressure for safe cycling infrastructure on the arterial roads.

What Ghent (and Barcelona, Utrecht, Groningen, Waltham Forest, and so many others) show is that in addition to “just” providing safe speeds, we can cut the ratrunning, and speed this modeshift up.

Paris saw 54% increase in cycling last year thanks to radical changes, and is about to adopt Ghent’s circulation plan concepts.

And of course this isn’t just about cycling, but about freedom for people to move about in a healthy streetscape, and to have choices in transport.

Indeed, instead of seeing Auckland as “more difficult” to improve, I think the opposite is true. There is so much “low hanging fruit”; so many simple things we can do.

We’re one of the most car dependent countries in the world, and Auckland is improving despite of many in our incumbent transport sector, not thanks to them. That doesn’t define us; it defines our limitless options to improve.

5% seems to the critical level to get anything new to a foundation from which to launch it into take over. Seems to be the case for renewable energy, EVs, cycling, anything transformational.

Anecdotally I’m seeing sudden new levels of riding on my journeys, no idea what the numbers are, but heaps of people I’ve never seen before at unexpected places and times of the day.

This is feels like a sneeze waiting to happen…

Heidi, you know that I am strongly supportive of what SUMP programmes have achieved in many European cities, but the common thread is that they are European cities where the expectation of the EU for change is strong.

Of course in a couple of years NZ may have a framework and targets.

I think you give too much credit to what Auckland has achieved and we just have to go back to the narrative from the ATAP report of last year where it said that while significant progress has been made in reducing inner city mode share, none has been made elsewhere.

Having made this pessimistic comment I believe Auckland should embark on a SUMP consultation as, at least, it would provide a start that work could proceed on what has been agreed, and perhaps curtailing work on projects where agreement has been reached that they shouldn’t happen.

Joe

I accept that not all politicians are lining up to reduce emissions. In one of the most bizarre political comments of this year, Paula Bennett, talking about the new education curriculum that suggests that everyone should eat less meat for the benefit of their health and the climate, says kids the resource is aimed at – aged 11 to 14 – are “smart” and should be given the “counterarguments” to what the scientists claim.

I wonder if our schools will also be teaching that binge drinking is good for them; and reintroduce the flat earth theory?

Yes, people keep confusing politics and science. There are always counter arguments to politics but not really to science.

Science requires a critical open mind and ongoing review of theories with new evidence, hypotheses, and methods. At best we can have a high degree of confidence in a result, or set of results. It’s a bad idea to say that the consensus view at any point in time is fact. Otherwise we’d never change our minds about anything. E.g. I prefer germ theory to the previously widely-accepted miasma theory.

The history of research into the causes of stomach ulcers is instructive of how the scientific method operates and how consensus changes. There are sadly many systemic biases to what research gets funded and published, or how some research is reviewed, published, reported or otherwise received, on top of the long list of potential biases in individual pieces of research. We can’t have certainty, only a much greater degree of confidence in the validity and limitations of a theory (and ideally a numerical measure of the degree of confidence).

I do think that there is a strong argument that people should eat less meat for their health and to reduce climate impacts (not least from historic and ongoing deforestation). But the debate and research should not stop now. What of the hypothesis that within a permaculture system, rather than an industrial farming (monoculture/feedlot/etc) system, animals enhance soil health, which locks up carbon and reduces the need for other fertiliser inputs? That should be researched, rather than saying ‘no counterarguments’.

I guess any counterarguments could also be somewhat outside of the scientific method (ethical, economic) and would want to be contextualised as such. Anyway, we can’t be afraid to debate and contextualise these things. The scientific method is the best tool we have to drag us out of the dark ages and all science education should continually emphasise that there are no ‘scientific facts’ as such. As you point out, it’s important to distinguish the scientific method from other ways of presenting information (such as religion and politics) and interpreting information (numerous heuristics and biases…never more topical than with social media echo chambers).

She brought the good news from Ghent to Aucks.

I was in the dark for a while but with help I got there. 🙂

But where is our Roeland to bear the whole weight of the news which alone could save Aucks from her fate?

Ah I was going to shut up, but…

It has been established before that cheap basic solutions at large scale are not wanted here. Snobbery against painted lanes, etc.

See the past 10 year plan, featuring a mere 150km of bikeways at huge cost.

I don’t think you’d see Ghent using painted bike lanes in high traffic 50 km/hr zones as part of their planning, though… this is cheap and safe, not cheap and dodgy.

Yes. The video I link below talks about more physical separation in higher speed zones. Lower speed ones often just shared mixed traffic. Of course here we need to pick up the enforcement.

Yes, use it where appropriate. You can see plenty of painted lanes in that video as well. With some strategically placed bollards in some cases.

Great success story.

So Auckland should implement a circulation plan:

https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/have-your-say/topics-you-can-have-your-say-on/city-centre-masterplan-refresh/Documents/access-everyone-summary.pdf

And 30km/hr speed limits:

https://at.govt.nz/projects-roadworks/safe-speeds-programme/speed-limit-changes-around-auckland/#toknow

I look forward to it!

I’ve just added at the end of the post a new tweet from the Dutch Cycling Embassy that mentions our A4E.

https://twitter.com/Cycling_Embassy/status/1220315512246296578?s=19

Yes, this is our first traffic circulation plan. I hope:

a/ AT roll it out overnight as recommended by Ghent’s planners, and

b/ It’s the start of a much more comprehensive plan for the whole city.

Great post thanks, also watched the video.

Interestingly others may have noticed that the city almost borders the Netherlands which of course is a great example of a cycling country.

Don’t want to be off topic but another great video on similar topic here: https://youtu.be/kp3s2EP0zVo