This is a guest post from reader Heidi O’Callahan

If Auckland is to reach its full potential, roads and streets need to perform beyond the traditional norm of moving traffic and providing access for vehicles to local destinations.

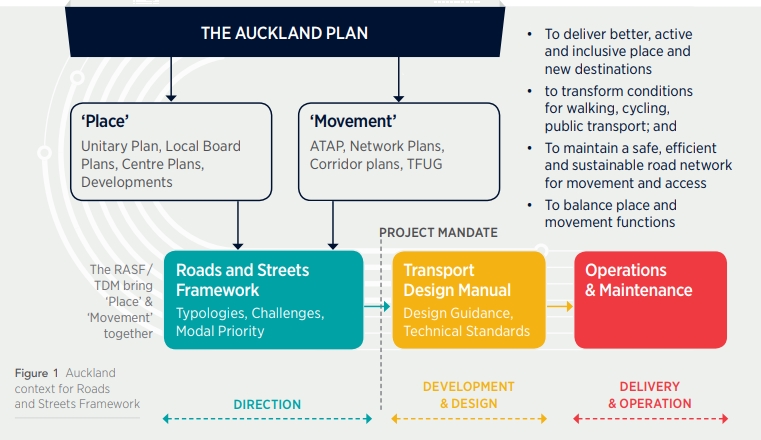

Auckland Transport does some great work. Last year, the AT Board approved a potentially game-changing document, The Roads and Streets Framework, plus its supporting technical document, the Transport Design Manual. But their latest Statement of Intent, released in early July, has sent shock waves through the community of people working to usher in a more liveable city.

It’s worthwhile taking a bit of time to look at the documents and appreciate how they could improve our transport planning, and it’s worthwhile doing so now, in urgency. The Statement of Intent has indicated a review:

Review the Roads and Streets Framework to clarify its emerging financial implications.

Mild words, hiding layers of disagreement and conflict within AT. And somewhat surprising, given that The Transport Design Manual hasn’t even been released yet, so a review of any meaning, taking feedback from practitioners in the field, is impossible at this stage.

For ease of reading, I’ll refer to the Roads and Streets Framework, as ‘The Framework”.

OK, so why did Auckland Transport need this document? Here’s what The Framework says:

The key problems with current approaches include:

- Conflicts between different modes of transport are not being resolved.

- Lack of guidance on network development to support new urban areas, so that they are less car-oriented than traditional suburbs.

- Limited ability to respond to the wider needs of liveability, sustainability, active transport modes and economic growth.

- Development of silos within and between transport and other infrastructure providers utilising road and street space.

- Lack of strategic direction and design guidance in how to address the pressures of growth in existing urban areas and new growth areas.

It’s certainly refreshing to read an AT document that so clearly names some of the problems we face. What seems to be new in The Framework is that its process requires the consideration of the high quality environment and people-friendly work done in other silos in AT and Council. The Framework overtly acknowledges the conflict between different goals and modes, and puts the decision-making around this conflict front and foremost in the process, before the technical design starts. That’s good for transparency and should produce a robust design that can either find wide support in the community, or at least have well-documented and locally-relevant reasoning presented with it.

By considering both place and movement, the key stakeholders together determine a “street typology” which then guides the technical design. Each typology will have characteristic land-uses, traffic types, speeds, widths, travel volumes, pedestrian numbers, etc.

The resulting road or street type is based on the desired future state, capturing land-use and transport aspirations over 10 years and beyond.

Terms like ‘place’ and ‘movement’ sound like the talk of urban planners, but they do express the concepts important for a well-functioning city. We like nice places, but only if we have access to them. We like to go places easily, but we don’t want to ruin all the places along the way with insensitive transport infrastructure. And if places close to home are lovely, we feel less desire to escape somewhere better, putting less pressure on the transport networks. At every location in the city, there’s a balance between how nice the place can be, and how much it can be a place for moving people around.

Of course, every location is unique. The chosen typology starts the process with an initial guess at how the different modes should be prioritised (see the following chart). But once the local information is considered, the priority for that location is likely to change.

The Framework then presents tools to solve or mitigate the inevitable conflicts that arise between different modes and between place and movement goals. Sometimes, for example, all the goals can be met if the street functions differently at different places along its length, or at different times of the day.

I have already found the general recommendations for good urban design and recommended street layouts helpful. For example, design ideas that make good sense in urban permaculture design are now supported by principles from The Framework, such as:

- Walking is the fundamental unit of movement in neighbourhoods

- Block sizes and intersection spacing must be set to provide excellent levels of accessibility for pedestrians

The Transport Design Manual, which details the engineering design, was supposed to have been released at the end of November 2017. Here’s what AT say about the design part of it that deals with urban streets and roads:

I like the “best practice” and “international research” bullet points! Realisitically, it will need to be a living document, like the AT-COP it replaces was supposed to be. And this is where its delay is of concern. As I understand it, the Transport Design Manual includes design guides, engineering code and engineering specifications. At about 2000 pages in length, they can’t expect to get it perfect first time. There have undoubtedly been good reasons for the delay to date. But the team need to get it out into the practitioners’ hands now so that designs aren’t compromised, and so that the practitioners’ feedback can be considered.

I have a draft of the part dealing with urban streets, and I particularly like the clarity given for where different types of cycling infrastructure are required, based on traffic speed and volume, (which is taken from the Cycling Level of Service tool):

We need to make sure that any money spent on transport in Auckland is done in a way that recreates the city in a safer, people-friendly form. To prematurely review the Roads and Streets Framework “because of its emerging financial implications” while the bulk of transport funding – multiple billions of dollars – is going towards increasing road capacity, indicates a reluctance on someone’s part to make the mindshift this city requires.

Councillors, local boards, advocacy and community groups need to get organised to halt this premature review; it’s a battle of mindsets, and has nothing to do with fiscal prudency

Processing...

Processing...

Great post and this Framework is exactly what Auckland needs.

I just hope the same vandals that tried to ruin the RLTP are kept well away from this.

“The same vandals” currently lead AT’s strategy department, and are working to undermine the CEO and Board’s direction, because it does not fit their car-centric attitudes.

I have LGOIMAed AT again to see if they have dumped the 85th Percentile Rule as the US NTSB did

If AT has not and refuses to do so we know they do not believe in change and the organisation needs to be dissolved

Also I see AT are doing consultation on widening Botany Road due to

Yep

Flow

Seems they are learning nothing.

What 85th percentile rule is that?

https://at.govt.nz/media/311063/Glossary_Updated.pdf , the measure of speed and flow

In the part TDM draft I have, the glossary says: “OPERATING SPEED

The prevailing speed of traffic on a transport facility. Typically quantified as the 85th percentile speed (i.e. the speed at which 85% of vehicles are traveling at or below).”

It’s quite inconsistent with Vision Zero, isn’t it?

Yep, hence I have LGOIMAed AT again on it since they said last year they were not going to follow NTSB best practice.

Given their recent consultation on Botany Road was still about flow and speed this organisation has serious problems.

Only if “existing operating speed = design speed” or “existing operating speed = no change needed”

The operating speed is a fact, and there’s no problem with it being defined by the 85th percentile. The question is: Do we design our world based on the Status Quo?

Ok, I got it thanks.

It is standard practice which I doubt will change any time soon. The theory is that if you build a motorway and put up 50km speed limit signs, the signs won’t work. Most people will drive to the speed that the road is designed for. Hence why NZTA seems generally opposed to blanket speed limit changes. We just need to build roads where you can’t actually drive faster.

This rule is basically helping cars and gives us an excuse not to spend money or do anything about actually forcing cars to drive slower.

Actually it was highly discredited by the NTSB – reason why you dump it

AT and NZTA are plain wrong that that they can’t reduce the default speed limits. It has been done elsewhere, without the required change in built environment, and the speeds reduced. And the DSI came down. New York is one example.

Auckland is in the best possible shape to succeed with blanket changes to the default speed limits: drivers here are driving faster for a particular environment than they would in other countries. People here accelerate to as close to 50 on urban streets because they are allowed to, not because it feels right. Drivers buzzing lines of parked cars at 45 km/hr or 50 km/hr would kill a child stepping out from between the cars. The drivers must know it feels wrong, yet they do it because they’re watching their speeds.

With enforcement, default speed limit changes can make a huge change to our DSI numbers. At not much cost. Yes, improved environments that support lower speeds are necessary too, and they can be done in good time.

Yes. People will get used to any speed limit.

We can drop the default limit to 70 or 80, and then have a close look at those few motorways and busy rural roads we have, and decide if we install a custom speed limit. This has already been done; some expressways have a custom 110 limit.

85th percentile was instigated for highway design where it has some logic. Unfortunately,. Somehow it got introduced to urban street design.

The 85th percentile rule was put in Austroads design guides (in Guide to Traffic Engineering Practice) back in 1985, and as that guide got expanded then crossed over into urban road design. It was never really suitable for urban streets. Most of the Austroads design tables cut off at a minimum of 50 kph. Even for highway design, this rule is very dated and is being replaced by other approaches. Speed enforcement was much weaker back in the 1980s.

Likewise the idea of speed flow relationships affecting traffic capacity are even older – originally in the Brittish TRRB research note of 1956(!). They assume people leave a similar time gap between each vehicle as speed increases/decreases. Optimal speed for capacity was believed to be 60-80 km/hr. Modern cars have much better braking than in the 1950s and that view has been proven false. Many jurisdictions have reported no evident drop in road capacity when road speeds are reduced. Here is one of many examples.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0968090X17300396

Is the 85th percentile speed useful at all in analysing an urban street situation? Or is the idea that the environment needs to be built to ensure that people cannot drive above a certain speed? In which case, the top speed possible in the design is relevant, while the 85th percentile speed in the current environment doesn’t seem useful as a design parameter.

We seem to be referring to a definition, not a rule. For rural roads, the 85th percentile speed is useful to design curves so that everyone doesn’t fall off. But setting speed limits in NZ has long used the mean observed speed instead, to avoid a case of “chasing your tail upwards”.

I’m just wondering why it is used as a term, for example, in cycleway projects. Surely not to design anything, just to understand what we’re dealing with?

We design cycleways geometrically to cater for the 85th percentile speed cyclist, eg the average rider might be doing 20-25k but it would be a bit silly if a curve or sight distance constraint on a dedicated cycleway couldn’t handle someone doing 30k as well.

Thanks for that, Glen. And I realised the ambiguity after I posted it. I meant the 85th percentile for traffic. Is that a useful parameter in designing streetscapes to incorporate cyclelanes?

That last graph = Great. Nice and clear What we need to do. The big question now is, of course, just How are we going to get there? Looking forward to reading the Manual and finding out how.

Okay, lengthy piece so I’ll cherry pick a couple of points.

“We need to make sure that any money spent on transport in Auckland is done in a way that recreates the city in a safer, people-friendly form”.

Being a frequent pedestrian you get to see how low priority you are in Auckland. Abysmal to poor condition footpaths is not unusual even in some of the nicer areas, millimetres from fast flowing traffic and often narrow. They are THE first transport route fully closed off around construction sites so Ford Rangers can park up on them, Customs St anyone?

When not in Aucklands CBD It is easier and far quicker to jay walk than await a cross phase at some point in the distant future.

Daily I compete with parked cars, cyclists, restaurants and cafes using footpaths as floor space, wheelie bins, overgrown trees and hedges and anything else you want to dump. I’m guessing the status quo will remain, plagued by not been as not fashionable as cycle lanes!

Secondly cycle lanes. A fortune is being spent such as in Grey Lynn recently but I note, from being a pedestrian, that the separated lanes end up covered with road debris and bikes and punctures go together in these conditions as serious cyclists have lamented to me. There is no cheap way of cleaning them and no one does it anyway. I would not use them for this reason.

To me it kind of undermines the compromise the cycling infrastructure spending is. How is this to be addressed cost effectively because its a real issue and obviously any serious cyclist avoids them if they want to reach their destination in a timely manner!

The biggest eye-opener is taking children around town by bus, with the unsafe walking that involves. I find people who cycle sometimes complain about how awful the congestion is if they do drive (compared to the freedom of cycling). Whereas I usually bus and walk, so the rare times I drive, I am overwhelmed with how everything is set up for my convenience.

Get some proper puncture resistent tyres. Wont help the mamils, they don’t want the extra 200g in weight. I’ve had one puncture in 10 years.

I doubt most cyclists, even with cheap warehouse non puncture resistant tyres, would prefer to mix it with heavy traffic than use a separated lane.

Yes, but Waspman has a point. Debris in cyclelanes is widespread and the cleaning timetable is obviously insufficient. The provision of the cyclelanes is necessary due to the danger posed by motorised vehicles, and the cost of doing so is one more cost associated with driving as a mode. The provision of the protection – which is hindering the cleaning of the cycleways – is also necessary due to the danger posed by motorised vehicles. So it may be costly to keep them clean, but it is a necessary cost associated with allowing people to drive vehicles.

I heard that bike lanes now have a separate maintenance budget. Which was created… simply by redesignating existing maintenance funding, not by allocating new money. Now the maintenance people are unhappy, because they have to do the rest of their network maintenance work with less $$$ than before. Kinda hard to fault them.

There are specialist machines for cleaning cycle lanes, that are common in Europe, I think Christchurch might even have one.

ill take the risk of a puncture in a cyclelane over cars anyday thanks. even if it does take a few min longer. Since i got gatorskin tyres i havent had a puncture anyway.

Thanks Heidi, great post and I fully support your concluding comment: “Councillors, local boards, advocacy and community groups need to get organised to halt this premature review; it’s a battle of mindsets, and has nothing to do with fiscal prudency”.

Yet another Council CCO grand plan, that is being bashed upon the rocks of financial reality.

This RASF document will go nowhere, slowly. The fact that they are raising the financial implications of doing what everyone else overseas has been doing for years, shows how disconnected from reality large parts of AT actually are.

While the Walking and Cycling & Urban design teams might be championing this approach, but its clear the “operations” departments in AT don’t want a bar of it. Hence the financial implications argument for delaying it.

Those opposing factions can’t re-prioritise the RASF below the TDM [which is what they’ve done to now], as the RASF says the TDM is subservient to the RASF. So they attack it on the “its going to be too expensive” front.

This will simply further entrench the “status quo” while

Meanwhile Aucklands competitor cities around the World are actually getting on and actually making a difference for people that live and work there.

20 years years ago a “cars first” plan with a side serve of advanced PT using Light Rail and a underground CRL network might have been enough to compete on the world stage. Nowadays those “nice to haves” are merely just the entry fee to join the game. If you want to succeed you need to deliver way more than that.

AT has been in existence for over 8 years now, and what has it got to show so far? Not a lot really.

“can’t re-prioritise the RASF below the TDM”

Some parts of the new TDM are really, really good actually. Compared to ATCOP, many designs have moved on massively for the better, for safety and active modes in particular.

BUT if the RASF gets “reprioritised”, then the TDM (or at least the common use of the more best-practice design elements within it) will be next to be watered down – we will get a few high-profile good projects, but 90% of the daily work of building new roads and “upgrading” old ones (like those Botany Road intersections) will be car business as usual.

What’ll happen is that private subdivisions will be designed to RASF standards, while major publicly funded projects will be watered down designs. It’s a ‘do as I say, not as I do’ document…I still remember AT insisting on putting in cycle lanes on various low volume roads we were developing (exactly in that mixed traffic range and speed profile above) at the same time they were removing them from the Dominion Road upgrade (where the volume, speeds and likely demand would justify them)

This is a really important post, well done. *determinedly optimistic question

Does the fiscal question suggest that people’s KPIs haven’t been adjusted so they can Do Right and be within budget? Or does the scale of this review show unequivocally that someone has it in for the RSF in a big way?

We KNOW someone has it in it, because behind the scenes, the same people driving this are also the ones agitating against cycling (they managed to cut the business case funding in half, arguing there is no delivery capacity and no public appetite for the whole business case).

Yowch. That’s grim.

Great post will read more carefully later. Think this is a key thought that the general public needs to understand, a lot of whom probably haven’t really considered, especially in NZ/Auckland, they just want to get places fast, maybe want to be near things but don’t want THEIR road or place used much by others (NIMBY type thing really):

“We like nice places, but only if we have access to them. We like to go places easily, but we don’t want to ruin all the places along the way with insensitive transport infrastructure. And if places close to home are lovely, we feel less desire to escape somewhere better, putting less pressure on the transport networks. At every location in the city, there’s a balance between how nice the place can be, and how much it can be a place for moving people around.”

…what I’m saying is they perhaps don’t clearly connect the balance of the two, they just react to what impacts them.

I think you’re right, Grant, and many don’t understand the broader implications of the link between land-use and transport either: sprawl, car dependency, carbon emissions, poor urban form, poor choice in lifestyle and transport options, etc.

Good post.

AT did the same with the old AT Code of Practice, keep it in draft for as long as possible (years) so individual officers can make up things as they go along. We have had narrow slow-speed roads approved by resource consent, only to be rejected at Engineering Approval stage. It is telling that the Road & Street Framework was presented at the recent Urbanism conference by The Auckland Design Office, not even AT! It is part of a strategy that is shown in the Framework, a line drawn between the framework document then the TDM kicks in for the engineers to keep using Austroads standards.

Did anyone also notice the AT publication ‘Local Path Design Guide’ released last year? Written as a sop to the cyclists, some great work, but seems to ignore the coming TDM.

I don’t know if it does ignore the TDM. Would be nice to know. From what I heard, part of the delay for the release of the TDM has been that the cycling part needed improvement, and was sent out of house – to the same people involved with writing the Local Path Design Guide.

Which begs the question of whether we should be using the Local Path Design Guide as a potentially more TDM-aligned document than the interim AT-COP?

And on the matter of the delay – the TDM has now been delayed well over a year. The review of the bike sections only started in ~March/April. The delaying and dithering began long before that.

“AT did the same with the old AT Code of Practice, keep it in draft for as long as possible (years)”

Actually, ATCOP currently STILL is in draft. See for example the cycle section – 5 years later, still has a big draft stamp across it

https://at.govt.nz/media/309960/Section_13Cycling_Infrastructure_Design.pdf

This is just *one* of the crazy things here. They are delaying the replacement for a draft by not publicising the draft of the replacement and now are reviewing it once more, probably to replace it again.

I have worked with the engineers who are leading the TDM document. While they did a bit of a hash of the cycle section (getting all focussed on construction details on how to design facilities while forgetting to clearly identify WHAT types of facilities are recommended), I am seriously feeling that they were trying to do good, and they aren’t the ones trying to slow this down and stop it. It’s their work, they want it out.

It’s the AT strategy department which hates the implications. Because suddenly, they wouldn’t be able to simply add a traffic lane to a signal and call it a day without fixing all the other things wrong about it.

Thanks for all your input here, Damian, and especially for this clarification. I have heard from multiple sources of the high standing and calibre of the engineers involved with writing the TDM, and hope this article can help to save their work from being sidelined. Good to know the reason behind the cycling change.

I don’t think AT ever had any strategy to begin with.

Systematic Safety/Vision Zero, basically?

Just driven along Puhinui Road. Not a cyclist to be seen. What a waste of money creating a cycle lane that nobody uses.

Two lines of paint with parked cars in it doth not a safe bike facility make. Go somewhere else, troll, aren’t there some bridges for you somewhere?

A very illuminating read, thanks Heidi! I sense hours of work and analysis behind this clear, helpful and reader-friendly post.

Speaking of masses of work and analysis, and things we can and can’t afford, and with the clock ticking towards climate reckoning and much else besides: I wonder how many people-hours (and months and years) have already gone into the Framework and the 2000 page (!!) Manual – and how many more there would be yet to come in the review process.

Are we there yet?

Thanks, Jolisa. Add in how many hours went into research and work for AT’s Sustainability Framework, Council’s Parks and Open Spaces Strategy, the Auckland Plan, Local Board Plans, and all the others that are not considered when the RASF is ignored, (and all the implications that has on the ground for a design), it becomes clear that the emerging financial implications of NOT following the RASF are huge.

Great post Heidi

It is a good strategic document that fully integrate land use and transport planning.

Not sure why it took so long to sign off

They may need to have a few pilot projects to kick start it ASAP and learn from mistakes to perfect it.

Thanks, Kelvin. They’ve got some pilot projects in the back of the RASF document. I’m just following up at the moment on whether the lower speed zones got through to the final design…