Everyone loves a good soundbite, so it’s no surprise that the RLB Cranes Index gets more attention than the analysis RLB does to back it up. And hey, cranes are a pretty visible sign of stuff happening, and they’ve been a symbol of construction and ‘progress’ for decades.

I spend a lot of time looking at housing and construction, and it was about two years ago that I wrote “the construction sector is under pressure – there are too many people wanting things built, and not enough builders to do the work… we can’t speed up the rate of building much faster without it causing major cost increases”.

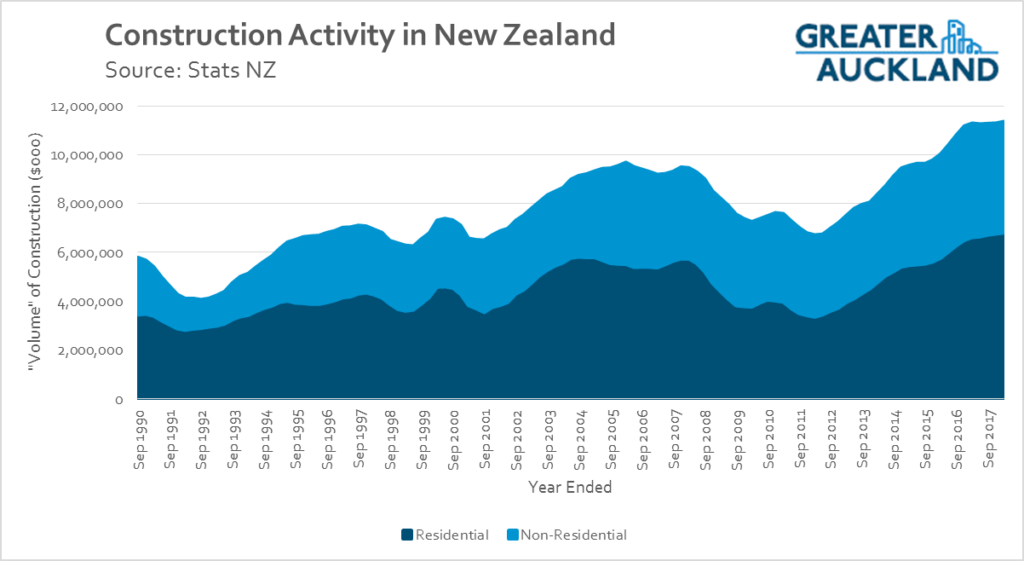

Two years on, we’re in much the same situation. The graph below shows how much work builders do each year, in “volume” terms (covering up to March 2018).

We’re at a plateau, essentially. in the year to March 2018, builders across New Zealand carried out just 0.6% more work than they had the year before. But the cost of building got more expensive – by about 5%.

The graph above shows almost 30 years of data, so it’s worth spending a bit more time on. New Zealand builders had a similar boom/ plateau in the mid-2000s. That didn’t end well. The level of activity dropped by 29% in four years. And then it went up, up up – it’s risen by 69% since the deepest part of the downturn, taking us to record levels.

Imagine how those ups and downs have been for people in the industry, the tradies and the builders and the professions that rely on construction. Many of them would have had a pretty skinny few years after the GFC hit. Many left the industry or even the country. In 2007, there were around 195,000 people employed in construction. That fell to 160,000 during the downturn, and now it’s up around 250,000.

And imagine the logistical challenges in trying to grow at double-digit rates through the last five years, getting people and machines and material to where they need to be. Not easy. How can the industry keep growing when it’s employing record numbers of people but still needs tens of thousands more, or when supply chains are stretched and it’s hard to get the product? Is it just an endless treadmill or is there actually time to innovate, which is obviously what we want?

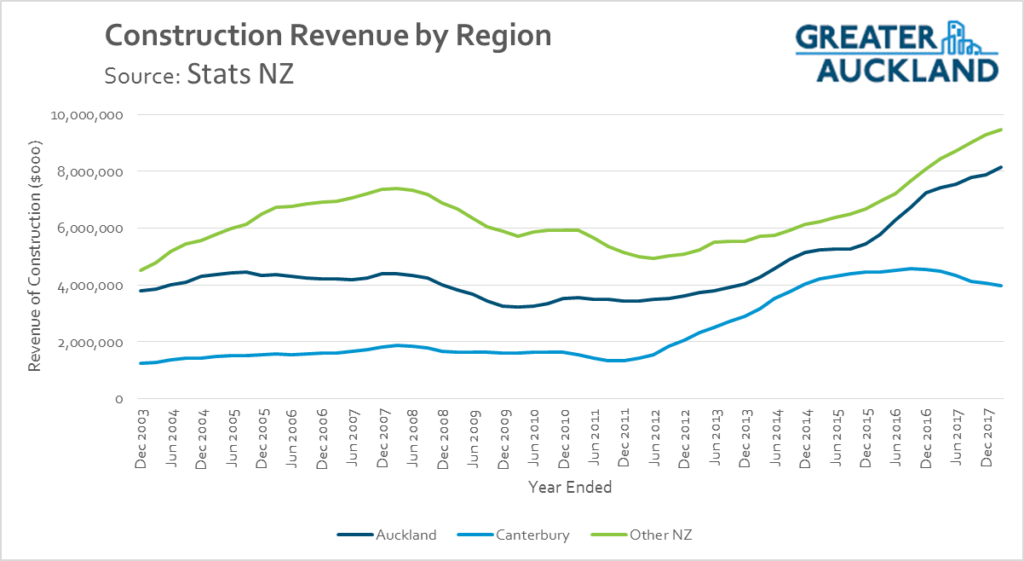

Anyway, let’s move on to the regional picture. These figures are for ‘revenue’, not activity. Part of the growth shown here is due to (hefty) price increases, not just more stuff being built:

Starting in 2012ish, Canterbury started responding to the 2010/11 earthquakes with the biggest building boom the region had ever seen. This boom has been tailing off since 2017, although it’s still high by historical levels.

Auckland is still growing, but probably not by much when you take off price increases. Auckland is both the biggest challenge and the biggest opportunity for NZ builders. The level of construction still needs to scale up further, much further, to make a dent in the housing shortage. But it’s not easy when living costs are high, roads are congested, and you’re competing with other parts of NZ and overseas to get resources in place.

And yet some good stuff is happening. The Unitary Plan passed, Kiwibuild has huge potential, the new government is more focused on housing and looking at the regulation around building.

90,000 Aucklanders are working in construction – some of you must be reading this blog. What do you think? What are you seeing on the ground, what are the prospects, what are the challenges as you see them, and how do we get on top of all this? What about our architects, engineers, developers? What’s going well and what’s not?

Processing...

Processing...

If only the Nats had supported the construction industry during the GFC we would have been building more then, lost less workers, and be in a better position now to build even more.

Unfortunately the Nats don’t have a monopoly on ignoring capacity building. I was thinking about the new Mental Health facility to be built alongside the new prison at Waikeria. The concern was where all the new staff were going to come from when there is already a shortage. I recall the response was that Corrections had a few years to find them. Same problem with Business, too many people trying to find staff, not enough people trying to train and develop them.

That was a big part of what the RONS were about, you may recall, and the associated series of large increases to FED and RUC. That did something for the road sector, but there was no real equivalent mechanism for turning a government tap up in other infrastructure areas – hence the parallel work on a national infrastructure plan and the infrastructure pipeline work.

A previous government of any flavour would have had to have put the work in for National to have had the option of doing what you say they should have done.

I expect, though, that a legitimate criticism was that the RONS as a mechanism got money out the door, but not necessarily in the best way to support broad construction capability across more of the country?

Someone could write a book (or several) about the things holding the NZ construction industry back. I’ll mention two things I think are problems, and how they have multiple flow-on effects.

In residential construction liability rules create incentives to remain small so if you build a leaky building you can just fold the business and set a new one up. The market being almost all small firms creates issues like:

– Insufficient buying power (doesn’t help that the small number of building suppliers operate as a cartel through BRANZ)

– Insufficient specialisation (being a good carpenter doesn’t make you a good project manager)

– Insufficient training of new staff (no time to train people when it’s busy, don’t have enough money coming in to train people when it isn’t busy)

– Insufficient quality control (the only external verification of work is by council building inspectors (assuming they do their job right and assuming the building code is a sufficient minimum standard) so everything gets built to the minimum standard)

– Insufficient risk management (even if you weren’t planning to fold your business as soon as a project goes bad, you probably don’t have the scale to cope with the costs)

In commercial and civil construction large firms dominate because they’re the only ones big enough to take on projects of that scale. However small firms still have a big presence as subcontractors. The problems this part of the industry face mostly come down to government being by far the largest customer in this space (since NZ is a small country). This leads to:

– Insufficient investment in staff and plant (not enough certainty over pipeline of work means there is less investment, particularly in specialised disciplines like tunneling)

– Insufficient innovation (if your biggest client is one government department and they aren’t interested in trying something new, then it won’t happen)

– Insufficient risk management (see Fletcher Construction)

I’m sure there’s other stuff I haven’t read about or considered.

Further to your comment on insufficient innovation, there are some major engineering firms that are also guilty of holding back innovation in New Zealand. There are a couple of engineering companies that between them will almost always either be the designer or owners engineer for large government projects. As such, if individuals at those companies don’t want a new technology the contracting industry cannot invest, as a large amount of work (ie government) would not be able to use this technology. In some cases this is technology with a proven track record of over 30 years. Unfortunately I’ve seen this happen on several occasions.

There are a few large civil firms that train people. But not many. Would be great to see the ones that do recognised.

In infrastructure there is very little incentive to bring on any more staff than is absolutely necessary when the client – who is 95% public sector – award you the job on Lowest Cost Conforming bases. Cheap wins the job, and that includes wages. Unattractive.

The government’s changes in housing and infrastructure are a massive policy U-turn compared to the previous administration, so there is a great gaping hole in most firms order books while NZTA and AT etc sort themselves out. So there’s little incentive to hire until there are actual jobs to win and hire people for. Also unattractive.

The government is sending pretty odd signals about how much it will enable the big firms to import, and how much it will support locals into the workforce. To do that they have to award the jobs with more money, or those jobs aren’t going to pay to be attractive at 4% headline unemployment. So you get what you pay for.

Even the largest civil jobs in New Zealand struggle to attract international attention, and we are only slightly more attractive to specialists than Oman or Ouagadougou. So it’s common for specialists in piling or tunnelling to get poached offshore.

This is going to get a whole bunch worse.

The points about finding international workers (and professionals) to help are important, I think… stay tuned for another post soon, showing that Australia is in a similar boom and also trying to source international workers, making it that much harder for us…

So if the lovely two-tone blue chart of construction activity has a marimekko pattern regularity to it, we can expect that the construction to dip again in, what? 2021?, unless we change how we do things.

What about shifting more of that work to the public sector now? Then when the dip comes, the public sector can continue on with construction, for the common good of keeping the skilled people employed until the next boom, and getting some of the backlog of work done, despite market forces not stacking up.

The construction sector in NZ has always been a very cyclical thing – boom and bust, pause to regroup, then boom and bust again. Traditionally that has been about a 7 year cycle, but recently the cycle has been getting longer. From the graph above you can see the 90s boom – starting from a low point in 1992, building up and booming and back to a slump in 1999. Seven years. A curious little mini-blip then back to another boom and bust from 2002 to 2009. Another seven years. But we know what happened then: the GFC meant that the global supply of money ran out. So, not that there was no demand for building – more that there was no supply of money.

The current boom has gone on strongly so far, and looks like we may break that 7 year itch. Barring any external event like another war in the Middle East or in China (with Trump in charge, anything is possible – he’s already started trade wars with damn near everyone) and given the pump-priming being initiated by the new government, there is no reason to expect that the current boom which started in 2012 will finish by 2019, and it may sustain for some time longer. Unless, of course, we run out of demand (i.e. if immigration falls off) or if we run out of a supply of money, either internally (i.e. if government stop writing cheques) or externally (i.e. like a GFC 2.0).

I’m very wary of attempts to extrapolate the past into the future. It’s true that the natural way of things is to go up and down, a ‘cycle’ if you like, but no cycle is the same and they can be really short or really long. Still, at some point there will be a downturn.

You’re quite right that the public sector can smooth out that process, and that’s part of the rationale behind Kiwibuild. When the industry is gangbusters like presently, it will be hard for Kiwibuild to have much of a ‘net’ increase, but people will be grateful for it when a downturn hits – and Kiwibuild delivery will probably speed up during that part of the cycle.

And as another commenter said above, this was part of the rationale for the RoNS too, although those took so long to get going that they didn’t really smooth the curve at all. And the funny thing was, Nick Smith was resolutely opposed to applying the same ‘smoothing’ idea to housing. He was still resisting that in 2016.

Some economists would argue that the government shouldn’t get involved in this ‘smoothing’ thing, at times when the private sector wouldn’t want to invest. My view is that it’s desirable up to a point; it shouldn’t be an aim to eliminate all ups and downs. But during the downturns the government can get better deals from builders, so especially for assets it’s planning to keep (social housing, infrastructure) why not bring their construction forward?

Buying infrastructure during downturns requires two changes to how our governments work. Firstly it would require long term planning. Currently projects are planned to achieve soundbites at the next election which at most means a three year plan. Bringing something forward only makes sense if it is something that was actually needed.

Secondly it requires our governments to change how they think of money and value to something closer to how the private sector thinks about money. A private sector investor with cash will use the market price as a signal or trigger for investment. If the price is low they will buy more. Governments just don’t work that way. Our governments value things based on their price. To the government a $1billion project is more important than an $800 million project. The press and public aid that nonsense. Just look at Shane Jones’ development fund. The question the press is asking is can he spend it all, not will he buy anything worth $1billion?

In some ways it is worse.

There has been work to develop a pipeline of projects, but then people look at it and decide to pull everything with a big price tag forward.

And then they worry about the gap that creates and the uncertain message it sends to industry about the stability of the capacity requirements into outyears…

As a land surveyor we are one of the first with new developments with the topographical plan, boundaries etc for concept /design. From what I have seen there is still significant amount of development in the pipeline.

As for construction survey setout we have been flat out for the last 4 years with the obvious issue of finding suitable staff. Boom times.

However having worked in the construction industry since 1983 when the tide turns it can be a hard industry to be in.

Impressed by how much work continuing in Christchurch.

Interesting to note the project engineer showing Matt and I around the CRL site made a point of praising the quality and speed of the work of the Filipino crew… I mentioned this to my architect brother in Melbourne; he said, funny that, all our sites are full of Kiwis!

The level of building in Christchurch has held up reasonably well so far, but that’s largely due to projects taking longer… it’s likely to slow down into 2018, 2019, 2020. Looking at building consents – an indicator of future activity – they’ve dropped by a third in the last three years, and are still falling. In another 2-3 years, they’re likely to be back at pre-earthquake levels. Maybe lower, if there’s a supply overhang.

The construction industry globally has been one of the least productive for decades on end. In fact by some metrics it is less productive than it was in the 1960’s. They are building less stuff, more expensively. Most innovation that has happened just comes with increased costs,but little added value.We are essentially building stuff the same way we did 100 years ago.

Pretty much as has been mentioned here.

Small companies that disappear, harsh economic cycles that reward small companies and punish a heavily capitalised innovator, conservative building standards and conservative customers all make innovation really difficult.So we remain stuck.

Agreed. Your comment makes sense and to be fair so all the other comments. I just hope some politicians are reading.

Your last paragraph made me think; how can it be avoided? Much as I hate socialism Heidi’s more govt involvement makes sense to me – the old dept of works used to work; just call is ‘kiwibuild corp’. Generous rewards for employing apprentices – that woud give medium sized businesses a financial buffer. Universities get substantial govt funds for producing a flood of business and commerce graduates so why not businesses that produce qualified plumbers, brick-layers, plasterers, etc?

+1

Nice to have you back, Bob! 🙂

NZ tried having non-conservative building standards, that led to leaky houses being built in the mid-2000s. In addition construction standards were so bad that higher levels of documentation and certification for builders was required. Unfortunately if the building standards are loosened, we will see very poor construction, again. The higher standards don’t fix all the problems with the quality of the industry, but will reduce the problems.