A few weeks back I was fortunate to be a guest on a university study tour of the Netherlands with Peter Koonce and Peter Furth. I posted a video on Dutch Systematic Safety by Peter Furth a few months back. Professor Furth has been leading study tours of the Netherlands for American transport engineering students for over a dozen years. I’ll be writing a bunch of posts on the interesting things I saw and learned, in particular the things that are relevant to Auckland/NZ.

To start off, here is a post on Houten. Located 10km from Utrecht, Houten is a bedroom community designed by Robert Derks during an era of focused greenfield development under the government’s urban expansion plan of “concentrated deconcentration”. It was designed from the beginning to be a place where people could walk and cycle for their daily needs and to live within an easy bike ride (1km, 8 minutes) to the train station.

The design of Houten began in 1968. It evolved because of several events. First it was a rejection of the growing car based modernism (CIAM). There was also the oil crisis of 1973 and a historic high number of traffic fatalities in 1971. To make the city safe for cycling, the city was designed with two distinct street networks – one for cars, and the other for walking and cycling. People walking and cycling have a dense network of paths and streets, the car network is confined to small catchments served by a distributor ring road. These small catchments of housing can only be accessed by the ring road. By design, local trips to friends, shops, and the train station are closer by bike than by car. Local trips outside of people’s immediate neighbourhood require a circuitous journey via the ring road.

Carefully prescribing vehicle routes is now common practice in many Dutch cities. Many of the city officials and professionals we spoke to were actively re-organising street networks to improve safety and residential living quality by limiting and redirecting through traffic. I’ll write more on this in another post.

Houten is a remarkable example of how greenfield development can successfully create conditions that support non-motorised transport. Because of its dual street structure and the availability of high quality rapid transit, it is somewhat difficult to draw lessons for New Zealand. The one thing I think that is particularly relevant is the comprehensive application of traffic calming techniques. Let’s just say they don’t just post 30 kph signs.

Drivers access specific neighbourhoods via a 90kph distributor ring road. This road is exclusively devoted to traffic flow, so there are minimal access points and few intersections. Because of this, it only needs to be one lane in each direction.

The entrance to each neighbourhood is marked by larger buildings that form both a landmark and gateway feature. What follows is a series of design interventions that require motorists to snap out of their motorway trance and become aware of their new surroundings.

The first trick is that the entry roads are short, no more than about 40 metres. Immediately after entry, the road has a lateral shift – a curve or a turn.

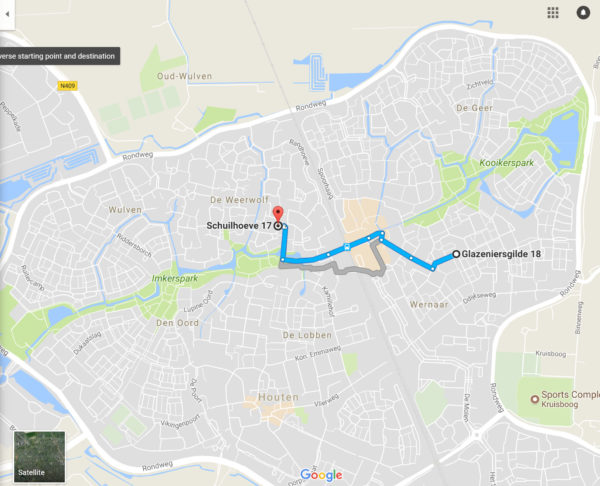

Using the example from the Wernaar neighbourhood accessed by De Akker, drivers are forced to make a sharp turn. Forward vision is limited by trees. Trees are also located close to the street’s edge further narrowing the drivers’ field of vision and adding a degree of side friction.

After the deviation, cars are channelised into a narrow lane. The first intersection is marked by a raised-up intersection, the introduction of pavers, and for good measure, a 30kph speed limit sign. The intersection is also uncontrolled so a car coming from a different direction remains a possibility. There are no lane markings.

Past the first intersection there are a web of short streets that serve as lanes, and car courtyards. While very narrow, little more than 4m, most of the streets are shared in both directions. The blocks are very short, with sideroads every 50 – 70m. When the streets cross a main bicycle routes, drivers are slowed again with speeds humps and priority (for cyclists) markings.

By slowing traffic so quickly and effectively, the entire neighbourhood becomes a pleasant place where people can live peacefully and children can roam widely. While the street network seems denser, and potentially costlier from a development perspective, the road space becomes multi-purpose- serving in sections as main cycle routes and in other areas as courtyards and front yards.

It’s baffling to me that designs like this haven’t universally taken hold except in some resort settings. Also, why aren’t these traffic calming techniques more widely understood and applied in the Anglosphere?

Processing...

Processing...

“it is somewhat difficult to draw lessons for New Zealand” → It’s not like they don’t do greenfield developments around here. A prime candidate for this kind of plan would have been Millwater. Maybe that’s too late but I’m sure it won’t be the last development of its kind.

But yeah it starts with the street design. “While very narrow, little more than 4m, most of the streets are shared in both directions. The blocks are very short, with sideroads every 50 – 70m.” When was the last time AT built a street that small? Also note how these streets are cycle-friendly despite the lack of cycle lanes.

To be fair Millwater is quite well designed and is more pedestrian-centric than most New Zealand development. It is just a shame the car still dominates

“a shame the car still dominates” That’s a good indication it’s not really well-designed.

A difference between Millwater and Houten is density, which you can easily see if you compare a map of those two developments side by side:

https://acme.com/same_scale/?52.02865,5.16029,-36.60590,174.66815,17,H,H

The footprints of the houses in Millwater are huge! (and due to the Mercator projection used by Google maps, Houten is shown at a slightly larger scale)

As a consequence, from any given point you have a lot more houses or businesses within walking distance in Houten. Note also the length of the blocks.

Millwater is not built to human scale, i.e. things are too far apart to be walkable. You can walk around, but there’s just not much interesting to see within walking distance.

Bicycles could level that difference somewhat (contrary to popular belief you don’t need an entirely flat area to ride a bicycle). But whether that is feasible or not mainly depends on how fast cars drive over there. Which I guess is 50-but-actually-60 km/h, so that’s going to be a ‘no’.

A thing to note about cycling here is the treatment of on-street parking. In Auckland there’s usually no clear distinction between parking space and the rest of the roadway (and often both cars and bicycles weave in and out between parked cars). In contrast, there’s often a clear distinction in Houten. There’s exactly 0 expectation that cyclists swerve between parked cars to let cars pass.

And so on — there’s probably a hundred small or larger details which conspire to make most areas in Auckland car-only.

Thanks Roeland. I was going to say that Millwater may have pedestrian amenity but it is certainly not walkable. But your reply was far superior. Great photo comparison.

Love it. But I guess here too many love their cars.

Some people in Houten love their cars too. There are 415 cars per 1,000 residents. The main difference I think is that they don’t use cars for every trip.

While some people certainly “love their cars” A lot of people simply haven’t been given much choice. Reading this post it struck me that this idea sounds revolutionary a complete paradigm shift from the car-centric/dominated world I have grown up in, in Auckland.

Houten was designed so you wouldn’t need a car. Most subdivisions in NZ are built such that it is almost impossible to commute to/from them or even to get to the nearest shopping centre without a car.

They used to love their trams until the powers that be decided we couldn’t have nice things. With zero consultation with the community.

I really like the idea. Not too dramatically different to Welwyn Garden City (or the bit where my Aunt lives) but newer. Like the roads. Like the cycleways. Like the sensible trees – shelter in the cold and shade in the summer and no obvious roots distorting the footpaths/cycleways. But prefer my stand alone weather board house to these apartments. That’s is why I don’t live in UK/Europe.

They should be using this kind of design for a new Kumeu suburb – that is if there was a high speed train or busway from Kumeu to the CBD.

Wonderful to see these examples, thanks Kent. I can see many ways these ideas can be used to retrofit our suburbs. We just need the political will.

I was in The Netherlands a few years ago, and when I returned I suggested we (NZ) quickly grab some Dutch town planners to manage our Christchurch rebuild. Even Auckland should consider this model, since we also consistently fail to take advantage of Greenfields opportunities. I’ve been in the New Flatbush development a few times recently and I just shake my head. Trust me, the Dutch have it sussed.

I have family in Bergen (I’m going back in Sept) and there it is very much as you’ve described (and photographed) Houten. The Dutch do all have cars, but as you say they don’t use them all the time. Part of that is due to it’s flatness which allows everyone to ride a bike easily (which in itself becomes a habit, meaning even 70+ continue to ride) and part of it is the good PT – but the main part is the excellent town planning. You really feel like you are living in a community, and everything is handy via walking and cycling paths.

I look forward to your follow up articles Kent, because it’s been hard to articulate what I saw on my last visit. As I said, the Dutch seem to have it figured out (including Medium/High density living – don’t get me started on that!).

While something like this could be the long term plan, I still think the best thing we can do right now is to lower the speed limit to 40 km/hr in residential streets (or lower). The cost is minimal, it could be implemented in a matter of months with political will, and unlike most other countries, NZers tend to follow speed limits due to a high level of policing and speed cameras.

I really don’t think speed limits work too well, nor all of the roadside signs of various designs promoting attention, care, etc. I frequently find I’m driving along and I suddenly wonder whether the speed limit has changed and I’ve missed the sign – the roads themselves don’t provide any cues. I also find myself resenting many speed limits as the road is clearly designed to enable higher speed travel and they feel safe at higher speeds – partly because no-one but fast-moving cars ventures to use them. It’s not a recipe for success to post a speed limit that feels too slow and engenders frustration in the driver (and the driver behind the driver). As a pedestrian, cyclist and parent, I appreciate the benefit of the lower speed, but as a driver it is frustrating to the point of distraction to be given a fast-looking road with a slow limit.

By the same token, I find I don’t resent slowing down on windy, narrow roads with trees, which are shared with non-vehicle users. I would feel unsafe going faster and feel content driving at the slower speed, paying due attention. My response to bends and trees is not to resent them, but to respect the constraints they are imposing.

These sorts of roads are self-explanatory:

http://www.futurestreets.org.nz/self-explaining-roads/

https://ec.europa.eu/transport/road_safety/specialist/knowledge/road/designing_for_road_function/self_explaining_roads_en

https://www.pps.org/blog/what-can-we-learn-from-the-dutch-self-explaining-roads/

Clearly, there are levels of skill in the design and implementation which can make these aspects of road design more or less obvious (or less or more natural feeling). My contention is that the more natural the designed-in constraints feel, the easier it is for the driver to accept (consciously or unconsciously) and drive accordingly. Signs are the least natural and consequently hardest to accept methods of restricting speed. And you can miss the signs or forget yourself, whereas the road is always there, subtly directing your behaviour, without nagging you.

NB when you have self-explaining slow roads, you also have self-explaining fast roads. It’s not just about slowing down, it’s about different roads having different functions and communicating those to the users.

That pps.org link is interesting thanks, comparing changes done in safety between the Dutch & the US.

On the flip side, though, it’s really frustrating when a residential street feels like it should be slower, with perhaps some planter boxes and trees and sleeping policemen put in to slow the cars, but AT won’t post a lower speed limit. There are enough drivers out there that carefully enter the road at a low speed and then accelerate. I think widespread lower speed limits should come in along with changing the rule so turning cars have to give way to pedestrians crossing side streets, and the replacement of courtesy crossings with pedestrian crossings as part of a huge campaign to change the way drivers drive. Done all at once with a huge education campaign the expectation on drivers to change will be high.

Many pedestrian crossings have been taken out in our area and been replaced with courtesy crossings (Pedestrian refuges?) . Also crossings removed from areas of high demand and moved several hundred metres up the road this results in people trying to cross the road in busy traffic.Overseas they would fence off the road or put in an over or underpass.

Can you tell me the places the pedestrian crossings have been replaced with courtesy crossings or pedestrian refuges? Some time I’m going to look into all this.

It’s great to see examples like this to see the stupidity of full pedestrianisation and the effect it has.

The word that comes to mind when reading this article is “inefficient”. By eliminating quick and easy transport options such as direct vehicular access, performing simple tasks such as visiting a supermarket or a mate take an unnecessary long amount of time. You either piddle along on your bike at 20kmph or go via Amsterdam!!

No 90kmph road should be single laned. Again it’s terribly inefficient as everyone has to go at the speed of the slowest driver. I’m sure that appeals to the anti-car mob that hangs out here but in the real world the result is slower transit times and an increase in vehicle emissions.

The third point to note is the housing required to make this whole arrangement “work”. Houses have to be built on top of one another where no resident has meaningful space to themselves. Kicking a ball around in the back yard? Forget it. You couldn’t even swing a cat around these properties. This is the sort of open the window to touch the neighbours house crap which is the antithesis of what it means to live in New Zealand.

This town is a good example of how not to do transport and provides an excellent case study as to why a multi-modal model provides the best outcomes.

Yes there is no where to kick a ball around unlike our developments like dannemora https://www.google.co.nz/maps/place/Dannemora,+Auckland+2016/@-36.9305522,174.9201672,901m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x6d0d4b5ed9e9223b:0x500ef6143a2bee0!8m2!3d-36.9292773!4d174.9222711 where they can play cricket in the back yard unlike Houten where there are no green spaces https://www.google.co.nz/maps/place/Houten,+Netherlands/@52.0288024,5.1612658,1386m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x47c6673eb235f455:0x4acab4fdc3a3e0a6!8m2!3d52.0029907!4d5.1857599

Note the same scale

And even with these horrendous living conditions, the Dutch still manage to perform very well in sport. Plus of course having the 2nd happiest children in the world (after the cycling Danes).

When I was in Amsterdam last year, I saw a lot of young people cycling to sports with their football boots/hockey stick on the back of their bike. I learnt most of my sports skills down at the park or at training (also in a park).

This romantic myth of kids learning ball skills in their back yard is just that, a myth. Sure Dan Carter learned to kick in his backyard, but that was an entire paddock with a rugby goal post – not a suburban section that 90% of Kiwi kids live on.

We really need to put some of the these “Kiwi” myths to rest so we can move on and discuss how things work in the real world.

Troll much? You have such a strange way of looking at the world, Matthew…

Exactly. The same antagonistic – and increasingly strawman – arguments.

On the bright side, his mum lets him leave the dinner table with a bit of time before bed to post stuff like that.

The thing is, if you piddle along on your bike at 20kmph in the Netherlands, you’ll probably arrive at your supermarket faster than when you’d drive your car to the supermarket in Auckland.

Nowhere in Houten is more than 2km from the central shops. So even if you were “piddling along” at only 15km/h it would still take you no more than 8 minutes to get there by bike (and you don’t then have to spend further minutes trying to find a carpark).

But this town is multi-modal especially compared to most places in NZ.

The biggest difference between the multi-modal model used in Houten and what we do in NZ is that Houten has been designed to make PT and active modes of transport as efficient and safe as possible to a small detriment to car travel.

Where as in NZ we make car travel as efficient as possible to the detriment of PT and active modes.

The problem is a car is the least efficient means of transport in terms of cost and space. And if too many people try to drive at the same time then it is the least efficient in time as well.

So why are we pouring most of our resources into what we know to be the most inefficient means of transport which also by the way kills and injures people?

“This town is a good example of how [extra word deleted] to do transport and provides an excellent case study as to why a multi-modal model provides the best outcomes.”

Fixed it for you.

Just hard to know where to start with this nonsense. Basically take everything written there, reverse it and you are much closer to reality.

The empirical outcomes from Houten (and other Dutch cities) completely contradict your view.

What people on this blog need to understand is that we all want a 1/4 acre section with a tree to hang ourselves from and an exceedingly wide road to fire our Audis along, so we can kill our neighbour’s kids and reach the gold standard of 400 dead a year on our roads ;-)…not much to ask

Your comments are getting a bit gruesome now. Can’t we go back to the colour of your audi and if you really wasted $60k on it?

Sure Heidi, to be honest it actually cost $40k, $1 for every dead New Zealander on our roads since 1950, and it’s coloured brown as I drew it on the wall of my padded cell with the only paint I had available, they committed me after they found me bashing my head against the tiled wall while waiting eternally for the Hamilton to Auckland express train at the beautiful central city underground station….;-)

Auckland, until recently, has been a good example of how not to do transport and provides an excellent case study as to why a multi-modal model would provide the best outcomes.

Multi-modal = not putting 95% of transport funding into roads, which is historically the way it has been in NZ cities.

The title of this post was ‘slowing drivers’; the other interesting thing in Houten is that they also slow down the motor scooters that are allowed to use the cycleways as well. Approaching intersections of paths, it is common to see ‘drempels’, i.e. a series of wavy speed bumps that are uncomfortable if you try to scoot over them at speed.

Oh yeah, those were interesting. I also saw them on some cycle super highways.

Drempel is a very nice word. Better than Speed bumps. Or, as they say, unfortunately, in England, a sleeping policeman.

Question: If the residents in a dead-end street decided they want to park in one third, and keep the other two thirds as cycling / walking / playing space, would AT let them? Obviously they’d need to let in the odd delivery of bulky items, so a complete depave wouldn’t be possible.