I’ve recently been taking a look at Statistics NZ’s Census data on car ownership in Auckland. One interesting observation is that low-income households are considerably more likely to not own a car. One implication is that minimum parking requirements, which require everyone to have carparks (or pay for their provision every time they go to the shops), are a quite regressive policy. (More on this in a future post!) And, of course, providing frequent, reliable public transport services and safe walking and cycling options throughout the city will benefit low-income households the most. (In other words, separated bike lanes are not just about hipster urbanism!)

Another interpretation of the data on car ownership is that it shows that a car is what economists call a “normal good“. In plain English, this means that when people’s incomes increase, they tend to have more of them. This seems to be true in Auckland: high-income households are less likely to own no cars and more likely to own three or more cars.

However, people commonly assume (or assert) that public transport is an “inferior good“, or something that people consume less of as their incomes increase. This assumption is deeply embedded in transport policymaking and transport modelling. It’s part of the reason that policymakers have been so eager to disinvest and underfund our public transport networks over the past half-century: “In the future, we’ll all be richer and drive more.”

But is this actually true? Let’s take a look at the data.

First, I took a look at the Household Economic Survey data, which Statistics NZ has very helpfully broken down by decile of household income. Here’s a chart showing the percent of household spending that goes to transport (including cars, petrol, public transport, etc) and passenger transport alone:

In short, higher-income households do seem to spend more money on passenger transport, both in absolute term (i.e. dollars per week) and as a share of their incomes. This may suggest that public transport isn’t an inferior good. Unfortunately, though, it’s not possible to draw any definitive conclusions from this data for two reasons. First, the Stats NZ data doesn’t allow us to split out urban areas (where average incomes tend to be higher and PT is available) from rural areas (which tend to be poorer and lacking in PT). Second, Stats NZ has grouped air travel into the passenger transport category… which means we might just be picking up the fact that richer people fly more.

So let’s take a look at a second set of data: 2013 Census data on household incomes and main commute mode. To avoid issues with comparing between rural and urban areas, I focused on data for Auckland alone. The following scatter-plot shows the correlation between PT mode share for commute journeys and median personal income for Auckland area units. (I’ve excluded area units with population densities less than 1 person per hectare, as they’re likely to be rural areas where PT isn’t available.)

There isn’t much of a pattern in this data. There are some higher-income areas with high PT mode share, and some with low PT mode share. But the trendline does seem to be moderately positive. In other words, the Census data doesn’t seem to indicate that PT is an inferior good – people in higher-income areas are slightly more likely to use PT.

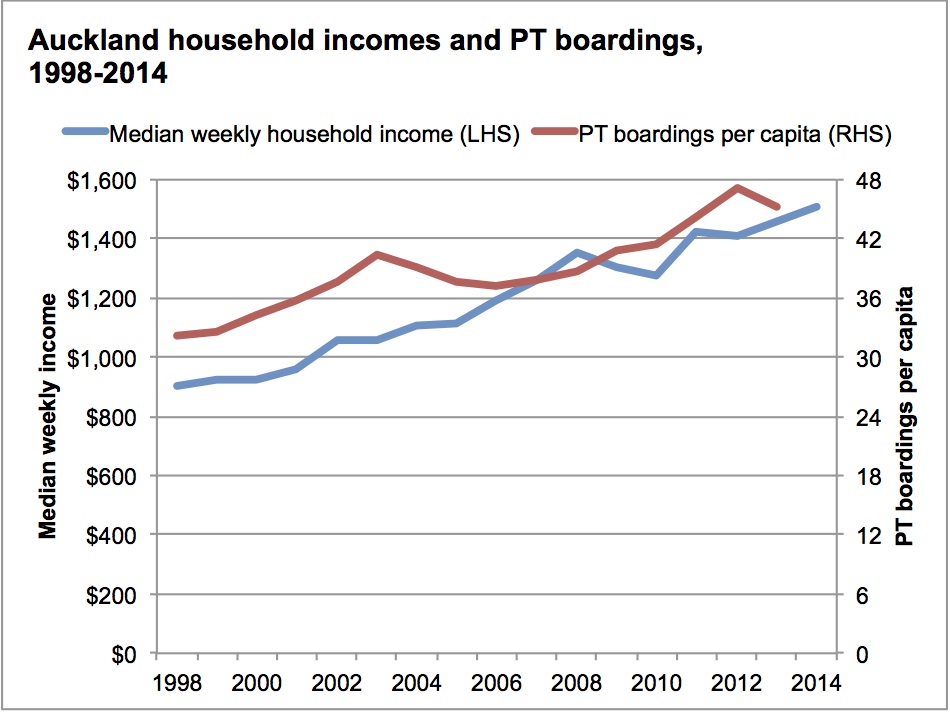

Finally, it’s worth taking a look at changes over time. In other words: Are Aucklanders using PT more or less as average incomes increase? In order to examine this question, I looked at Statistics NZ’s data on household incomes by region as well as the public transport boardings data that Matt has diligently compiled. The Stats NZ data only reaches back to 1998, so we’re limited to looking at recent changes.

Matt’s data on patronage shows that total PT boardings in Auckland rose from 37.6 million in 1998 to 72.4 million in 2014 – significantly outpacing population growth. Incomes also rose over the same period. Here’s a chart comparing changes in (nominal) median household incomes with changes in PT boardings per capita for the Auckland region:

In recent years, Aucklanders haven’t reduced their use of public transport as incomes increased. In fact, we’ve seen the exact opposite – PT trips per capita have risen in line with median incomes. (Or even slightly faster, as I didn’t account for the effect of inflation on incomes.)

Is this conclusive evidence that PT is a “normal good” that people will demand more of when they get richer? Probably not – I don’t have the time, budget, or micro-data to analyse the behaviour of individual transport users. But it provides no empirical support whatsoever for the assumption that PT is an “inferior good” that people will want less of in the future.

In short, we should probably stop simply assuming that PT use will wither away with rising incomes. That might be true, but it’s not obviously apparent in the data. A better course of action would be to start planning to provide public transport that will be useful to people of all incomes.

Processing...

Processing...

Can you give us statistics on PT use based on household makeup – eg do families with children use Pt more or less than single people or retired people? I suspect people would use cars more as their families get to school age, because a car is often necessary to get kids to school, sports, friends’ houses, grandparents etc. If you have a car, then it’s a lot easier to transport your family all over town to various appointments. I know my children missed out on some things because I can’t drive and there was no bus.

Hi Pam – interesting question! Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like the publicly available sources – e.g. the Household Travel Survey or Household Economic Survey – publish useful breakdowns of travel behaviour by household type. I guess a custom request to Stats NZ would be needed.

I also think you make a good point about how having better transport choices is especially important for kids. Not being able to drive in a car-dependent city means being stuck in place…

Hi Pam ( and Peter,)

There is a public table derived from the HES that allows you to look at spending by household composition and number of dependent children, and it includes the transport group and sub groups,

it is here

http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLECODE7556

But the quality of the date is not great ( as indicated by the *) , but at least it is something,

Yah, I took a look at that – the issue is the fact that air travel has been lumped in with “passenger transport”. A custom request would be needed to net that out.

Might be possible to use Census data on household composition to make some inferences, though.

I got curious about this. (An occupational hazard.) Some very back-of-the-envelope regression analysis of Census data suggests that:

* Suburbs with a higher share of people living alone tend to have higher PT modeshare for journey to work trips

* Suburbs with a higher share of people living in one-family households tend to have a lower PT modeshare for journey to work trips

* The share of people flatting or living in multi-family households didn’t have any statistically significant effect on PT modeshare.

So this would seem to support your hypothesis. However, the model has very little explanatory power – it accounts for only about 8% of variation in PT modeshare throughout the city.

The implication, I think, is that while household composition plays a role, other factors like the quality of PT options available to people will have a much greater influence on modeshare.

I often wonder about how kids get around in here as well. Ideally for shorter distances kids could just ride their bicycle. But yeah, unfortunately…

Hi Pam, that analysis is possibly but would require the purchase of a customised dataset from Stats NZ which crosstabs household type with PT use. You got a spare $230?

“a car is often necessary to get kids to school, sports, friends’ houses, grandparents” – But let’s remember that is only a relatively recent development. Until the early ’90s kids were nowhere near as dependent on their parents.

I am 40 and had one friend growing up who’s mother wouldn’t let him ride a bike or take the bus. So he had to be driven everywhere and it was a real pain if you wanted to go anywhere with him. We all used to talk about how weird it was.

Now I would be the weird one for wanting to cycle or take the bus and he would be the “normal” one. Sad time to be child in terms of freedom and independence.

Children’s lives also used to be less complicated – mums at home so no need for after-school care; not as many after-school activities; families might have lived closer to each other (or the grandparent died younger?); bigger families so the older kids could mind the younger ones? I wonder if a lot of the advocates of “ditch the car and take public transport” maybe don’t have families? Commuting to work is one thing, but doing a lot of other things without a car is a pain and that should be acknowledged. On the other hand: my daughter’s intermediate school was 15-20 minutes away. Most days she would walk to a friend’s house and then they’d walk together. On rainy days the friend’s mum would give them a lift. One rainy day the friends’ mum rang me to see if I would take the girls to school. I can’t drive. I said it was fine, my daughter had a raincoat and would just walk. The other mother was aghast – “they’ll get soaked and catch pneumonia!” So yes, there are some over-protective parents out there.

On the last graph, the 2014 result is slightly above the 2013 one and by the the end of this financial year (June) will likely be 51 or 52 based on current trends

Cool! Going from 35 trips per capita to 52 in 17 years is actually a huge accomplishment – effectively a 50% increase in PT use.

As we have become “richer” we bought a house close to a train station and take public transport a LOT more. The economists need to update their models. Cities like Toronto are a good guide. One of the reasons homes in the city rise in price there is the better access to public transit and shorter travel times by any mode, but especially via public transport.

Exactly. And also telling that homes miles from public transport are much cheaper.

That is one of the things you see with cities like Houston and Atlanta. I once looked up one of the McMansions being promoted as the model for NZ to see what the PT options were.

The first direction on Google Maps was “Drive 5 miles to the bus stop”.

Marginally off topic, but a very interesting read none the less.

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/apr/28/end-of-the-car-age-how-cities-outgrew-the-automobile

That’s a great article!

Good post Peter. It’s little assumptions like this that seem to litter the transport and political realms that net to be confronted

We see the same implicit assumptions still happening in transport and political realms.

As follows, 3 are from earlier decades, one is current, see if you can work out which is which:

“Soon we will all have flying cars/jetpacks/helicopters, so the roads won’t be as congested. Therefore we should reduce or delay any future PT investments as a result.”

“Soon we will all be working in a global village so won’t need to travel into a big city every day for work, we will simply work from near where we live.”

“Soon we will all have cheaper imported cars, so we won’t need to have the kinds of bus and train services we have now. So we should stop investing in buses and trains.”

“Soon we will all have driverless cars so the roads won’t be as congested. Therefore we should delay PT investments until then.”

2 and 4 are both current

don’t forget: ‘endless cheap oil/our own Saudi Arabia any minute now off the coast Taranaki/Canterbury/northland… somewhere somehow at no cost’

I think the background to the assumption has always simply been that there was strong evidence that car use was a normal good. It was reasoned that cars and PT were substitutes so within a fixed need for travel PT must be an inferior good. But of course if increasing incomes means more travel in every mode then they can all be normal goods. But as you say you need micro data as it depends on whether an individual person will use PT more if their income rises. That must be true for people in the central city.

Is there actually strong evidence for car use being a normal good? Peter talks about car ownership being a normal good, but that’s quite different to car use.

My baby-boomer Dad always talks about buses only being for poor people, but from my time living in Wellington it definitely seemed like the complete opposite. The people using public transport seemed to mostly be CBD workers on white-collar incomes, while those using their cars more were the ones who worked out in the industrial areas or on-site on blue-collar incomes.

I recall when living in Wellington 20-30 years ago, I’d read the Evening Post and see its “People in Business” section, 2-3 photos and very brief bios of lawyers, stockbrokers, bankers etc and think “I’ve seen them on the bus from Karori”

even today, about a half of the people catching the 802 express from Bayswater either wear suits or creative trendy casual

so loser cruiser? don’t really think so

Is public transport an inferior good? It depends on the circumstances. Definitely not for the stockbrokers who pay high fares to commute to London on fast trains. Probably yes for poor non-car-owners in car-dependent suburbia with ‘last resort’ bus services. And varying answers for all the other possible circumstances in between.

But what is the significance of the answer, anyway? If public transport is an inferior good for some people in some places, that does NOT mean that it’s valid to say, ‘predicted growth in average living standards means that public transport will be less needed in future.’ In the last few decades of growing inequality, the non-car-owners in car-dependent suburbia are the very people, the bottom quartile, who have not shared in the AVERAGE growth in real income. Their transport needs still exist and will likely continue to exist.

Hi John – thanks for commenting! You raise some really important points. It’s really easy to concentrate on _average_ outcomes and ignore the vast diversity that exists in people’s preferences, living situations, and incomes. A solution that works well for one person may fail horribly for someone else.

As I’ve written in the past, transport agencies need to recognise that not everyone is an “average” user, and providing people with a range of transport choices that can fit different preferences and budgets.

An inferior good is, as you say, a lower quality good, typically consumed when income’s are lower. I have an average income and a car and travel by trains feels to be a luxury. I do not have the stress of driving and worrying about car crashes.

True, there are many on low incomes who have no alternative to public transport (which is a reason it needs to be provided as a public good), but for many, it is considered an attractive option to vehicle use.

Incidentally, did I hear Simon Bridges saying something about PT investment having little impact on traffic congestion going forward in Auckland on question time today? (Greens questioning). I’ve gotta write an essay on Robert Aumann now.

An inferior good is, as you say, a lower quality good, typically consumed when income’s are lower. I have an average income and a car and travel by train feels to be a luxury. I do not have the stress of driving and worrying about car crashes.

True, there are many on low incomes who have no alternative to public transport (which is a reason it needs to be provided as a public good), but for many, it is considered an attractive option to vehicle use.

Incidentally, did I hear Simon Bridges saying something about PT investment having little impact on traffic congestion going forward in Auckland on question time today? (Greens questioning). I’ve gotta write an essay on Robert Aumann now.

any investment that “reduces” congestion will have no effect on levels of congestion, only on the length of the period of congestion, so a 2 1/2 hour peak might diminish to 2 hours, but you’re still stuffed during that period!

Pretty much right. However, providing congestion-free alternatives such as public transport on separate right-of-ways and protected cycle facilities means that more people can choose to opt out of congestion.

Bridges’ answer to the question suggests he doesn’t have the foggiest clue about how to measure congestion. Quite problematic given that Government’s policy platform is (apparently) focused on reduce congestion.

The old “we want to manage this thing that we don’t understand” trick.

Just a small quibble: an ‘inferior good’ in the economist’s sense is not necessarily a lower quality good. It’s just something that people tend to consume less of as they get richer. There’s a difference between the two statements.

Subsistence farmers, as they get better off, may consume less potatoes because they can afford more meat. That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with the quality of their potatoes.

And of course it doesn’t mean that all meat is a healthy diet.

Thanks for pointing that out, John.

This is one of those instances in which economists have chosen quite value-laden terms (“inferior” vs “normal”) for descriptive, value-free purposes.

It’s a really interesting question. Gut instinct would suggest that this is one of those questions that can’t be definitively answered, as there is no ‘average’ consumer of public transport. As one motor industry exec once said, “Our average customer has one tit and one ball”.

Also there are many, many factors that feed into this equation. But it can probably be answered for segments of the population based on gender, lifestyle, geographical location and purpose of travel. Perhaps it might be more helpful to reconsider the question as “What are the factors that affect a person’s propensity to consume a mode of transport?” and “All other things being equal, how will those propensities change if the person has more disposable income?”

The interesting bit is how the mode changes. You’d expect wealth to shift the quality of transport, but what this represents will depend on the individual’s circumstances. For example, in a suburban area you’d likely ditch the bus and buy a car if you were richer, whilst in an inner-city area you might ditch PT or even your car for taxis. And in both cases you might use long-distance rail and air travel more as you had more disposable income to travel.

Time is a factor as well as income. To get from my house to Wellington Zoo requires a long walk (maybe an hour) or a bus into town and then another bus to the zoo (plus waiting times between buses). If I could drive I’d take the car and be there in 10 minutes. It dawned on me one day that it was better to take a taxi than bother with buses. For an adult and two children the total cost was not much more than taking two buses, and the time saving was huge – especially important when children are tired after traipsing round the zoo for a couple of hours.

Absolutely true. And there are many situations where driving is the best option, but often in NZ cities that is simply because it is the only system we have invested in properly over the last half century. Whether your route can be efficiently served by a better bus system I don’t know, as I don’i know WGTN well enough, but in general terms the scale, density, and growth of Auckland means that the answer to that here is increasingly yes.

it may have changed, but 20 years ago when we lived there, Wellington was a much more taxi orientated city than Auckland, I see taxi stands around the place that are always empty