This is a guest post from reader Stephen Davis and was originally posted here.

New Zealanders are probably most familiar with the Resource Management Act (or “RMA” for short) as being about protecting the environment: when it’s discussed by politicians, it’s almost always either being decried as having environmental protections that are too onerous and stand in the way of progress, or alternatively being supported as the main defence of environmental health.

This perception isn’t wrong by any means – much of the RMA is about these protections of the environment in an ecological sense. Some aspects – fishing, minerals, conservation land – are handled separately, but most of the state’s regulations that aim to protect clean air, clean water, protecting the coastline, wetlands, native vegetation and wildlife habitats, and so on, come under the RMA.

But the RMA does far more than just what we normally think of as the “environment”, and this fact is probably less widely known. The RMA is also the main city and regional planning law, and planning traditionally covers social and economic matters as well as the purely ecological. This is done in an intriguing way: by creating a law focussed squarely on the “environment”, but then defining “environment” to include all manner of things outside the traditional understanding of that word. The RMA then defines its purpose as being to avoid “adverse effects” on “the environment”.

In the RMA, the definition of “environment” is broad, and includes:

- “people and communities”

- “social, economic, aesthetic, and cultural conditions”, and the big one:

- “amenity values”.

Keep that term “amenity values” in mind.

Ample Parking Day Or Night

New Zealand has a built form most similar to other Anglophone New World countries: Australia, Canada, and the United States of America. It’s long had a series of planning rules similar to those found in those countries: a focus on limiting density, spacing buildings out from the street and from neighbouring buildings, limiting the height of buildings and the shadows they cast, and almost universally, requiring that there be enough car parking provided on-site for the maximum number of visitors and residents the building is ever likely to have, assuming they all arrive alone in a self-driven car.

The other three countries, like New Zealand before the RMA, don’t require any sort of philosophical justification for this: it’s just there because policymakers and/or the voting public think it’s a desirable thing to achieve.

In New Zealand, however, the RMA requires any such regulation to be justified in terms of the “environment”. That idea of “amenity values” as being an environmental value is used to justify a large fraction of the planning rules that New Zealand has, including parking requirements.

This seems to be somewhat contradictory. Councils generally also have policies that are supposed to discourage driving, or at least promote alternatives to it, for reasons that are environmental in the normal sense: avoiding the air pollution and carbon emissions caused by petrol and diesel engines, the water pollution caused by oil and brake dust runoff, the environmental impacts of oil drilling to fuel the vehicles, and so on. Not to mention the other costs of driving that are not environmental in the traditional sense, but are in the RMA’s definition: the delays caused by traffic congestion, the deaths and injuries caused by driving, and the sheer financial costs to households of owning and running cars.

But there’s more to parking that just arguing about whether it’s a good “amenity”, or bad environmentally. There’s also the question of paying for it.

The High Cost Of Free Parking

Most parking spaces in New Zealand, on-street or off-street, are provided at no direct charge to the person using it. That doesn’t make them “free” in reality: carparks all sit on land, which isn’t free, and most of them cost money to build, which can be a serious expense in multi-storey structures.

Carparks at people’s homes are bundled into the purchase price or rent. Carparks at shops are bundled into the costs of the goods and services they sell. Carparks at workplaces are effectively a fringe benefit of working there, and so come out of the wages of workers. This is less of an issue if you’re paying one way or another, but this system has two natural consequences:

- You pay for parking whether you personally use it or not, which is a strong incentive to drive even if you otherwise wouldn’t have.

- You pay for parking even if it never gets used at all by anyone, which is purely wasteful.

This is an issue that’s been known for some time. The title of this article refers to the title of the book that is probably the best-known critique of free parking, by Donald Shoup, professor of urban planning at UCLA. You can see this interview with him conducted by Vox.

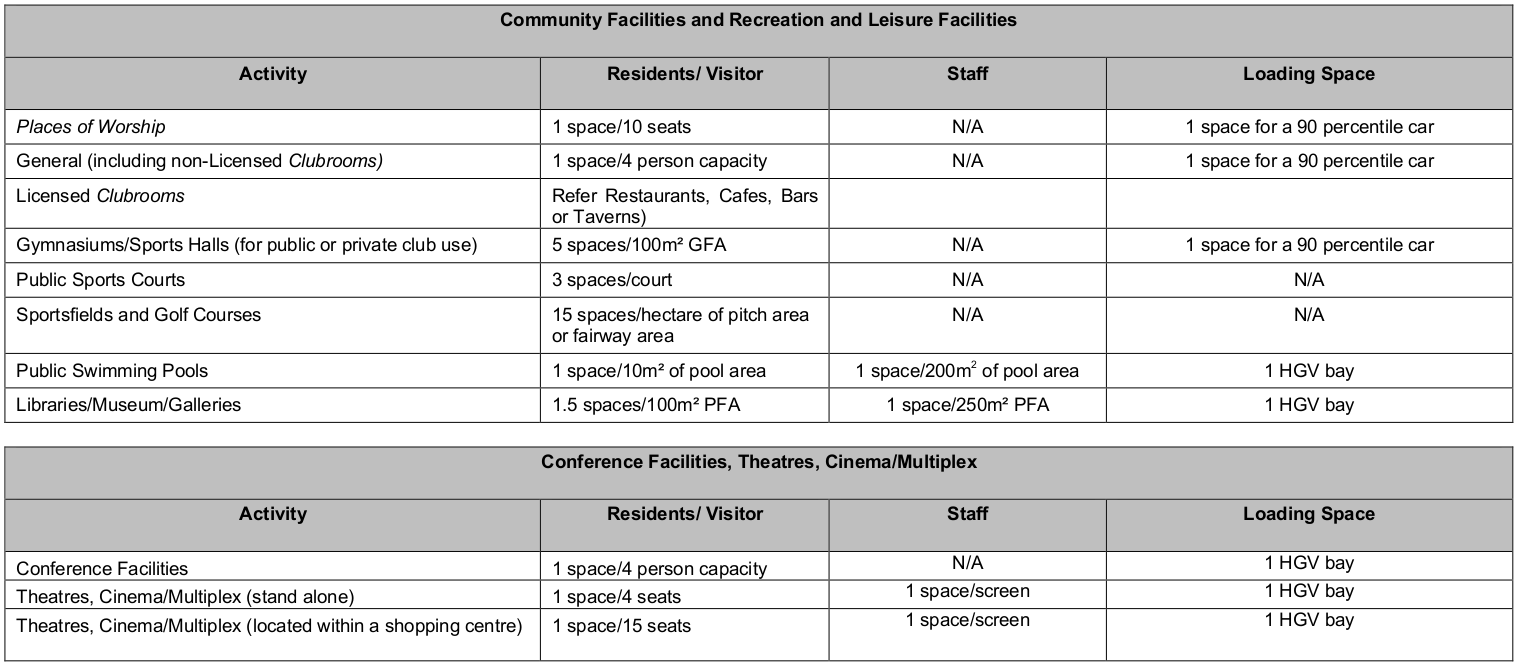

Our planning system doesn’t explicitly require that parking be free. It does, however, require a certain amount of it. Typically, for big developments, you hire a traffic engineer to do traffic studies and produce a report justifying how much parking you need. For small and medium-sized developments, you normally just literally look the numbers up in a large, incredibly detailed table in the District Plan.

One small part of the Tauranga City table of parking minimums

One small part of the Tauranga City table of parking minimums

Fail to provide “enough” parking, and your development will be turned down, even if you’re in a place with good alternatives like cycling or public transport, or even if there is simply ample alternative parking.

In general, these numbers are just copied from other nearby councils or come from professional traffic engineering guides. The original sources of the numbers is traffic studies: someone going out to an existing development with unrestricted parking, with a clipboard, at close to the busiest possible hour of the busiest day of the year, and counting how many cars are parked there. Then rounding up a bit. So the minimum amount of parking you must provide is slightly more than the maximum that might ever be used. Under these conditions, there’s pretty much no point ever charging for parking, since there’s never a shortage.

But Why Though

Why do we not just let developers decide how much parking to build, then live with the consequences of building too much or too little? Remember that this scheme is justified in terms of “amenity values”. When a development is proposed, there’s a benefit for visitors and residents in it to always being able to get a parking space, gratis. But that isn’t the theoretical reason we’re doing this. The “amenity” is to everyone else nearby. If our development doesn’t provide enough parking, people might park on the street (the horror!), and if enough people did this, all the on-street parking would be used up, and then people living in or visiting neighbouring homes and businesses wouldn’t be able to park on the street1.

So, the terrible “environmental” effect we’re avoiding is… people using on-street parking spaces. Which are only there in the first place to be parked in! In the worst case, some people might have to park a little farther away, or need to put in their own on-site parking, or the council might need to manage on-street parking by putting in time limits, meters, or a system of residential permits.

This imposes vast costs on new developments, which are passed on to their residents, customers, and employees, whether or not they drive. It’s particularly acute in higher-density developments. First, because higher density developments tend to be in places with better alternatives, like walking and public transport, so fewer people want to use the spaces in the first place. Second, if parking spaces need to be built in a basement or multi-storey structure, they can cost $30,000-$50,000 to build. In a day and age when the cost of housing is one of our biggest political and social issues, is this a smart policy?

Who Will Rid Me Of These Troublesome District Plan Requirements?

This is not a new issue. You can see in this video the current Associate Minister of Transport, Julie Anne Genter, then a professional transport planner, arguing against parking minimums nearly ten years ago. The Minister himself agrees. In opposition, both pushed during negotiations on RMA reform to abolish parking minimums. So why hasn’t it happened?

The RMA is a political football and hugely contentious. It’s been amended, on average, more than once per year since it was first enacted in 1991. But never have the core values been touched: the definition of “environment”, or the “matters of national importance” that are supposed to be central to decision-making. In part, it’s just been too hard for a coalition government to agree on lofty philosophical issues. The previous National government could never get its support partners ACT and the Māori Party to agree, and the current Labour government is likely to have similar problems with its support partners the Greens and New Zealand First. Amendments have tended to be either extremely ad-hoc about specific issues, or generic changes to procedures, hoping that councils will do the hard work.

Councils could do the hard work, in principle. The RMA does not require parking minimums, it merely allows them. Auckland and Wellington have both abolished parking minimums in their CBDs and in some suburban town centres. But even the most courageous councils tend to be more conservative than central government. With low voter turnout and small constituencies, councillors are more worried about criticism from a vocal minority who want to retain free parking than lofty but abstract ideas of economic efficiency or fairness. They’ve had decades to act, and haven’t.

Maybe someday we will get a more comprehensive reform of our planning system. I suspect it’s still many years away. But in the case of parking, I think there is an alternative to legislative reform that doesn’t rely on councils, and can happen far more quickly.

Setting The Standard

Councils adopt parking minimums through having rules in their district plans. Comply with the rules and you are fine. If you don’t provide enough parking, you need to apply for resource consent, which typically (though not always) will be declined. As seen above, this is a series of numerical tables, providing a standard which needs to be met, at which point you will be judged to have avoided an adverse effect on the environment.

The RMA provides that councils can set standards for the environment. It also provides that the central government can set a standard, if it’s seen as desirable for the standard to be uniform across the country. It can choose whether or not councils can provide a higher or lower standard. There is a process that has to be followed, with a series of public hearings and technical reports, but ultimately it’s up to the Minister for the Environment and Cabinet to decide what to enact.

This is done with an aptly named National Environmental Standard or “NES”. This is one of three main ways that the central government can issue directions to councils without legislative change. The others are:

- National Policy Statements, which the previous National government created several of. The downside is that they don’t have direct effect: they are general policies that local councils are obliged to follow, but they are only obliged to follow their own interpretation of them.

- National Planning Standards, which were only introduced last year and haven’t seen much use yet.

Any one could be a useful tool. I think the NES is the most apt, however. It has direct effect, and isn’t subject to being “interpreted” into nothing by councils. It’s also intended for crunchy, technical, numerical standards, which is what the parking system currently is.

Under the NZ planning system homes for cars are more important than homes for people

— Francis McRae (@FrankMcRae) September 5, 2018

What Would A National Environmental Standard On Parking Look Like?

An NES can set essentially any rules that a District Plan could. A NES could, in principle, reproduce parking requirements similar to current ones, but simply standardised across the country. Obviously, this would be a bad idea.

But it could instead provide that, in urban areas, the minimum amount of parking required is zero. Councils would be able to set a maximum amount of parking, but they would not be free to set the minimum at anything other than zero.

This may seem a little cute: using a method intended to set a standard in order to abolish the idea that there should be a standard. But it’s not without precedent. There is a NES on “telecommunications facilities” for example, which among many other things is intended as a measure to abolish council powers to restrict the siting of telecoms boxes on footpaths.

It’s also possible we might want to retain some standards on parking: requiring loading spaces for large developments, parking for bicycles (which Auckland Council does), and various geometric design standards for parking where developers do voluntarily choose to build it, for example2. We might also possibly want to keep parking requirements in rural areas, where significant amounts of on-street parking on 80 or 100km/h roads tends to be a safety issue, and there generally is little or no alternative to driving.

One way or another, though, a National Environmental Standard could be a quick, easy way of abolishing the blight of parking minimums wasting land in our cities, and reducing the cost of parking oversupply on residents and businesses.

Notes

- This seems to be incoherent as well. Why are the occupants of existing buildings entitled to free on-street parking at public expense, but the newcomers aren’t? However, this seeming unfairness isn’t really relevant to the main point. ↩

- You may be thinking of disability parking as well: this is already handled through the building code, which does not require that there be parking in the first place, but does require a certain proportion of any parking that is provided to be disabled spaces. ↩

Processing...

Processing...

I know this is off topic but following the environment thread and parking. On RNZ is an article about banning copper brakes. copper is very ecotoxic ( ANZECC 95% trigger value is ~1.6 ppb and a new revision of the tv lowers it to be 1 ppb). Will abolishing parking minimums have other unintended consequences on the environment?

What sort of unintended consequences are you thinking of?

Less parking might encourage people to drive less (either use PT or walking/cycling). Then this might reduce stormwater pollution, green house gas migration). The alternative of course is that people drive more looking for the elusive parking spot. I was wondering if there was any research on how less parking influence people decision to drive and how that impacts on other environmental matrices. Are we at stage to say each carpark impacts on WQ by this amount or increases GH gases by x%. If we could then I feel we will be encompassing the environment assessment envisioned by the RMA.

Thanks Stephen, such an important topic.

I had a home business owner complain to me about the proposed rating of home businesses as if they are normal businesses the other day. She believes her construction business doesn’t add any costs to the council. In reality, the company often uses three off-street parks for trailer and utes, in addition to their having a double vehicle crossing and no kerbside parking in front of their property. She – like many – doesn’t see kerbside space – and vehicle crossings instead of safe footpath – as a public amenity her company is using.

The upshot for me, as someone who cycles with children, is that neither the footpath nor the road ends up being safe for cycling. There’s already the road given to cars, the kerbside space should be given to bikes.

You’re welcome, and thanks for taking the time to comment.

The case against parking minimums doesn’t really depend on whether or not we have on-street parking, although the outcome is different. In most of NZ, the explicit “problem” that parking minimums were invented to prevent is not even close to existing: there’s vast amount of on-street parking that regularly goes unused. It seems particularly silly to require people to build new parking to avoid overusing the on-street parking… when no-one uses the on-street parking.

But if we abolished all on-street parking, and parking minimums, people will still drive and park. I think one of the most likely outcomes would be that individual business would stop providing parking, and a proliferation of private paid parking lots would spring up: this is a very common setup in more car-oriented parts of Japan, for example, which largely does not have on-street parking (simply due to having streets too narrow for it) and has relatively low parking minimums.

There’s also the effect that the provision of parking is the strongest determinant of parking demand. Having to provide offstreet parking shifts all the buildings and amenities further apart, so there is more need to drive. Having offstreet parking provided means more people don’t look to alternatives and it entrenches their car dependency.

A Japanese system would required cars to register to an address that has its own parking (either in home, or rental parking building like Wilson parking).

That helps to make sure people can’t use the kerbside parking as permanent parking.

Does this work to keep a cap on the number of cars per household? The households around here with more vehicles than on-site spaces is large. But of course, we’d be relying on enforcement of the permeability requirements, which are completely ignored as it is.

That is indeed the problem you currently get with any development with less than 2 spaces per house. Another wall of parked cars on the street. If on-street parking is free, then only the suckers will pay to rent (or build?) an off-street car park.

And what do we read in that Twitter feed about cohaus? “…but the experts are concerned that if they got cars later they might park them in the street”.

What do do? Charge money for on-street car parks? Turn down developments? The choice says a lot about what’s valued by society.

And the consequences of this value judgment is that residents are stuck on the motorway and clogging up the rat runs as they commute from their car-dependent suburbs on the outskirts, prevented from living an active lifestyle in NIMBY Grey Lynn. So this value judgment results in us all breathing the fumes and being subject to the added traffic danger.

I imagine time limiting on street parking would be reasonably effective. Still means it can be used as visitor parking but isn’t much use for the regular storage of a car.

Yes, but charging would cover the costs of enforcement, which otherwise they do at such a low rate that people prefer to pay the costs of a fine.

I think it’s worth pointing out that the Japanese proof-of-parking system only applies in major cities, not in small towns or the countryside, and Japanese major cities tend to have little or no on-street parking anyway.

It’s conceptually a much better way of viewing parking, but I don’t think the actual time-consuming bureaucracy of it is necessary, if you have adequate enforcement, and if you don’t have adequate enforcement of illegal parking, there ends up being a huge incentive to corrupt or defraud the proof-of-parking system.

Correct Stephen. Better that Auckland take the JP concept of proof-of-parking rather than apply the actual system itself. Aucklanders must accept that onstreet parking and car parking in general outside of the space in their own driveway, is a privilege and not a right.

How depressing to read the link to “your development will be turned down” which is about the Council planner recommending the Cohaus development is turned down because it doesn’t have enough car parks.

Unbelievable! When I was learning about the Cohaus development a while ago, I was told the Council planner had said 0.5 carparks per residence was fine, and the design had been developed on this basis. What process is the Council planner using? Is it called:

“Lead the progressives on a wild goose chase to waste their time and then hit them with the parking stick at the end so they won’t try it again”? Or

“We’ll appear to be progressive but let’s make them have to notify it to the owners of over 100 properties in order to harness that regressive NIMBY force, and then we’ll appear justified in turning it down”?

This isn’t how I want to see my Council behaving.

Truly stupid isn’t it.

Does anyone actually believe that planning has an overall positive impact on a city? If they got rid of all planning completely (saving the council and anyone who ever tries to build anything a ton of money), would we really end up with a worse city? I highly doubt it.

I watched on TV the other night in the states where they had an area dedicated to people building tiny houses. It would be a really good idea to allow people to own a minimal residence (a roof over their head) for minimal money. Something like cohaus with shared spaces, etc. Can you imagine how much red tape that would need to go through here? The planners wouldn’t allow it, and even if they did you would need an architect etc to draw up plans, 10 or more building inspections, etc. The red tape would cost more than the tiny house. Its why we end up building Mc Mansions everywhere – the red tape is effectively a fixed cost that makes small houses not viable.

I sure hope Twyford fixes this mess. If we want affordable housing, the council and MBIE need to be stripped of their powers ASAP (and not just when the government wants to build something).

The two major negative consequences I’d predict from removing all planning rules would be 1) development happening where there is inadequate infrastructure to support it and 2) residential development happening in industrial areas.

1 is a problem because infrastructure owners wouldn’t be able to plan ahead for where to improve their networks. This could be solved if they can charge developers the full marginal cost of infrastructure improvements, however I can still see it not working well for PT.

2 is a problem because of reverse sensitivity. Residents, having got a cheap house because its in an industrial area, would turn around and complain about the noise, odours, truck traffic etc. They’d lobby local and central government, who’d eventually introduce something like planning rules again. Meanwhile the industrial area would lose some or all of the agglomeration benefits of locating related businesses near one another.

That said, I think we could do away with very nearly all planning rules and the positives would outweigh the negatives.

I guess planning rules are required for things that genuinely affect your immediate neighbours – some kind of zoning of industrial areas, some kind of height to boundary, etc. Although maybe that could be at a government level rather than council (government defines the zones, council chooses their location).

I have a relative that subdivided his section recently. The planners pretended to be supportive (“we are keen to help people provide more housing”), but in the end the process was an absolute nightmare costing hundreds of thousands of dollars and much more of his time than he anticipated. Why does it need to be anything more than informing the council of the new boundary co-ordinates, total cost of ~$2000 for a surveyor?

Why did it end up costing so much? Sewage or stormwater infrastructure?

There are lots of charges associated with subdividing : development contributions etc

Our society is being held back by the astronomical costs of providing car storage at both ends of nearly every possibly envisaged journey. The provision of this storage space dilutes the availability of land for production of wealth, space for housing, and social amenity. This dilution also extends the distance, and therefore the efficiency of transport between these functions of our life. Our big suburban shopping centres show the absolute stupidity of this, where just to get between two shops in the same centre, it is almost always easier to get back into the car and drive to yet another of those mandated car parks.

Yes. Now I thought this was an interesting tidbit from the AA’s submission to the Productivity Commission about a Low Emissions Economy:

“On average, 30% of the cars in congested downtown traffic are cruising for parking. In a year, cruising for parking creates 366,000 excess vehicle miles of travel and 325 tons of CO2”

This is of course a direct quote from Donald Shoup. The AA is using the figures to call for smart pricing technology for parking. They also call for removal of street parking or peak period clearways. Isn’t that interesting? I was about to cancel my AA membership, which is a waste of money for someon who drives so rarely. Maybe I’ll reconsider… although I’m going to ask them what their official stance on adopting Vision Zero is before I decide.

One thing worth noting is the AA now do Roadside Rescue for e-bikes! Bonus

“Why are the occupants of existing buildings entitled to free on-street parking at public expense, but the newcomers aren’t?”

This is enshrined solidly in the parking strategy, too. I can see the point if it is overtly a transitional policy to give people time to adapt, but that’s not what we’ve got. There needs to be a policy like, “road space is public space, and over the next ten years, Auckland will work towards removing all free kerbside parking and converting it to full public use – through widening footpaths, adding cycle lanes, adding gardens and trees and seats to improve the experience of walking and cycling (all of which have high benefit cost ratios through improved public health), to bus lanes, and also providing some parking priced to cover the full cost of each park, including the land cost and the effects from the traffic each park induces.”

looking at aerial images of Manukau or Albany ‘city centres’ or any other big box retail development highlights the huge amount of space/resources required for car storage. Absolutely absurd that these are ‘required’ and mandated.

Agree. If they are going to have such rules, surely it has to apply to all modes of transport? For a residential house: you have to provide a covered secure bike rack for at least 10 bikes, an umbrella stand for at least 10 umbrellas, etc. It seems extraordinary that a council can use the RMA to favour cars as a form of transport to ‘improve our environment’.

Apparently we still need minimum parking requirements for bikes. Can you believe that after limiting parking in the CBD for 30 years they brought back minimum parking rules only this time for bikes. I had to try and justify a dispensation from bike parking requirements in a building in the CBD that has no basement to put them in. AT seemed to think it was ok to require that some of the most expensive ground floor area in NZ is used as a bike parking room.

Yes – the council always knows more about what you need than you do!

It just amazes me that people at AT think it is acceptable to require bike parking instead of retail activities in some of the most expensive real estate in NZ. I guess it costs them nothing. Shame they can’t see beyond their own narrow viewpoint.

How does it weigh up across the city, miffy?

The thing I have learned about AT is that if they are spending money then they do a benefit cost analysis, then they trim costs to the bone and leave no corner uncut. But when the get a chance to make someone else spend on something they want then they ask for a gold watch every time.

I worked on one job where AT had widened a road and built a new vehicle crossing to their ‘standards’ and before it had been used the owner applied for a resource consent for an activity that generated less traffic and AT demanded it be rebuilt and upgraded as it wasn’t to their standards. They basically have two sets of standards, one cheap set for themselves and one they demand of others. The lesson is never ever trust them, get everything in writing and make sure you bring a lawyer.

Ha! Yes.

What Miffy says here applies to stormwater infrastructure on Waiheke. In essence, there isn’t any infrastructure, except a total mess, being whatever happens at the road edges.

When doing road works, AT will find an unused section and direct road run-off onto it, completely unmitigated, via a short pipe; rendering the section un-developable and anyone downhill of that at risk of being flooded. (To be fair, they inherited a fair bit of this, but it looks like it still happens).

Whereas, if a developer wants to discharge any stormwater to the road (and there’s nowhere else for most of it to go, given the clay subsoils, steep sites and need to discharge wastewater to ground), then AT want road upgrades performed over a wide radius from the site. This applies even though the discharge will have to first go through detention tanks and be slowly released at or below pre-development levels.

I guess that’s efficient use of taxpayers’ funds, to dump water on some private landowners without mitigation, and refuse to accept water from other private landowners without requiring an expensive favour of their choice in return. But there’s no accountability: They are the ‘asset owner’ and no-one can discharge to ‘their’ road without their permission. They are treated as a private landowner, not as a public body. Thus they set their own rules. And where they haven’t got any written down that apply, they just look for an invented gold-plated outcome, at the developer’s expense.

I just had a conversation this morning with an inner west resident (in her 50’s) who works in town, and visits clients around the cbd. She usually chooses to walk, has been turned off the buses by the wait time for the Outer Link at Victoria Park, and wishes she could cycle. The reason she doesn’t? To my surprise, it wasn’t safety, it was that she doesn’t feel there are places to chain her bike up.

So what do you think the solution is for the site you are referring to, miffy? Luckily not all buildings do have basement carparks – I mean, those are a huge outlay of resources. There often isn’t footpath space to dedicate to bike parks. Yet given the public health benefits of cycling, and its fantastic business case, these bike parks need to be provided.

Is it some bike corrals on the road space that would have worked in the location you’re referring to?

This is a huge obstacle to riding in my current home of Tauranga. The city has a reasonable wide and continuous network of bike lanes, albeit many are just paint. But there’s often zero ability to park your bike at the other end. I can ride nearly ten k’s from my house to the mall at Bayfair without going on a main road, but I can’t stop when I get there. (I tried chaining my bike to the shopping trolley return, the only thing available, and 90 seconds after walking into the mall, someone was on the PA saying that whoever had parked that bike had to move it).

Tauranga has just recently adopted bike parking requirements. I wouldn’t say that they should be required generally, or in residences, but if you are going to choose to provide parking (or if parking minimums are retained), then you should have to provide bike parking too.

Doesn’t Bayfair have bike parking around the back (Farm St) entrance? There’s a stand with free to use bike tools and I thought there were bike parks near that.

I arrived off the Matapihi Road cycleway, which goes under an underpass then dumps you straight into the carpark. I toured the whole carpark on the Matapihi Road side and didn’t see any bike parking.

There may be bike parking on the other side, but A. how would you know that, unless you’d already visited by some other means of transport, and B. I don’t know how you’d get to it without riding along Girven Road, a terrifying and risky endeavour.

Indeed. But you must know by now that Tauranga hates any mode of transport that isn’t a privately owned vehicle, preferably with only a single occupant.

I don’t understand why the city is following the development model that has already failed for Auckland. More motorways and urban sprawl of standalone McMansions built on land that’ll soon be inundated by rising sea levels.

Tauranga is definitely trying to be 1990s Auckland, and rapidly “succeeding” at that.

If bike parking is needed then AT should provide it just as they provide all of the visitor parking for cars.

I am not a lawyer but I wonder would it be possible to express parking requirements on a performance/functional basis rather than a geographic/zoning basis? That is, instead of saying, you are in zone X so you must have Y parking spaces, say you are within Z hundred metres of an operating mass transit system so may have no more than Y/2 spaces, or you are beyond Z hindred metres and so must have the full Y spaces.

Why mandate it? Surely if your business or lifestyle requires parking provisions, you have the choice as to where to locate, and can choose a premises that includes your vehicle storage requirements. I think we need to start now with a sinking lid on mandated parking provisions, and the supply of kerbside parking coupled with the rigourous application of the council pricing of their controlled spaces to acheive the maximum of 85% occupancy.

To a degree, this is indirectly how the current system functions: in Auckland parking requirements do not apply in some zones, particularly denser residential zones or mixed-use commercial areas. The system used to decide where to apply those zones, in turn, mostly looks at distance from mass transit and town centres.

However, there’s a lot of exceptions to that general rule, and I think your system of judging distance to transit directly would be an improvement. For example there area areas that are zoned single house for “character” reasons, rather than because they don’t have public transport access. Even if that were justified, which it isn’t. it doesn’t follow that the parking requirements must change for “character” reasons as well: the logic of not needing parking because you’re close to transit hasn’t changed just because it’s a “character” area.

The other advantage of mandating distance or accessibility levels is that as soon as the physical situation changes e.g. completing a new rail line and stations, the parking rules change with it.

Why have parking standards at all (minimum or maximum). Let private land owners provide what they want…

This paper refers to research presented at a 2016 TRB conference by “Chris McCahill of the State Smart Transportation Initiative and a trio of University of Connecticut scholars” https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2016/01/the-strongest-case-yet-that-excessive-parking-causes-more-driving/423663/

“they suggest that cities consider policies designed to limit parking to its strictest natural demand. These include the elimination of minimum parking requirements, the use of maximum parking requirements in some places, and the implementation of market-based pricing. What’s at stake, they conclude, is nothing less than the health of the city.”

It’s funny that Council is prepared to ignore the research on how parking minimums lead to more driving, less active mode share and lower public health. At some point, will there not be a case taken against them for ignoring the research on the same sort of basis as cases were taken against organisations ignoring the research on how smoking affects public health? The Healthy Streets research would show this planning decision is causing ill health and premature death – does that not weigh on the reporting Council planner’s conscience?

Stephen — thank you so much for taking the time to write this article covering off why and how we might improve the way we manage the supply of parking. I’ve been working in this area for around a decade, often with Julie-Anne, during which time we’ve had to draw most of the evidence from overseas. It’s really useful to have these arguments reframed in a New Zealand planning context, hopefully in a way that local planners and RMA lawyers can grapple with. The latter are, in my experience, one of the major obstacles to reform, long with oligopolistic retailers, NIMBYs, and the latter’s elected representatives.

Thank you, both for your comments, and the work you’ve done.

From a planning point of view I think the most interesting point is how thinly justified parking minimums are within the point of view of the RMA itself. In overseas jurisdictions, parking minimums and planning regulations in general are just a local law, and that’s the end of it.

But under the RMA, rules have to be justified in terms of avoiding, remedying, or mitigating an adverse effect on the “environment”. I’m actually slightly too generous to our District Plans in saying that parking minimums are justified by reference to “amenity values” – usually, they’re not explicitly justified by anything at all, and sometimes they’re justified solely in terms of safety, which doesn’t really pass the laugh test.

Auckland’s plan, both in its text and in the statutory section 32 report that has to be prepared on it spend a couple of sentences justifying parking minimums – while spending pages and pages justifying the small number of places where parking *maximums* are imposed. In general, the main adverse “effects” that parking minimums are supposed to avoid are localised congestion (from people cruising for parks, presumably), and greater amounts of illegal parking.

However, there’s no comparison with other (probably more effective) means of addressing those issues, like market-clearing pricing and parking enforcement, and also no analysis checking that the “solution” doesn’t cause more problems than it solves. Which it almost certainly does, so far as parking minimums encourage more driving.

This state of affairs makes far more sense when you think about how much lawyers drive the planning process: big car-oriented retailers will spend lots of money challenging parking maximums and restrictions on out-of-centre retail, so lots of conceptual work needs to be done making sure the case for maximums is robust. While no-one usually hires lawyers to challenge parking minimums in general, rather, just applying for an exemption for themselves at consent time. So there’s little need to courtroom-proof your parking minimum rules.

that’s because “accepted wisdom” > “actual evidence”

I have also often wondered what the ‘resource management’ issue is that parking minima purported to address, and as you say its pretty thin, and a long the lines of “Someone is parking on myyy street!??!” .

The reason being is also i think, close to what you and Stu surmise, in that like jaywalking, its a successful claiming of public space for particular private ends, in this case, initially vehicle manufactures and oil barons, but now maintained by oligolistic destination retail providers whose key point of difference from the traditional main street, is lashes of (“free”) parking.

Your analysis of the weight of justification given to the limited parking maxima in the AUP (vs marking mins that apply everywhere else) also exactly reflects the legal effort put in by large parking providers (ie suburban shopping malls and supermarkets) to avoid having what they see as a competitive advantage undermined by a change in both the overall transport system (a longer term game but one worth poutting off as long as possible) and a reduced cost of entry to competitors (who would no longer need to have a car park x2 the floor area of the their store).

The other argument was that ‘freeriders’ may even use the uncontrolled parking provided and therefore would, wait for it… impose a cost on the owners of these carparks, as they might need to manage them

sausagechops

It is an interesting situation regarding the malls and other big box retailers who have myriads of parking. I have submitted regarding the Carbon Zero Bill that if you run an industry/business that causes greenhouse emissions then you should pay for it. If it is good enough for the agricultural sector then it should also apply to the retail industry and others who offer parking. Could the mechanism be a parking tax?

Great article Stephen. Fantastic that you’ve framed it in the context of NZ laws too.

One the that has always confused me is why increased local demand for car parking is an adverse effect. Parking is a service: for any other service, increased local demand is a positive effect. A local hairdresser wouldn’t oppose development on the basis of needing to charge more for haircuts!

I also agree with mfwic that cycle parking minimums are bs. Cycle parks should be like loading bays or disabled bays 1 for every x many carparks or cash in lieu for AT to install them on street nearby.

Yeah, the justifications made for parking minimums all rely completely on the idea that we don’t treat parking as a commercial service in its own right. Which is because thanks to parking minimums, there’s such a glut of parking that most of the time it’s not worth charging for.

The irony is, if we did, I think it’s possible that some of the arguments about parking could become inadmissible, as the RMA requires councils to ignore the effects of “trade competition”.

Imagine a bar that offers free bar snacks, as a loss-leader, in the hopes that people in the area will be more likely to buy extra drinks while they’re enjoying their snacks. Another bar opens nearby that doesn’t do this, and uses the savings to make the drinks slightly cheaper. Suddenly the first bar has loads of people coming in, loading up on snacks, then moving on to the new bar for drinks.

Under the parking-minimum logic, this is an “adverse effect”. The first bar has to respond by either charging for snacks themselves, or instituting a system where customers need to show that they’ve bought a drink to qualify for the free snacks. If they don’t, they’re going to lose money giving away free snacks. Regardless of what they choose, there’s a cost to administer the new system – training staff, adding options to the till. Maybe the new snacks aren’t self-serve.

This isn’t the way the first bar wanted to operate, so it faces a cost to switch to its second-best option. But these costs are just the result of competition, so under the RMA it’s not something we can consider.

Brilliant article,

I read Shoup’s book, very interesting reading about the devastation parking requirements a causing to cities.

IMHO, the RMA should be amended to protect only the physical environment (waterways, native bush etc.)

There have been numerous developments in the Auckland , where a developer wants to build a building of say 40 apartments & provide 20 parks. Council then rejects the proposal because approving the development will change the fabric of the community. Essentially the community is currently a suburban one in which free market pressures are essentially pushing for it to become more urbanised. Further the council also uses the basis of not enough car parks provided as the justification for rejection. Council then tries to get the developer to provide the 60 carparks required. The developer rejects this as he can now only build 30 apartments, as they are required to provide the 40 extra carparks, of limited value. The numbers just don’t add up. The developer then shrugs his shoulders & figures they will sit on there hands for another 20 years & see what happens. No apartments get built, the housing crisis worsens.

That does seem to be the problem. Out of interest, are any of the developments you’ve seen recent ones, since the AUP? I know someone writing about some car-dependent developments Council consented, despite their not fitting the zone description given in the AUP (in the slightest) nor meeting the permeability and coverage rules. More examples of progressive developments that were refused might help with that article.

Any thoughts on the effect banning mpr’s would have on rural areas/smaller towns (I.e. the .majority of no districts)? Shoup’s work is mainly based in mega-metropolii like LA. He says that it only applies in larger cities where land is more valuable than a certain threshold. Do you think MPRs still have any value in the Greymouths, Te Pukes and Gores of the world?

In places like Greymouth I think parking minimums are probably even less justifiable than they are in Auckland. New Zealand’s existing small towns tend to have overly wide streets with a huge existing unused surplus of unmetered, unlimited on-street parking.

If you were building a town of that size from scratch, you’d probably be slightly more thoughtful about it, but small towns are only barely growing or even shrinking, and already have massively more parking than they’ll ever need. Stick up a bunch of P60 signs on the main drag and you’re done, really: you don’t even need to charge for street parking.

I think it’s also worth pointing out that removing the power of councils to require on-site parking doesn’t mean that no-one will provide on-site parking, let alone that parking will suddenly become unavailable. In all but the tiniest of hamlets, if there’s ever a shortage of parking somewhere it will become commercially viable for a private operator to set up a paid parking lot.

If we abolish parking minima, it’s probably also worthwhile looking at the consenting process for standalone parking lots, which I’d expect to become more common. In Auckland’s Unitary Plan any standalone parking is a completely Discretionary activity. I think that’s probably too onerous, and small surface lots (under 50 spaces, say?) should be easier to get consents for, at least in suburban areas with nothing out-of-the-ordinary going on.

Completely rural areas are probably a different story, where there’s guaranteed to be enough space for parking on-site at every activity, and parking minimums are probably more a question of safe design than any real fear that anyone will build a popular destination with no parking.

Surface parking lots create poor urban form, Stephen. In real terms, this means areas of the city which don’t have passive surveillance and don’t have enough activity and green infrastructure to make them liveable. If you want to allow the market to respond to the situation of demand for parking, then you need to understand the real “parking demand”, which is the occupancy rate under market conditions. We don’t have market conditions, and we’re so far away from being able to impose market conditions, that the idea of allowing new surface parking lots is a complete joke.

As our cities intensify, that development needs to happen with sustainable transport modes, not with car dependent planning. New surface carparks are not part of that mix. Indeed, we need to repurpose the many existing ones.

Not discretionary? You’ve got to be joking. The existing ones need to be taxed to cover the costs they are imposing on society, and there needs to be a ban on new ones. Private cars are not part of a responsible way forward as regards climate, environment and social issues.

“If we abolish parking minima”, I said. Abolishing parking minimums doesn’t immediately remove existing parking, and doesn’t even necessarily stop new developments choosing to provide new parking.

Encouraging developers not to provide on-site parking, or to redevelop or remove existing parking means one of two things:

* leaping instantly into a 0% mode share for cars, which is not going to happen any time soon outside of the Wellington and Auckland CBDs, which already have considerable limits on parking

* there being some other parking available in the area, on-street or standalone.

That off-site parking may be new parking lots, or far more likely, may be repurposed accessory parking, but either way under the current Auckland Unitary Plan it needs resource consent: whereas retaining it as accessory parking (or even building new accessory parking) doesn’t.

In that context, banning standalone parking lots doesn’t mean less surface carparking – it means *more*.

In a political sense, I’m also a believer in incrementalism. At the moment, having massive amounts of free parking is essentially compulsory. It’s probably an easier sell to make parking genuinely optional and market-priced, rather than leaping straight into banning it.

Once you’ve made the first change, you see what happens, learn from that, then start looking at where to go next.

I also like small steps. I guess I don’t like the idea of making it easier to build any carparks by changing them from Discretionary.

In Auckland, one small appropriate step is to add a carpark tax (to capture all the costs involved with the land, resources and amenity being used by the car park user). Again, this can be small to start, but the intention to increase it over time should be overt. And all kerbside parking and other Council owned parking should be dynamically priced, again rising over time.

Of course, this is more progressive than the Parking Strategy. But the problem we have is that those parts of the Parking Strategy that are good – eg adding time restrictions, then pricing, then increased pricing, etc, to ensure 85% occupancy isn’t exceeded in the peak, is being ignored by AT.

The obvious small first steps available aren’t being used. And it’s leaving us exactly with the Shoup-described situation of cars driving around and around looking for parks, wasting fuel, and endangering vulnerable road users.

Cheers Stephen, that’s insightful. I’m kind of just playing devil’s advocate. I wonder if part of the reason changes at a national level (RMA) have been difficult is because it’s hard to get something that is applicable to everywhere in the country, which covers a massive range of very different situations, from Auckland CBD to some paddock an hour out of Greymouth.

The Auckland CBD to a paddock outside Greymouth is a big leap, but it’s not really a bigger leap than from the Auckland CBD to a paddock outside Waiuku. Those two already share a Unitary Plan.

An NES on parking doesn’t have to apply nationally, and it doesn’t even have to have rules that are uniform *within* council areas. But while it’ll have the biggest impact in the main centres, that doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t apply to smaller towns as well. So I think it should simply apply nationally.

A nationally set parking minimum of zero would work pretty well IMHO. Then just require a traffic impact assessment for developments over a certain size. That way the effects of not providing car parking are actually assessed against their effects on traffic, not an arbitrary minimum.

Good to see you here by the way Chris.

Great article Stephen. May I suggest that as well as removing minimum parking requirments, it also be mandated that a business must pass on the costs of providing parking to those who benefit from it, and may not, either directly or indirectly, to those who don’t.. i.e. If I happen to take public transport or walk to the mall or supermarket, I should not be paying for a carpark via the cost of the goods I buy there.

Essentially this would require some form of parking fees to cover both the cost of providing the carparking and the overheads in administering this. There is nothing stopping the business making additional money from the parking if they choose to charge a bit more.

The benefit should be that the cost of goods in these businesses should be less because the parking charges are no longer included. It should also have an effect on the induced demand for parking and on the nearby roads as customers choose alternative options to get there.

That sounds needlessly complex and difficult for the government to regulate. I think if retailers weren’t required to provide parking, plenty wouldn’t, and they’d be able to compete better by offering lower prices as a result. Retailers providing “free” parking wouldn’t be able to compete in desirable urban areas, and they’d be relegated to locations inaccessible except by car.

That said, I think we really don’t know quite what the post-parking-minimum world will look like. Best to do just keep our minds and eyes open to whatever trends take root, then respond once we know what the future brings.

I agree, Martin. We need a car park tax. Trying to exercise my consumer power by only choosing retailers that don’t provide carparks is quite restricting in Auckland. Also, how do you get around the fact that AT is providing carparks for free, so we’re all paying for it in our rates?

Central London went in very short period of time in the 1960’s from mandating the number of car parks for new developments to in 1975? heavily taxing all off street carparks.

Removing parking minimums would work with smaller retailers who would do away with parking if this wasn’t required. However when would this have any effect on the monuments to the private vehicle I.e. the large shopping malls? I suspect that given the token effort taken by most mall owners/operators to provide better alternative options, I don’t think there would be much change unless it was mandated in some form.

New World Victoria Park now has made some of it’s car parks into weekly rentals. Obviously the return from this is greater then their contribution to their shops turnover. No doubt the provision of these car parks was part of the original consent, but the original rationale is now proven to be obselete. One wonders what descisions the developers would have made had provision of the numbers of car parks not been mandated.

If the provision of car parking was subjected to a sinking lid then I am sure that more and more parks would be repurposed into more productive land use, and the owners of the remaining car parks would be seeking, a better return.

.

Good post thanks.